Phil Ramone

Above: Phil Ramone holds Ray Charles' 'Genius Loves Company' awards at the 47th annual Grammys.

February 2005Interview by Matt Howe / Barbra Archives

Phil Ramone is one of the most respected and talented producers in the music business. A 12-time Grammy winner, Ramone is also a true “techie.” He has been involved in many pioneering technical innovations in the music industry, including the compact disk, fiber optics, and Surround Sound.

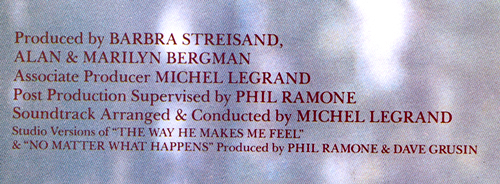

Musically, Ramone has worked with some of the best talents: Elton John, Frank Sinatra, Liza Minnelli, Karen Carpenter, Ray Charles, Simon & Garfunkel, and many more.Phil Ramone also includes Barbra Streisand on his resume. He did the sound at the Sheep Meadow for A Happening in Central Park (1967). Ramone worked on the live sound and soundtrack album of A Star is Born (1976). Over the years he has produced several tracks on Streisand albums, including Yentl, Till I Loved You, and The Essential Barbra Streisand.

[This interview originally appeared in All About Barbra magazine]

Matt Howe: Phil, for the Yentl soundtrack album, you produced the studio versions of “The Way He Makes Me Feel” and “No Matter What Happens.” Is it true you also created studio versions of “Papa Can You Hear Me” and “Piece of Sky”?

Phil Ramone: Yes, that’s true.

Howe: Why didn’t you release them? Was it because an LP could only hold 12 tracks or that the two studio versions you did include were the best out of the four?

Ramone: Yes, I think it’s more that and, to be honest about it, at the time Yentl was such a personal picture for her. The Bergmans and Michel Legrand wrote really amazing music. She had recorded the original tracks but there was a lot of noise on the tracks – camera people, creaking chairs and stuff. They went back and redid a lot of it in digital. So there was a lot of care that had to be done in making sure her phrasing … nothing got moved.

Howe: Are you talking about just the singing, or the dialogue soundtrack, too?

Ramone: It was 90% of it as far as I know. Once the picture had finally been put together and Columbia Records heard it, the perennial question of “where’s the single” [came up]. It’s not a record made with a rhythm section; it’s not a pop record in that sense. But you can ask any fan of Barbra’s and they’ll tell you note-for-note, lyric-for-lyric what goes on in that picture. You know, making a “pop record” for radio is very difficult because do you compromise? Do you not? Can you not just add stupid rhythm to something that’ll work?

You don’t. And so the phrasings and the readings of the so-called singles had a different meaning. Dave Grusin and I did those together.

Barbra’s wonderful about this kind of stuff. At first she wanted to reject [the singles] because they didn’t fit into the period of the picture. There are not too many percussion instruments running around [at the turn of the century]. How do you popularize it? How do you turn it around without cheapening or changing the intent of the picture? So that was part of the big challenge.

Mixing it for the movie is one set of circumstances. The other is making pop records. When you buy the album are [the fans] going to be upset? It’s a tough shoe to wear, because if you give them a record that goes to the top 10, let’s say, when you go buy the [album] it has nothing to do with what you did for the single version.

So there’s an interesting way in which we treated the music, and I think we succeeded.

Howe: I like the two pop singles. Of course, everyone’s always curious about what they don’t have …

Ramone: … the ones that didn’t make it.

Howe: Now we know they really exist.

Ramone: Yes, they do.

Howe: Have you recorded songs with Barbra that haven’t been released?

Ramone: Barbra’s a great collector, even on cassette, of everything she’s ever done. Her career is so vast that she’s recorded songs then withheld them because she didn’t like the way they came out. Sometimes I’ll see one in a compilation and I’ll say, “Oh, I remember doing that.”

Howe: Let’s talk about the first time you worked with Barbra. You engineered the sound for her in Central Park in 1967. In the introduction to the home video version of A Happening in Central Park, Barbra says that your cables got cut and you were worried that there wouldn’t be sound past the first ten rows. Was that the biggest challenge for that concert?

Ramone: Well, it was a challenge because we had to share the microphones between the record company’s truck and our independent truck. A spotlight was brought in, and when they lowered the back elevator off the truck that was carrying it, it cut right through the cables. You’ve never seen so many engineers with soldering guns … Not just the P.A. system was in jeopardy, but the recording system was jeopardized. About 5 o’clock that afternoon, the day of the concert, we finally got most of the cables back.

Howe: What else do you remember about the concert in Central Park?

Ramone: That’s a memorable show. It’s memorable for a lot of people. It was before the big Woodstock, massive audience concerts. Sound systems weren’t designed to do that. We added a whole, complete, additional system. Marty, Barbra’s manager, said to me, “You know I’m worried. Who knows how many people are going to show up? Can you make sure nobody yells, ‘We can’t hear you, Barbra’.” I said, “I promise you that won’t happen.”

They were concerned that there may be more than 10,000 or 15,000 people. I was experimenting with these “long throw” horns, which were humongous-looking, ugly horns on top of the scaffolding. But they were guaranteed to go at least 300-400 feet. And 300-400 feet is a lot. Of course, with the open air, and the sound bouncing off the buildings it added another couple of hundred feet. Little did any of us know that the sound of Barbra’s voice actually just lofted all the way up the park. People just kept walking closer and closer to the sound and romantically sitting near The Pond, which was quite a bit away from the stage. People were just enchanted. That was my first encounter with the city of New York and I didn’t get into trouble (laughs) “It’s too loud, it’s too loud.”

The guy’s truck that I was using, his Weimaraner, which is sort of a watch dog, got nervous. He bit a cop (laughs). There were so many sub-stories to that adventure. Crazy stuff. I’m not sure Barbra knows all the stories about trying to get [the sound] right. I mean, it absolutely poured rain that day. So we never had a sound check with her or her band. The orchestra said, “We can’t come out there with our violins and beautiful oboes. It’s too damp.” Around 5:30 or 6:00 they finally agreed. It had just started to dry up.

I remember the last shot, which is classic. The director had a long, long track for the camera to move slowly out away from Barbra as the last song played. It’s so funny because the people, they all sort of crowded towards Barbra. And the camera can’t make any move but back. I could hear [the director] saying, “I’m losing my shot! I’ve got nothing left.”

There are moments in those sessions – I’ve done about 3 or 4 of these monstrous gigs – and you just pray that nobody gets hurt, that the audience loves the show. Thank God, everybody was healthy, everybody was fine.

The album doesn’t really have all of what we did in the park. The recording of the Central Park concert was a nightmare because the label [Columbia] and her independent company (Ellbar) had me. The label produced what they did – they’re different sounding recordings.

I said to Barbra, now would be the time to do it, to revisit those specials, and A Star is Born, and really create a full Surround, digital kind of approach to them.

(Below: Phil Ramone, left, played a studio engineer opposite Gary Busey in “A Star is Born.”)

Howe: A Star is Born was the first Dolby picture?

Ramone: That’s correct. It’s the first Dolby picture. We started with First Artists. I got them interested and got Barbra to understand what we were trying to do – that it would cost around $5,000 per theater to refit the theater so it could play this movie, with a guarantee that if they didn’t like what they heard they could return the goods. It exploded for Dolby. It created a whole nest of wonderful things to happen to them. For us, it was some interesting stuff that had never been done – I set up a satellite between Todd-AO and the studios in Burbank and projected sounds back in forth, did all kinds of multitrack stuff that had never really been done before. I was brought in because the goal of that picture was to be all live – everything about it. There weren’t too many people encouraging that idea. [The studio] still made us prerecord the tracks for the movie in case Barbra wasn’t well or couldn’t sing; she could lip-synch – all those things that she never wanted to do.

So we were very fortunate. The band was live all the time. There’s nothing better than Barbra with a band, a small band. She was playing this up-and-coming star and so she’s supposed to be a kind of pop-rock artist. I’m sure you know the picture. [Kris Kristofferson plays] this irritable, wasted kind of performer. In the movie, of course, it’s his band that takes her on the road. So you have this mix of country and R&B players that create the soundtrack; then you add the lushness of the strings for the additional score and things like that.

[The sound on A Star is Born] was a work of art, and the work of a lot of people, great people. We did stuff that had never been done before, and against most motion picture rules – it cost more, something could go wrong; the risk that you don’t want to take a chance, like somebody doing their own stunts. (Laughs) Streisand did that.

[We created] the sound environment as you watch the concert in Arizona, with the helicopters flying over – you watch that scene and you know that you’re hearing something live. And the theater at the end of the picture. That’s all sung live, that lasted ten minutes. It’s as live as it can be – mistakes and all. On the record album, we only changed one thing, because she breaks down crying. Barbra felt that was just too far, just too much for the record. So we re-sang those lines where she chokes.

Those are elements in Barbra’s life that people don’t understand how good and amazing she is. No hi-fi magazine wrote anything at the time. That’s why I love to get calls [where people ask] “can you tell us what you did?” You don’t do anything around Barbra that doesn’t have recall-ability.

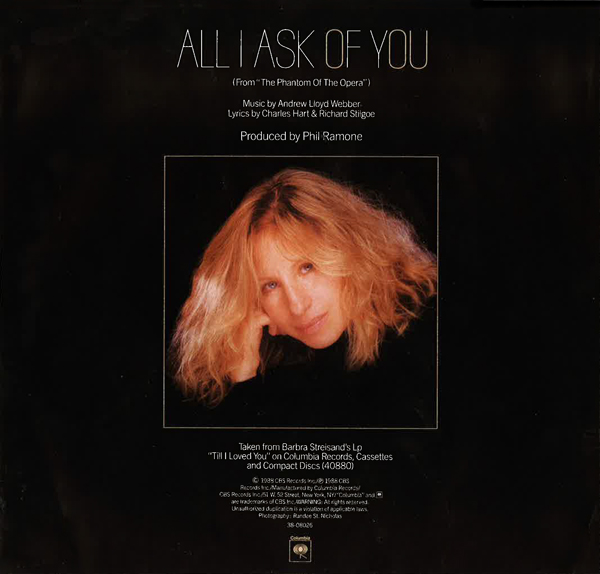

Howe: Can we talk about Till I Loved You? You worked on the duet with Don Johnson and also “All I Ask of You.” Rupert Holmes tried to record that song with Barbra earlier. They had a hard time getting the arrangement and lyrics just right. How did you take “All I Ask of You” from a duet in the show Phantom of the Opera to a solo version for Streisand and create such a great pop song?

Ramone: It’s an interesting concept – messing with Andrew Lloyd Webber stuff. It’s not easy. Barbra’s always approached music from both a lyrical point of view and a sensibility of, “why can’t I sing this? Why wouldn’t I sing this? Why wouldn’t I sing this to him?” You know, it’s established for too long that it’s a duet. You can take a song and re-voice it or change keys. But this song is written as a duet.

I don’t know, we just took a shot (laughs). We worked on it so it could be a meaningful song, as it is. Recently somebody called me who was interested in cutting another version of “All I Ask of You,” and asked, “Why did you do that, and how can you do that?” And I said, “Listen to it, and if it appeals to you, then go do it.” That kind of song could be over-the-top – it’s a dramatic song, plus the range of it is insane.

I’ve been very fortunate, any time I’m around Barbra. You get to do the most unique things that you don’t always do.

Howe: Did the lyricists, Charles Hart and Richard Stillgoe, work on Barbra’s version?

Ramone: Oh yeah, you always call [the lyricists]. It’s one of the classic things that Barbra’s capable of. She’s not afraid to make a change, make a lyrical point more poignant. Her friends, you know, are the Bergmans. Barbra’s the queen of listening and looking at lyrics. All of us who have been around great songs know what that means. The Bergmans, of course, have done quite a few with her.

I did “How Do You Keep the Music Playing” with Frank Sinatra [for his Duets II album]. I called the Bergmans and I said, “I’ve got a little bit of a problem, I’m creating a duet and I’m not sure how to get around one place [in the song].” They solved the problem. That’s the kind of thinking you want, where you can collaborate in the simplest form.

Howe: What’s it like actually recording with Barbra in the studio?

Ramone: I gauge every person and personality every day. I don’t formulize it. Because just when you think you have an answer – for example, it’s a bacon-and-egg sandwich and a glass of tea; that’s the routine, right? – you’re wrong, because it’ll change. And yet, we’re all creatures of habit. “Gee, I love when we took a break and that little restaurant made that salad for me. Can we have that?”

Barbra’s an incredibly hard worker. I remember, during Yentl, I would sometimes drive her home and she would say, “Ok, now we’ve got to get some rest because we have to be back at the mixing stage at 8:00.” So I’d get a call around 6:00 or 6:30 and she’d say “You know, that phrase…” And I’d say, “Barbra, have you slept?” (Laughs). She’d be on her treadmill talking to me on speaker phone. I would always expect her to call at any time. Sometimes [she doesn’t say] “How are you?” You miss all of those [niceties] because you want to get to the point.

I don’t like excuses and neither does she. We share a lot of the same qualities.

I had done Sinatra’s concerts and his Duets albums. Barbra was about to embark on her [1994] tour. And she had a Teleprompter built for the arenas. Poor Frank had just gotten murdered by the press – “Why does he need Teleprompters? He’s been singing these songs for 40 years, doesn’t he know the words?” And Barbra had the best answer. She said, “I’m very critical of my work, I don’t want to make a mistake.” End of subject. If Frank had every said that it would have been brilliant. He never did. He just took all the flack from the critics.

Howe: Phil, you’re quite involved with new technology.

Ramone: Barbra knows that I’m crazy about technology. It’s a way of life for me. When I was involved in doing [the Sinatra Duets album], Marty said to me, “Please don’t tell her you’re experimenting with this – doing your vocals from home.” (Laughs).

Howe: You’re speaking about ednet?

Ramone: It’s a way of life. Artists always say to me, “Boy, you should have heard me when I was warming up this morning. I wish you would have recorded me.” And I said, “Soon it’ll come! We’re working on it.”

Howe: Barbra has her own studio at home now.

Ramone: Of course. I mean, why not? When we finished A Star is Born, and she had the ranch, she moved the editing out there. And I moved out there. It was great! Why not work in your own home? I live on a farm. I have a big barn, and above it is the edit and video room … to work. And if I decide not to, it just stays closed. There’s so much work that comes up in the middle of the night and it’s hard to call a studio, book an engineer, get the receptionist ... It doesn’t have the instantaneous effect you need to go right to work. So, of course Barbra should have a studio at home – it’s better, far better.

She used to pull up in her small trailer, her dressing room truck that she owned. She didn’t need to sit in the lobby of every studio. You end up being a social person in a studio when you’re trying to sort out what’s wrong with the lyric. So she always had this little hideaway which parked right outside the studio where we were working. I thought that was clever.

Howe: Barbra’s duet with Sinatra was classic.

Ramone: For “I’ve Got a Crush on You” we were at Todd-AO. We did a whole new intro for her before Sinatra comes in. David Foster and I had fun with that, and a lot of laughs.

Howe: Did you help with the live version she did during her Timeless concerts?

Ramone: No. She was very complimentary at one of the concerts. She pointed at me. It was really nice because I was in the front row with her then new husband [James Brolin].

Howe: Do you have any future recording plans with Barbra?

Ramone: I’m waiting for the phone call. If they want something, I’m there.

Howe: What’s the next big thing in technology?

Ramone: The Surround thing is something I’ve been working on for a long time now. People won’t sit down in their living rooms and play records any more. But they will sit down and watch movies. I’m also working with a company to make a computer’s speakers small and efficient and great-sounding.

Howe: SACDs haven’t quite taken off, though.

Ramone: I’m looking for a better solution to make available to the artist and the public – Visuals when you want them … flip the DVD over and play only audio. I think people in cars want to hear them and watch them in the back seat. Not everything needs visual, but some of it could be artwork – things that belong to a record that used to be a habit when you bought an LP.

Howe: Someone showed me a DVD-Audio of Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours album that was so well-done. For the visuals, they used session sheets and photos of the band recording the album. You could click a button and isolate certain instruments. They also included some of the original demos. It was really amazing. Columbia should create something like that for Barbra’s albums.

Ramone: There ya go! Barbra should be the instigator of something like that.

Howe: As long as they have the original tapes, Columbia could go back and remix Barbra’s albums for 5.1 Surround Sound, right?

Ramone: Yeah. I’d do that for her in a second.

END.

Notes:

Dolby Laboratories developed a high-fidelity, stereo soundtrack for movies that applied noise reduction to decrease the hissing on the soundtrack, and also equalized the cinema’s sound speakers.

First Artists was a film production company established in 1969 by Sidney Poitier, Barbra Streisand, Steve McQueen and several other stars. Barbra produced Up the Sandbox, Star is Born, and The Main Event under the umbrella of First Artists.

Todd-AO is Hollywood’s big post-production sound facility.

ednet developed a system in which digital audio could be transmitted on a private network to remote locations via fiber optic cables. Ramone utilized this technology for Sinatra’s Duets album.

Super Audio CDs, created by Sony and Phillips, offer music at a higher resolution than regular CDs. Many SACDs are mixed for Surround Sound systems, but will still play on standard CD players. Columbia Records released Streisand’s The Movie Album in SACD format.

[ top of page ]