SHE DOESN'T WANT TO TALK,

SO SHE TELLS A STORY

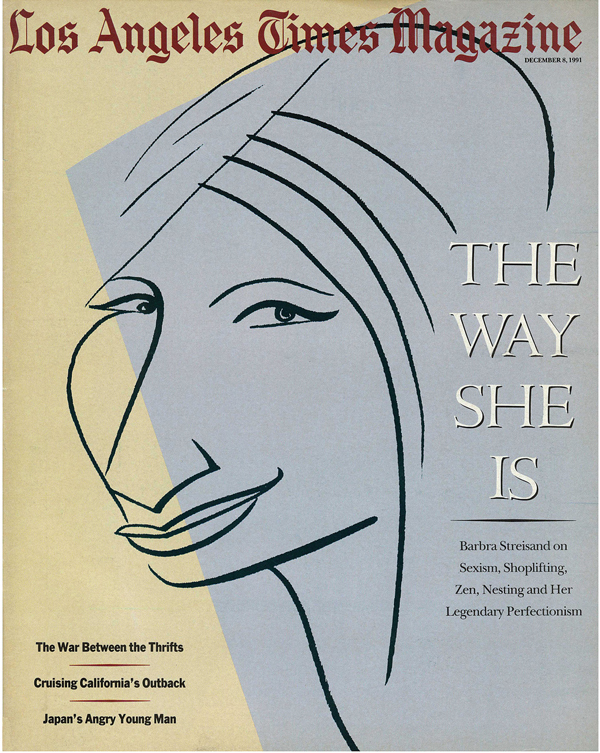

(Cover illustration: Timothy Carroll)

December 8, 1991

"The other day I went to the theater to see the trailer of my movie. And when I'm in New York, I, like, take a cab. I don't have a 24-hour-a-day limousine. I grew up in a poor family, and you don't think of hiring cars. But somebody from the theater must have called the paparazzi because the usher says, `There's three guys waiting for you in front.' And I'm in a sweat suit—schlocky—the way I'm dressed most of the time, to tell you the truth. Well, not schlocky, but. . . . So I started to run, and I could not get a cab. And it reminded me of when I first started on Broadway and the nights when I couldn't get a cab to my own show, and I would plead with people on Central Park West—tears running down my face-to take me to Broadway."

It's fairly vintage Barbra Streisand as these stories go: some pathos to patinate the glitz, a touch of self-deprecation partly recanted, more than a little theatricality and always, always, a reference to The Past. Not the "I Can Get It for You Wholesale" past that rocketed over Broadway nearly 30 years ago, piloted by the last real diva. No, it's that two-room walk-up, wait-till-I-get-to-Manhattan past-that Yiddisher Rosebud that Streisand keeps written on her psyche and woven into her speech. As she says, "If I'd had a normal childhood, I probably wouldn't be who I am today." She is telling this story at her New York home, the penthouse she's owned since her Miss Marmelstein days at the Shubert Theatre. She is supposed to be relaxing, antiquing and shopping prior to the Dec. 18 unveiling of her triple play as producer-director-star of "The Prince of Tides." But she breezes into her home office, her small, chiseled face set firm beneath her wispy hair, as if she's prepared for an exam: pencils, a pad of paper, a tape recorder clutched to her chest, suede pumps clicking on the hardwood floors. And then the phone rings. "That," she says without turning around, "should not be on," and a silence, swear to God, descends mid-ring. Streisand at 49 still wields impressive influence in an industry-any of the three she's mastered-not known to kowtow to women much, or at least not more than a few pictures', albums' or shows' worth. She is blessed with talent and wealth in a business that respects both. By merely saying yes, she made things happen-among them, 15 films, 48 albums, innumerable awards and a reputation, depending on the perspective, rivaling that of the vainglorious Ozymandias or George Bernard Shaw's St. Joan.

Today she hardly works anymore. An aloof, solitary figure, Streisand has withdrawn from the cultural mainstream, re-emerging infrequently to direct only those projects that strike a highly personal chord. Her dislike of singing in public has become all but an ironclad rule. Her attention to her homes, her antiques, her vegetable gardens, her stuff, is nearly as legendary as her talent.

"Garboesque," say those who've known her over the years, their voices scarcely above a whisper because many of her friends and enemies do not talk about her. From actor Elliott Gould, Streisand's former husband, to producer Jon Peters, her former companion, from "The Way We Were" director Sydney Pollack to her manager, Marty Erlichman, a collective chorus arises, usually sung by assistants: "I can't talk to you about her."

Of course, there is always the bland leading the bland. Music and movie mogul David Geffen: "Barbra is an artist, one of those rare people who can do anything she wants."

Mega-producer Ray Stark: "Barbra could do whatever she wants-and does. She could have been Joe Montana, H. Norman Schwarzkopf, Jonas Salk, Maggie Thatcher or Barbra Streisand. I think she made the right choice."

Even writer-director Frank Pierson, who had the courage or hubris, depending on your view, to tear into Streisand in a much publicized magazine article after directing her in "A Star Is Born" (1976), says today: "That's all in the past. `Yentl' was a spectacular directing debut, and you can quote me."

Go closer. Her longtime agent, Sue Mengers: "Her friends are very protective of her because she is hypersensitive to the press, and we respect her nervousness."

Closer. Cis Corman, her best friend: "It's fascinating to me that she is so put down by the media. People who know her love her."

Closest of all. "I never talk about myself except when I'm doing an interview," Streisand says, clicking on her recorder like she was cocking a gun. "I wish," she says, "we could talk about anything else except me."

(Photo by: Jurgen Vollmer)

SHE TELLS ANOTHER STORY. THIS ONE IS ABOUT HER CHILDHOOD in Brooklyn when she worked as a cashier at a Chinese restaurant after school and heard about the birds and the bees from the all-knowing proprietress. "When I come back to New York, I always think about Muriel Chow," Streisand says. "I've tried to find her a couple of times, but I never can."

Sitting here in Streisand's sun-dappled duplex high above Central Park West is a little like discovering that there actually is a Betty Crocker-but one who is more youthful, more attractive, more fun than her stern-faced persona-despite the presence of the tape recorder that Streisand maintains is for her own record keeping. She fairly jumps off the office couch to give an impromptu tour of her comfortable but not intimidating apartment, the first home she bought with her Broadway earnings after living in that "cold-water, $60-a-month railroad flat I had on 3rd Avenue."

She moves from room to room, opening doors, providing a running commentary on her French antiques, English antiques and now her latest passion, period American furniture. She had the museum-quality Gustav Stickley couch and chairs in her office re-upholstered in rose velvet to offset "the masculinity" of the wood. "My china is from 27 years ago, and look how it goes in this room now," she says, still clutching the tape recorder so that even this minor observation becomes the stuff of posterity. "Isn't this lovely?" she says, gesturing to her living room, as perfect as a stage set. "It's just like a little house."

There is nothing arbitrary about Streisand. Not in her homes (New York, Bel-Air and Malibu), not in her dress (on this afternoon, textural variations of black, ranging from her silky chenille sweater to her webbed fishnet stockings and suede pumps), not in her work, be it in the recording studio or on a movie set. Even her memories, several of which are recounted on this afternoon, seem re-upholstered. No madeleines are recollected without hunting down the damn recipe for updating in today's test kitchen.

It is what her colleagues refer to when they speak about Streisand's drive, her perfectionism, her watchmaker's attention to detail, whether it's turned on the elusive Mrs. Chow, the Stickley or her latest film or album. It is a trait that has contributed mightily to her reputation as a demanding—who would say difficult?—taskmistress.

"She asks `Why?' a lot," says Gary Smith, co-producer of Streisand's last live concert, her 1986 political benefit, "One Voice," held at her Malibu estate, as well as several of her early television specials. "Her instincts are great, but it can be frustrating to have to come up with answers every minute."

"She is demanding, no question about it," says songwriter Marilyn Bergman, who has known and worked with Streisand for nearly 25 years. "It can be annoying to those whose standards aren't as high."

Streisand prefers the term perfectionist. "I always had a very, very strong will," she says. "I just believed that people could do what they wanted.

"I used to have arguments when I was 5 or 6 with an atheist and a Catholic friend. I was the Jew. I believed in God very strongly, and I remember trying to prove to this atheist that there was a God. We were on her fire escape, and I said I am going to pray to God that that man on the curb steps into the gutter. We used to call it the gutter. And sure enough, the man walked across the street."

That belief in her own willpower has all but overtaken her voice as the engine of her career. It is as if her decades as a performer, beginning in 1960 as a post-Doris Day gamin—with Cleopatra makeup and a monkey fur coat—singing at Greenwich Village's Bon Soir club and culminating in an almost paralyzing fear of performing in public, have become something external to herself. "For me to sing my old songs would make me feel like I was not moving on," she says, "that I was living on my past glories."

(Above: Streisand with Nick Nolte in "The Prince of Tides": "I told her, `You're cutting the love scenes too early,' " he says.)

Her latest album, "Just for the Record . . . ," which debuted at No. 38 on the Billboard chart in September, is a four-CD retrospective spanning more than three decades and including 94 tracks, 67 of which were previously recorded but unreleased and only one newly recorded song. For the soundtrack album of "The Prince of Tides," Streisand sang a version of "For All We Know" but refused to include it in the film.

Opinions on Streisand's fealty toward her singing career differ. "Because it came easily and so early on," Bergman says, "Barbra tends to be almost offhand about her voice, to not take it as seriously as she might."

"She's like Brando about her voice," observes Pierson, "the world's greatest actor who has nothing but contempt for his skill."

Despite her having won the Best Actress Oscar for her first feature film, "Funny Girl," in 1969 (in a tie: Katharine Hepburn also won), Streisand has had difficulty shaking her reputation as a singer first and everything else-acting and directing-second. She has been criticized for her ardent-some have said arrogant-interest in wearing more than one hat.

"I don't get it," Streisand says with more irritation than bemusement, "(these criticisms) that I do more than one job."

Other criticisms—that she was egotistical, that she was controlling, that her career was being steered by Peters, a mere hairdresser, that she was, in the words of her agent, "a woman who did not kiss ass"—culminated with "Yentl," the film adaptation of Isaac Bashevis Singer's story, which Streisand labored for 15 years to bring to the screen as her directing debut. Streisand and "Yentl" received Golden Globes (best director and best musical or comedy picture of 1984) but barely a nod from the academy: Although "Yentl" was nominated in five categories, Streisand's acting and direction were ignored. The prevailing wisdom in Hollywood was that the film became a referendum on Streisand's personality.

"There's no doubt about it," according to one longtime industry observer, " `Yentl' would have been nominated for a Best Director (Academy Award) if it had been directed by a man."

Streisand's talent for running against convention-the industry's old-boy network-has resulted in her most oft-sung refrain: "These things would never be said of a man."

"Barbra thinks she has been held back by being a woman," says Geffen, who has known Streisand for several years. "But she has done everything she's wanted to do."

Yet Streisand is unusually quiet about voicing any criticism of the industry today, a time when the few female studio heads, such as Dawn Steele and Sherry Lansing, are no longer in place. "I think there is a really big problem, and a lot of it is women against other women," Streisand says, segueing into a discussion of the recent Senate hearings on Clarence Thomas' Supreme Court nomination. "It was like a witch hunt. But what I really resented were the other women who sounded like they were jealous of a woman (Anita Hill) who had great dignity. It makes me sick to see how women can be treated when they have more education and are smarter than other people-and that is no different in Hollywood or Washington."

Although Streisand is considered an old-fashioned political liberal, one who gives money to a variety of social causes through her Streisand Foundation (endowed largely from the $6.5-million proceeds and ancillary rights generated by her "One Voice" concert), the largest grants have not been made to Democratic or feminist causes but to the two chairs she endowed: the Streisand Chair in Cardiology at UCLA (in memory of her father, Emanuel) and the Streisand Chair on Intimacy and Sexuality at USC.

These days, Streisand seems less intent on presenting herself as a political or industry gadfly than as a director. Indeed, Streisand insists that beneath her balladeer's image, "I was always a director in a way. I remember being in Philadelphia with (pre-Broadway) `Wholesale,' and I had auditioned for the part in a chair, because I was nervous, and I thought it would be interesting staging, and it would be funny. But when I got the part, they proceeded to change the staging-until the night before we opened in Philadelphia, and they said, `Do it in your goddamn chair,' and it stopped the show. I remember being bawled out the next day, and I couldn't understand why they were so angry at me for being right."

She throws a lot of stories around-most of them from her childhood and early years in New York, many of them included in the liner notes of her retrospective album-to illustrate her points, to correct false impressions. Much of it seems designed to portray Streisand as the victim triumphant, one who creates art in the face of a deprived childhood, dictatorial directors and an anti-woman industry. The effect, however, is of someone anthologizing her life as she lives it, studying herself from a slight remove, with the lighting just so. "I'm just interested in the truth," she says blandly-swiftly, unsubtly setting the rules for this interview by flogging the other guy.

"That other article had so many things that were terribly incorrect," she says, referring to a piece in the September, 1991, issue of Vanity Fair. "The paragraph about my ambition (in the early days), that `I should have been arrested for indecent exposure,' that my ambition was bup, bup, bup," she says, launching into the little rap riff she employs when words can't keep pace with her thoughts. "I called up (the writer) and said, `Why did you write that?' "

Another article is mentioned, a Los Angeles Times review of her retrospective album that lamented that Streisand was "knowable then, much more so than the powerful and publicly polite but slightly removed figure we see and hear so infrequently today."

"I thought it was mean-spirited," she says. "I don't get why people are mean-spirited." And then pointedly, "What did you think of it?" Breezing by any demurrers, she invokes the hoariest of axioms. "I think the public has a right to know the truth. When I do an interview, you're going to see me for a couple of hours, and you can't possibly know me. There is so much more that I can express through my work. I always believe the work speaks for itself, and that's what will be remembered. So when somebody writes a statement like that about ambition-because I never went after anything-it's like trying to put me in a mold of `What Makes Sammy Run.' Like I'm an aggressive Jewish woman or something. That's not who I am. I'm a director, and that means I have a vision."

"NO, NO, NO. THE STORIES THAT YOU HEAR, YOU CANNOT USE them. You just never know a director until you work with them," Nick Nolte says as he reclines in a trailer in Pittsburgh, shooting another movie, finessing the overriding question about Streisand's ability as a director. Ever since the Oscar rumors began leaking out of the test screenings of "The Prince of Tides" last summer—good word of mouth that led to the film's repositioning as Columbia Pictures' Christmas entry in a very crowded field—Nolte has been besieged by a curious, even skeptical, press.

"Gossip you don't listen to," he rasps in his good-old-boy twang. "You look at their (the directors') work, and you call somebody you respect for their opinion. I called Karel Reisz and Sidney Lumet, and they encouraged me (to work with Streisand). And I decided this was absolutely the right piece for Barbra to direct."

He was not a shoo-in to play Tom Wingo, the repressed Southern football coach, the protagonist of Pat Conroy's best-selling novel. But then Streisand was not the first in line to direct the film adaptation, either.

Even before Conroy's epic family melodrama was published five years ago, "The Prince of Tides" was a movie project. Conroy has a reputation as a writer of Southern tales that translate well to the screen. "The Water Is Wide" (retitled "Conrack" for the film version), "The Great Santini" and "The Lords of Discipline" were all Conroy novels that have been made into films. When "The Prince of Tides" became available prior to publication in 1986, United Artists quickly acquired the rights, commissioning Conroy to write the screenplay.

In the ways of Hollywood, that draft turned into a revision, followed by rewrites accompanied by handoffs from one studio to another and from one star to another. At one point, Robert Redford was set to play Tom Wingo. "I thought it would be a good vehicle for us," says Streisand, who had starred with Redford in Sydney Pollack's "The Way We Were" in 1973.

Eventually, Redford dropped out, and Streisand, who had been interested in "Tides" since she heard about it in 1986 while filming "Nuts," signed on as producer, director and star of the psychological drama-cum-love story. She chose to play Susan Lowenstein, the New York psychiatrist who helps Wingo unravel his tortured past; she commissioned further script revisions and convinced studio heads that Nolte, fresh from his volatile performance in "Q & A," was right for the role ("I said, `Have some faith in me as a director' "), hired her son, actor Jason Gould, 24, to play her character's son ("I thought everyone would take swipes at me and my son, but he was just the best one") and moved the film to Columbia, then under the wing of her former companion and producer, Jon Peters.

If her triple credits on the film raised some suspicions within the industry about her-indeed anyone's-ability to fulfill the demands of three jobs, Columbia never blinked. Even after Peters' abrupt and unexpected departure from the studio last spring, Columbia's Frank Price (who himself left the studio this fall) supported Streisand through 10 days of cost and time overruns.

Directing only her second film in nearly a decade, Streisand was as passionate about "The Prince of Tides" as she had been about "Yentl," bringing much of her own life, and more than a few of her newly adopted New Age theories-including the beliefs of therapy guru John Bradshaw-to bear on her film.

"I think she read `Prince of Tides' seven times," says friend Cis Corman, president of Barwood Films, Streisand's production company. "She knew the book so well she would tell Pat what he had written on Page 376. I mean, after `Yentl,' she could have become a rabbi. Look, it's a painful process for her but with moments of joy."

"Every film she directs involves a working out of a part of her own life," Bergman adds. " `Prince of Tides' is about family and forgiveness, about Barbra forgiving her father and her mother."

"A lot of this movie is very meaningful to me because it's about not blaming your parents," Streisand says. "We've all come from some type of painful childhood. But if you blame your parents, it keeps you the victim," she says, adding that "the mother in me makes me possibly a better director. Women can bring a certain kind of nurturing quality to a film."

Nurturing is not the word that is most often heard in conjunction with Streisand's directorial manner. "Unbelievably prepared" is how actress Kate Nelligan, who plays Lila, Tom Wingo's mother, describes Streisand's exhaustive-and exhausting-attention to detail. During the film's three-month shoot in New York and South Carolina last year, Streisand insisted on take after take-frequently shooting two versions of a scene to increase her options in the editing room. She was concerned with every aspect of the production, from Nolte's weight (she asked him to drop 30 pounds) to the exact shade of yellow in the silk blouse she wore in some of her own scenes and the nuances of the Southern accent used by Nelligan. "You think you know people who work hard-then you see Barbra," Nelligan says.

As for Streisand's ability to juggle directing with acting, she says simply, "I don't think about acting much. It is easier if the part is very much you. And this character I understood very well."

Nolte, however, suggests that Streisand initially found the dual tasks a challenge, "particularly in the love scenes, where she would cut too early," the actor says, launching into an affectionate mimicry of Streisand in mid-rant. "I told her, `You're cutting too early,' that it (the scene) would start to feel too good, and she would cut. Then Barbra looked at dailies and said, `You're right; I don't know what nut is cutting too early.' "

"I don't find it that easy to bare my soul, to do intimate things in front of a camera," Streisand admits. "I'd rather do it in private . . . which is why I probably am not as good as I could be in terms of being an actress."

Nolte is one of the few willing to suggest that it is Streisand's talent for performing that works against her abilities as an actress. "It's really a lonely job to be a singer, a totally different mentality," Nolte says. "As an entertainer, it's all about me. The lights have to be right for me. (Entertainers) come on the set, and they don't know how to share. They don't want to stick around for off-camera work. They have not grown up with a sense of teamsmanship. It makes it very hard for them to be taken seriously in the acting community. Barbra's much more tolerant as a director. You really don't have time to focus on yourself, and in that position she works real fine."

Streisand acknowledges the change in herself behind the camera. "When I direct, I become very patient, very compromising, for a perfectionist. There is a certain kind of acceptance of things you cannot change that would be very helpful in life. I live my life when I'm directing the way I would like to live my life when I'm not directing."

"OF COURSE I NEEDED THE MONEY,"Streisand says, goosing her story-this one about her shoplifting adventures for pin money in Brooklyn-with that trill-like laugh evocative of the giddy charm she displayed clomping around the Winter Garden Theatre 27 years ago belting out "I'm the Greatest Star" in "Funny Girl."

"I wouldn't just take stuff," Streisand says. "I would walk around the store until I found a receipt on the floor and then go get that item-a compact, a lipstick, whatever-and return it for the money."

She acquired her survivor instincts shortly after her birth on April 24, 1942, in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn. When she was 15 months old, her father, Emanuel, a teacher, died of a cerebral hemorrhage. She has one older brother, Sheldon; her mother, Diana, worked as a secretary in the New York public school system.

"I slept in my mother's bed, my brother slept on a cot. We never had a living room, never had a couch," Streisand says. "Maybe that's why I love couches so much. My mother had plastic slipcovers on everything, newspapers on the floor. Where did I get my sense of aesthetics?"

She tells these tales of her childhood-her mother's remarriage to Lou Kind, a used-car salesman, the birth of her half-sister, Roslyn, her refusal to eat, her groveling for affection-as if she were still panning for clues about her own evolution to superstar from the daughter she says her mother described as "too skinny, different, not pretty enough, too intense."

"I wanted to be an actress, but my mother did everything to discourage me. She wanted to be an actress or a singer but never had the courage. She tried to get me work in the school system as a typist," says Streisand, who made her first recording at age 13 with her mother (who recorded two operettas at the same session) at a studio in New York City. "My mother was very shy. I'm very shy, but I just knew I couldn't live the life I was living."

She terminated that life in Brooklyn quickly, graduated from high school at 15 and moved to Manhattan, where she camped out in friends' living rooms and sought work as an actress. "I made the rounds for two days in New York," she says. "I went up for the part of a beatnik, and I looked like a beatnik. You didn't have to act to get the part, it was a walk-on. But they said, `We have to see your work.' And I said, `How can I get any work if you have to see me work? I can never get a job this way.' And I was feeling this strange power struggle. I felt that it was a very undignified position to ask anyone for a job. I decided I would design hats before I begged anyone for a job. That's when I started to sing."

Cut to Fishkill, N.Y., the early '60s: a summer-stock production of "The Boy Friend," in which Streisand has landed the tiny part of the French maid, singing one short song. "She was extraordinary," recalls actor Ron Rifkin, who also was performing at the theater that summer. "She made up this crazy accent-French from the moon-and during the rehearsal lunch breaks, she wouldn't eat but would stay in the empty theater practicing `A Sleepin' Bee.' She had a single-mindedness about her, a drive that I had never seen before."

Her resume begins informally as a singer in New York's gay bars and officially at the Bon Soir club, where she met her soon-to-be manager, Marty Erlichman, in 1961. One year later, she was on Broadway. Streisand won a best-supporting-actress award from the New York Drama Critics. Her debut album and her portrayal of singer-comedienne Fanny Brice in "Funny Girl" made her famous by age 22. She would go on to become the only artist ever to be honored with Academy, Tony, Emmy, Grammy and Golden Globe awards.

She was a one-woman phenomenon, one that marked the nation's cultural landscape as well as its notions of feminine beauty. As critic Pauline Kael put it in a review, "Streisand was proof that talent was . . . beauty."

"Barbra was unique," recalls Ray Stark, who produced the Broadway and film versions of "Funny Girl" and signed Streisand to a four-picture contract. "She had the aura and charisma of Fanny Brice on stage, as well as that incomparable voice."

Streisand seems ambivalent about this part of her past. "I'm fascinated by the moments we remember," she says. "I don't remember being on the Johnny Carson show seven times. I remember the first time I walked out of the subway from Brooklyn at 50th and 7th Avenue." She doesn't remember the opening of "Funny Girl," only writer-director Arthur Laurents' lecture on her performance as Miss Marmelstein—"on why I would never make it because I was undisciplined." She does not, as she says, "remember the good things."

Her voice, for instance. It is, Streisand suggests, a physical attribute. "When I sing, the emotional connection is made involuntarily," she says, gesturing to her throat and her heart. "When I sing, something happens, and I can't even tell you what is in that process, a certain musicality to the voice that is not even verbal. Speaking is sometimes harder to connect the heart and the throat."

And for good measure: "I don't know how to sing on the beat, and I think you have to sing on the beat in pop music. I don't feel at home in that music. I'm more suited to ballads, show tunes, emotional songs.

"You know what I never like in interviews?" Streisand asks, interrupting herself. "It's that I talk a lot about the same issues. With Mike Wallace (on "60 Minutes"), I actually started to cry when talking about my stepfather. I have certain unresolved issues, and the truth is I never really grieved over them," she says.

Talk to Streisand long enough, and her conversation veers toward an almost solipsistic review of her childhood and particularly of the father she never knew. "Because I didn't have a father," she says, "I led a very undisciplined life. We never ate as a family. I didn't have any boundaries.

"Even though I never knew him, I am very much like my father," she says, ticking off the similarities. "He was on the debating team, interested in French dramatics. He was very good at math. I was very good at math. At 16, he wrote a paper about all the things he loved at 16, and I read it, and it was all the things I loved at 16. I read Tolstoy for the first time, (heard) classical music for the first time. I went to the 42nd Street Library and read (Victorien) Sardou, Alexandre Dumas. That was the most exciting time of my life, I think."

Streisand has spent many years speaking about her father and her childhood in a variety of therapeutic formats, New Age and otherwise.

"I don't believe in psychoanalysis per se. . . . But that's what makes up our personality. Only when you get older can you look at things with some distance, and, if you have the courage, you can feel the pain," she says. "Even though you complain about your parents, you find you like them in many ways. . . .

"When I was 13 years old, a group of us auditioned for a radio show as actresses. I did a speech from `Saint Joan'-`He who tells the truth shall surely be caught.' I always felt that about myself. Years ago, when I talked about my fears and my anxieties, no one had any interest. And once you get rich and famous, you're not allowed to have those feelings."

She portrays herself as a truthteller, but she remains ultimately a storyteller, fascinated with tales of herself and her past. Like many artists, she transforms parts of her own life into her work. "When something is really good, it comes from the kishkes, the gut, the subconscious," she says. But when her stories are not heard, embraced or believed, she portrays herself as a victim-of an unhappy childhood, an uncharitable industry, a sexist world.

"When women get hurt, whether from sexual harassment or by being ridiculed for being all they can be-which is why I made `Yentl,' a story of a woman being all she can be-we get put down for that. . . . I kept thinking about Freud during the (Clarence Thomas) hearings, and it reminded me that women are not believed."

Perhaps hers is a practiced response, a constant reopening of old wounds, a re-examining of slights, a way to keep herself at odds with the rest of us, a way to keep herself singular. Streisand sighs and fiddles with her tape recorder. "I have mixed feelings about that. One part of me says you don't tamper with something that is a God-given gift. I don't know why I have a certain talent. Not really. We can conjecture. My voice came from my mother. It's in the physiology of my being. I do have something to offer. It's why I am here. But I guess I don't like to think about it too much."

Friends say Streisand is happier now than she has ever been. Or rather, "she is capable of being happier than she has ever been in her life," Bergman says.

"She doesn't work a lot," Mengers explains, "because she doesn't like herself during that period, it frightens her a little, and she has reached a point in her life where she is more accessible, more open to meeting people now than she was 10 years ago."

While Streisand remains close to her mother and her half-sister, Roslyn, who live near her in a condominium that she purchased for them in Los Angeles (she is less close to her brother, Sheldon, who lives on Long Island), and has become "good friends" with her son, Jason, as one friend puts it, others suggest that what Streisand most desires these days "is a satisfying relationship. She has realized that her career is not her life," confides one friend.

Streisand has been publicly linked with a number of famous men over the years, including Jon Peters, Richard Baskin, a composer and heir to the Baskin-Robbins fortune, actor Don Johnson and, more recently, James Newton Howard, who composed the music for "The Prince of Tides." "Barbara has few relationships; they are quiet, and they don't last too long," one friend says.

Streisand confesses that she is "thinking about how I want to spend the rest of my life." Options include "maybe just acting or maybe just directing. I want to travel, I want to work with children. I feel a lack of children in my life. My son is very grown-up. I was thinking of adopting a child, but I'm not too sure I want to do that as a single parent. It wasn't too hot for me, and I don't particularly want to do that to another child.

"You know, I read something, a book called `Chop Wood, Carry Water,' " Streisand says. "It's kind of a Zen book. I think I would be much happier if I would chop wood and carry water instead of making movies and being attacked. I would like that. I like it when I'm not in the limelight for three years. People say I don't work much, but I get very happy in those years. Well, not very happy, but happier. I have no need to sing, act, direct. I like to nest, design houses, things not for public consumption. The work takes things away from me, it isolates me," she says, pausing. "On the other hand, I'm very grateful for my work. At the sad times, I can always say, `I have my work to fall back on, that it has been a great friend.' "

Streisand's tape recorder suddenly runs out of tape, snapping off, swear to God, at the end of that sentence. "That's a good line to end on," she says, smiling at the timing. "The work is a really great companion."

BUT THE AFTERNOON DOES not end there. Streisand wants to show off her latest purchases. She heads into her front hall, opens the closet and begins pulling out dresses, coats, hats, new and old, that she recently bought.

"I went to this antiques show last night, and I didn't buy one stick of furniture except a Shaker pincushion. I bought antique clothes. Isn't that incredible?" she asks, emerging, her arm extended with a black-velvet evening coat. "All that gorgeous velvet and the sequins on the pockets. It fits me to a T, and only $350," she says, twirling the coat in the hallway. "I would rather give my money to charity than spend it on very expensive clothes that I would wear only once. I wear my clothes over and over again."

She reaches up into the closet for a new hat, moves to the front of the hall mirror and jams the cloche tight on her head, studying the effect with slight turns of her head. "I like hats," she says, "because I don't have to worry about my hair."

The discussion turns briefly to the two antique gold rings-one Egyptian, one Greek-she wears. "Twenty-two karat," she says, turning her hands in the light. "Isn't that gorgeous? I love this color gold. Don't you think it's extraordinary that these have lasted for thousands of years? This one is 5,000 years old, and that one is 3,000 years."

Why this passion for antiquities? "Because I love ancient myths," she says, speaking almost as much for her own life as for the rings on her fingers. "I love things that have survived."

END.

[ top of page ]