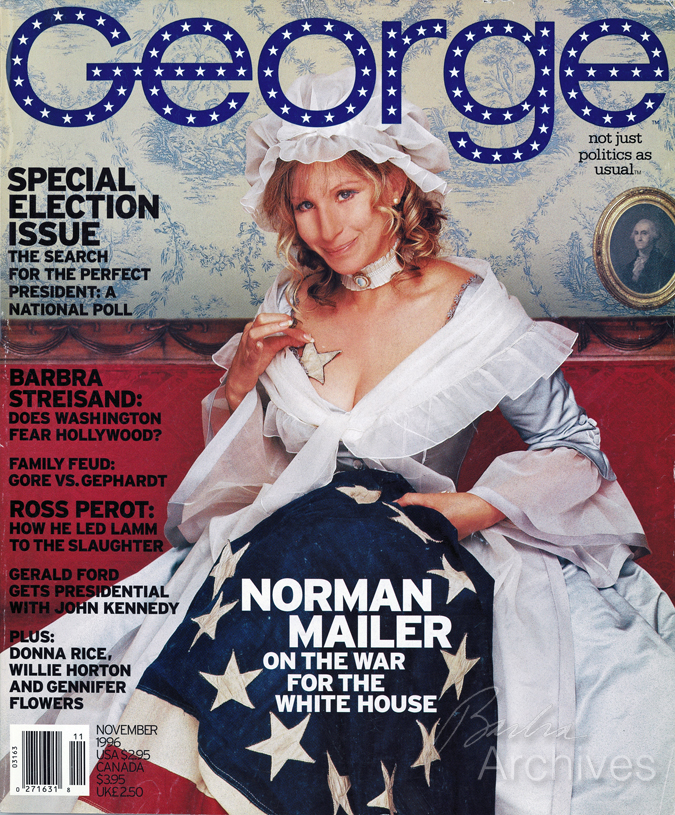

George Magazine

November 1996

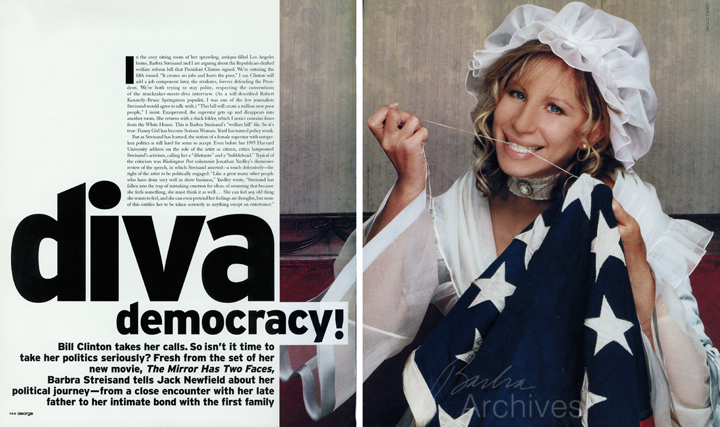

Diva Democracy

by Jack Newfield

Barbra Streisand photographed by Firooz Zahedi

Hair by Susan Germanie for Hollywood Backstage

Children's Pastime wallpaper by Schumacher

Styling by Rick Floyd/SmashBox

Bill Clinton takes her calls. So isn't it time to take her politics seriously? Fresh from the set of her new movie, The Mirror Has Two Faces, Barbra Streisand tells Jack Newfield about her political journey — from a close encounter with her late father to her intimate bond with the first family.

In the cozy sitting room of her sprawling, antique-filled Los Angeles home, Barbra Streisand and I are arguing about the Republican-drafted welfare reform bill that President Clinton signed. We're entering the fifth round. "It creates no jobs and hurts the poor," I say. Clinton will add a job component later, she retaliates, forever defending the President. We're both trying to stay polite, respecting the conventions of the muckraker-meets-diva interview. (As a self-described Robert Kennedy-Bruce Springsteen populist, I was one of the few journalists Streisand would agree to talk with.) "This bill will create a million new poor people," I insist. Exasperated, the superstar gets up and disappears into another room. She returns with a thick folder, which I notice contains faxes from the White House. This is Barbra Streisand's "welfare bill" file. So it's true: Funny Girl has become Serious Woman. Yentl has turned policy wonk.

But as Streisand has learned, the notion of a female superstar with outspoken polices is still hard for some to accept. Even before her 1995 Harvard University address on the role of the artist as citizen, critics lampooned Streisand's activism, calling her a "dilettante" and a "bubblehead." Typical of the criticism was Washington Post columnist Jonathan Yardley's dismissive review of the speech, in which Streisand asserted — a touch defensively — the right of the artist to be politically engaged: "Like a great many other people who have done very well in show business," Yardley wrote, "Streisand has fallen into the trap of mistaking emotion for ideas, of assuming that because she feels something, she must think it as well.... She can feel any old thing she wants to feel, and she can even pretend her feelings are thoughts, but none of this entitles her to be taken seriously as anything except an entertainer."

But if emotions don't earn her legitimacy as a political force, Streisand's record should. Critics tend to forget that the star's political activism predates by more than 25 years her current, high-profile identification as a Friend of Bill, which became official when she sang at his inaugural gala in January 1993. Streisand, now 54, has used her stardom to support liberal causes ever since she sang for another Democratic president, John F. Kennedy, in 1963. She's sung at benefits for the American Civil Liberties Union and Martin Luther King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference; spoken out for gay rights; and raised funds for liberal candidates. Unlike most stars, who aren't willing to do more than lend their names to a safe issue or make appearances at star-studded benefits, Streisand will jump into the arena, get her fingernails dirty, research a politician's career and harness monumental fundraising abilities to get him or her elected. Since the 1980s, she's helped elect dozens of Democrats to the House and the Senate, not to mention Bill Clinton for whom she raised $1.5 million at a 1992 concert and about $4 million at another benefit this past September.

"Streisand is one of the very few superstars who are proactive in their politics," says Danny Goldberg, the president of Mercury Records. "She is willing to take risks, to be the first person to do something. Bette Midler and Neil Young are great, but they don't get out there and try to elect individuals they believe in. [Barbra] is unique. She has filled the vacuum of leadership that was created when Warren Beatty got disillusioned and withdrew a little bit."

Today Streisand is Hollywood's largest single celebrity donor to political campaigns. Between January 1991 and July 1996, she donated $142,825 other own money to carefully selected liberal candidates. The runner-up is Don Henley of the Eagles, who has contributed $107,685, followed by Dustin Hoftman with $96,500. This election cycle, Streisand has contributed the legal maximum to senators John Kerry, Carl Levin, Tom Harldn and Paul Wellstone and to Jesse Helms's adversary, Harvey Gantt. But, she says with pointed passion, "I will not give one dollar to the Democratic Senate Campaign Committee, because they distribute the money to anti-choice Democrats in the South."

It may be that almost anyone born in Brooklyn to working-class Jewish parents during FDR's final years is destined to be a Democrat. "We were really poor," recalls Streisand, who grew up just three blocks from me on Pulaski Street in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn. "I didn't have any toys or dolls. I remember once making a doll out of a hot-water bottle."

She credits not only economic deprivation but also extreme family dysfunction for making her empathize with society's outsiders and casualties, a sentiment that has shaped her political beliefs. She detested her verbally abusive, often absent, philandering stepfather, Louis Kind, and was angry at her mother for not standing up to him. On August 4, 1943, when Streisand was 15 months old, her father, Emanuel, who taught high school, died unexpectedly — an event that created a lifelong sense of loss and abandonment. "As a child, I felt like an outsider and an underdog in my own house," Streisand says. "I remember usually eating standing up over the pot on the stove. Even on the Sabbath there weren't any sit-down meals where the whole family ate together." Yet Streisand wasn't a shy and retiring outcast: "I was definitely a rebel," she remembers. "In yeshiva school they told us to never say the word Christmas. But I couldn't buy into that concept. I would say it anyway."

Streisand's liberal politics were also grounded in her Judaism. "[In yeshiva] I was taught about the concept of tikkun olam — the responsibility for repairing the world," she says. "I was taught about charity, about putting money in a pushke for the needy. I was taught to invite a stranger to share your Sabbath dinner."

The greatest moral compass in her political life, however, remains her late father, a humanitarian who once wrote a thesis on how to teach literature to prison inmates. "I didn't get to know him," she says, "but he had a great, great influence on me. I feel like I am my father's daughter today. I am an extension of him." Streisand goes on to describe a mystical experience in which she communicated with the spirit other deceased father in 1979. At the time, she was agonizing over whether to direct Yentl, a feminist movie about a female rabbinical student who was forced to disguise herself as her dead brother, Anshel, in order to continue her studies. As Streisand relayed the strange anecdote, I interrupted her with a warning that her critics might use it to make fun other. (She had confided this intimate memory to one other writer, novelist Chaim Potok, in an interview more than ten years ago.) But Streisand was determined to relate the episode that was obviously crucial to her odyssey of self-discovery.

"This story starts with my brother Sheldon," she said, "who is very pragmatic, a sensible man and a real-estate executive. In the fall of 1979, while I was trying to get the courage to direct Yentl, Sheldon and I visited my father's grave in Mount Hebron Cemetery in Queens. I had never visited it before. My mother never talked about my father. I never had a picture of myself with my father. I thought I was born of an immaculate conception since I never knew him. I asked my brother to take a picture of me standing next to my father's headstone to show that he existed."

She stops, leaves the room and brings back a black-and-white photo of a very sad Streisand standing next to her father's grave. "See that name," she says with quiet emotion, pointing to the adjacent headstone in the corner of the frame. "The man buried next to my father is named Anchel. To me, this was a sign that I should make this movie."

A few days later, Streisand and her "sensible suburban brother" attended a seance with a psychic. Streisand received two messages from "Daddy": "The first one was 'sorry,' which was astounding because I was angry at him for leaving me. The second message was 'sing proud.' I know it sounds crazy, but it was my father telling me to have the courage of my convictions. I made Yentl. And I did sing proud."

Another, almost religious, formative political experience for Streisand was going to see The Diary of Anne Frank, in April 1956, for her fourteenth birthday. The play, starring Susan Strasberg (daughter of acting teacher Lee Strasberg) as the doomed victim of the Holocaust, was her first experience of Broadway theater. "I identified tremendously with Anne," Streisand recalls. "We were both Jewish, and we were both 14." Today, Streisand views her political role as defending the Anne Franks of the world, the victims of discrimination and persecution.

In the summer of 1970, I happened to be present for Streisand's first plunge into street-level partisan politics. The Oscar winner stood with a microphone on a flatbed and campaigned for Bella Abzug — the feminist, anti-Vietnam War candidate for a Manhattan congressional seat. The colorful motorcade and attendant publicity helped give Abzug the momentum to pull off an upset triumph in a closely fought Democratic primary. Streisand remembers feeling "an instinctive attraction to Bella. She was so smart, so eloquent, so opinionated.... I didn't really enjoy campaigning or singing on the truck. I have always had this stage phobia. But I did it for Bella." For her part, Abzug calls Streisand "one of the most unique people of our time," who is "not afraid to express herself."

Streisand cites two other women as inspirations for her political activism. One is Oscar-winning songwriter Marilyn Bergman, who co-wrote her hit song "The Way We Were" and is considered by many to be the most influential thinker in the Hollywood Women's Political Committee (HWPC), a liberal fundraising and lobbying group. The other person is Shirley MacLaine, whose political engagement Streisand cites as a model for her own journey. Possibly the only female superstar to have matched Streisand's high political profile, MacLaine was a California delegate for Robert Kennedy in 1968 and a tireless campaigner for George McGovern in 1972. Streisand also names as part other circle of advisers Senator Chris Dodd of Connecticut; Jesse Jackson's strategist Robert Borosage; and Ken Sunshine, a former aide to Bella Abzug who is now Streisand's public relations consultant. In the midst of discussing her political mentors, Streisand leads me into her study and shows me a black binder. "The Nation magazine," she informs me. "I love it. I keep every copy. I've never thrown one out. I keep them bound."

Streisand was politically dormant during the late '70s and early '80s — the years of her volcanic love affair with hairdresser and future producer Jon Peters. But in 1986 she began to plan the seminal event that would make her a singular force in politics. Streisand was spurred to action by the explosion at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in the Soviet Union. "I was very upset," she recalls, "so I called Marilyn Bergman and we started talking about the world and nuclear disarmament." As a result of these conversations, Streisand joined the HWPC and, in her perpetual student style, began to meet with academic experts on nuclear issues, advancing her education with suggested readings, including Robert Scheer's book on the Reagan administration's nuclear policies. It was Bergman, though, who focused Streisand's desire to affect change on the concrete idea that she could help elect specific liberal Democrats to the Senate in 1986.

The idea quickly became fact. Streisand would give a concert to be broadcast by HBO at her secluded Malibu estate and sell tickets for $5,000 per couple. The proceeds would be distributed by the HWPC to six pro-choice, anti-nuclear Senate candidates: Alan Cranston, Patrick Leahy, Tom Daschle, Barbara Mikulski, Timothy Wirth and Bob Edgar.

The fundraising concert was a stunning success. The HBO show got rave reviews, and the HWPC took in $1.5 million. Of the six candidates, five were elected, putting HWPC on the map as a major power to be reckoned with — and sucked up to. In 1986, the Democrats regained a Senate majority and, a year later, blocked the nomination of Robert Bork to the Supreme Court, averting an attack on legal abortion.

Today, Streisand is still miffed at Tom Daschle, now the minority leader of the Senate. "One of his aides was quoted in the Washington Post putting down the HWPC a couple years after the event," Streisand says. "I don't think politicians should take our money and then try to disassociate themselves from us afterward."

Still, it may be impossible for any star of Streisand's wattage not to be perceived by some factions as a glitzy dabbler sashaying into the political arena. Despite her efforts to research issues, she is not a policy expert and has no desire to run for public office, saying, "I don't want to go around shaking hands and having babies pee on me." Nonetheless, she accuses her critics of having a sexist double standard that allows male actors like Charlton Heston, Warren Beatty and Paul Newman to be politically engaged without generating controversy. In fact, they are often commended for their good citizenship. People are threatened by a sexual woman such as herself, Streisand says. "I'm a feminist, Jewish, opinionated, liberal woman. I push a lot of buttons." Indeed, in this era of cautious, apolitical superstars such as Tom Cruise, Steven Seagal, and Michael Jackson, Streisand has stood firm for the often unfashionable notion of the politically engaged star. "Most Hollywood liberals feel politics is impure," Streisand says. "They only want to help on a particular issue. But I wanted to actually elect the right people. That's the only way to change things."

Because of her willingness to dive into the muck of electoral politics, to educate herself on the issues and to use her star power to raise big bucks, she will succeed. Her political organization, the Streisand Foundation, which is administered by the savvy organizer Margery Tabankin, has doled out $10.2 million over the last ten years, mostly to national and grassroots liberal groups. Friends say that Streisand occasionally speaks directly to the President about policy and legislation, a fact that Clinton adviser George Stephanopoulos confirms. "I don't want to give the impression that she's on the White House staff," he says. "But when the President speaks to her, he values what she has to say."

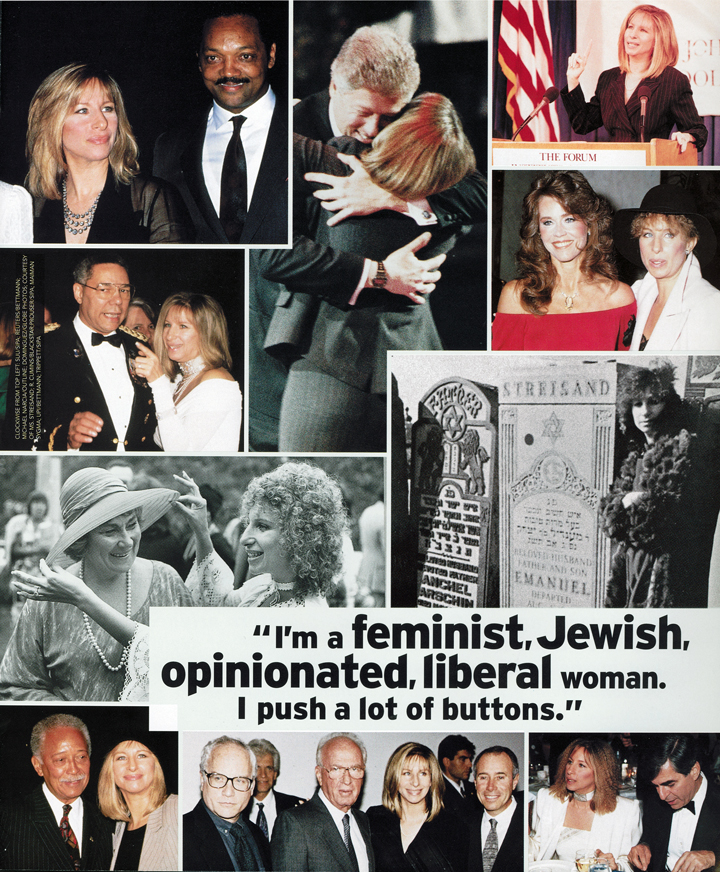

Clockwise from upper left: Streisand with then presidential candidate Jesse Jackson; in a Clinton clutch at his inaugural gala; behind the podium at Harvard; with Jane Fonda at an HWPC event; visiting her father's grave in 1979; supporting Michael Dukakis in '88; with actor Richard Dreyfuss, late Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin and mogul David Geffen; with former New York mayor David Dinkins; at her '76 benefit for Congresswoman Bella Abzug; with General Colin Powell at a '93 White House dinner.

Streisand first met Clinton in the spring of 1992 at the home of Interscope Records owner Ted Field, during a small meet-the-candidate gathering for activists in the entertainment industry. After her first choice, the populist Tom Harkin, dropped out of the Democratic primaries, she considered Clinton to be "the only viable candidate." Streisand was sufficiently impressed by their conversation that evening to agree to headline at a pre-election benefit for him and to perform at his inaugural bash. It was at the inaugural, however, that she met the person who would cement her commitment to Clinton: Virginia Kelly, the President's late mother. "When they met, there was this profound magnetic connection between them," says Tabankin. "They became very close." Until Kelly's death in January 1994, the two spoke by phone several times a week. "I think Virginia brought very motherlike qualities to Barbra's life," Tabankin says, "and Barbra became the young woman that Virginia never got to raise." Streisand was one of the last people to speak with Kelly the night before she succumbed to breast cancer. The star, who flew to Arkansas for the funeral, endowed a breast-cancer research program in Kelly's name at the University of Arkansas's Medical School with a gift of $250,000. "So her relationship with the Clinton family goes much deeper than simply agreeing with the policies of the President," says Tabankin.

Or disagreeing. Streisand's deep loyalty to the President became apparent as we argued over the welfare bill, which was the only time during our interview when Streisand did not seem in command.

"It hurts the poor," I assert again from across the couch. (Although Streisand and I will both vote for Clinton, we come from slightly different liberal traditions. I think economic justice is the most important issue; Streisand places higher emphasis on feminism, civil liberties and the environment.) Streisand freezes, panicking for an instant. She doesn't want to be quoted attacking Clinton in an article scheduled to appear during the last weeks of the presidential campaign. On the other hand, 21 senators that Streisand supported had voted against the bill, and the star's most intimate advisers, such as Bergman and Tabankin, were critical of Clinton for signing it.

She begins by saying, "I think Clinton is a great president." When pressed on the objectionable provisions of the bill, she allows, "I wish he had not signed it in its present form, but I also have faith that he will change it. He's still a great president." Then, she adds, in a demonstration of her authentic insiderdom, "Did you know that Hillary urged him to sign it?"

"Well, did you know that Senator Wellstone voted against the welfare bill?" I respond. "And he's up for re-election this year, but he has the courage of his convictions."

"Well, I gave Wellstone $2,000 this year," she says. "I think he's fantastic."

She looks through her file on the welfare bill and tries to regurgitate the party line but quickly gives up. "Look," she says, "I've been involved in postproduction on my film The Mirror Has Two Faces the last couple months. I haven't kept up. I don't know everything about this bill. I don't like it on the surface, but I don't know enough about it." Finally, she blurts out her deepest hope: "I believe the President will improve the bill in the next session of Congress by creating jobs."

As Streisand declared in her Harvard speech, "I have opinions. No one has to agree." Nonetheless, her political judgments have stood the test of time remarkably well. When all the wise men from Harvard assured the nation that the Vietnam War was winnable, Streisand, who never went to college, knew better. When Richard Nixon and Pat Buchanan were trashing Martin Luther King, Jr., she was singing for him at a benefit. When legal abortion was hanging by a thread, Streisand belted out the songs that raised the money that elected the senators that stopped Robert Bork's appointment to the Supreme Court. When measured against all other celebrity icons, history will judge that Barbra Streisand used her gigantic fame, wealth and power to fight for justice. She not only sings proud, she thinks and acts proud.

End.

Barbra Streisand Remembers JFK Jr.

Originally Posted: July 27, 1999 at BJSMUSIC.COM

(reprinted with permission by Mark Iskowitz)

Barbra Streisand's publicist conveyed the following comment from Barbra regarding the tragic death of John Kennedy, Jr. “Jim and I extend our deepest sympathy to the Kennedy and Bessette families on this tragic loss of such vital, talented and lovely young people. John had brought a new verve to magazine publishing and to the political dialogue, and he will be missed for his decency and commitment.”

Barbra was featured significantly in the pages of John Kennedy's George magazine three times. First, she was among the “20 Most Fascinating Women in Politics” profiled and interviewed in a September 1996 issue. Next, she was the magazine's cover story subject in November 1996 (see above). In its March 1999 issue, George printed Barbra's letter to the editor responding to magazine criticism of her November 1998 America Online chat urging people to vote, especially for Democratic Party candidates. [You can read that here]

Making the Cover

An excerpt from Matt Berman's book about his time working with John F. Kennedy Jr. on George magazine was published in the June 2014 issue of Vanity Fair magazine. Although the article “dished” on celebrities (including Streisand), there were some interesting factual details in it about Barbra's cover shoot with Firooz Zahedi for George. Berman wrote:

****

I told her that Betsy Ross would be a great character for her, how we’d execute it perfectly. Then I suggested a photographer to take the photos. She agreed and said it would be easier to shoot at her house in Malibu than at a studio.

[...] The shoot was elaborate. We’d hired the costume people who had done the gowns for Dangerous Liaisons, and we’d gathered flags, thimbles, threads, pincushions, and fabric stars as props for Barbra’s transformation into Betsy Ross. Debating possible background choices, we looked at cloth backdrops that the photographer had brought. One was authentic for the period but dull and brownish. However, it was pure Americana, and I knew Barbra would love it. We set up the shot in a small guesthouse, where Barbra edited her movies. It was the original house on the property. The photographer and his assistants, the hair, makeup, and prop people, stylists, publicist Ken Sunshine, manager Marty Erlichman, Kim the assistant, John, and I all crowded into the room.

[...] Barbra wriggled into lots of different poses on the Revere sofa. It became apparent to me, watching her move as the camera flashed furiously, why she was a star. It was impossible to take your eyes off her. She saucily pulled her skirt up to display her garters and bloomers. She coyly pulled fabric stars from her cleavage, saying, “Oy, what are these doing here?” Next, she cut some stray threads with her teeth. “Oh, that’s some thread!” Then she took one long stitch through the flag, flashed a long-awaited Fanny Brice smile, and said, “This is going to be one hell of a flag, boys!”

Below: Firooz Zahedi's unedited photo of Streisand as Betsy Ross.

End.

[ top of page ]