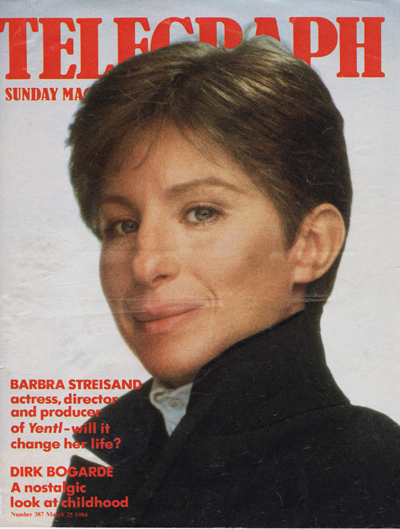

Telegraph

March 25, 1984

This magazine was contributed to Barbra Archives by the David Salyer Collection Courtesy of Joseph Goodwin.

Barbra Streisand’s house in Los Angeles bears a certain resemblance to Sleeping Beauty's castle in Disneyland, except that it is less accessible. The road outside is deserted: a small camera by the side of the driveway scours the vicinity for cars and scrutinises every caller seeking entry. A high wall conceals everything except for a glimpse of dense greenery. When the gate finally opens it turns out to be a huge sliding wall which draws . slowly back. It is an announcement in itself. There is nothing welcoming to the outsider here. This is a private kingdom. It is sometimes said that Barbra Streisand is America’s biggest star.

Barbra Streisand’s house in Los Angeles bears a certain resemblance to Sleeping Beauty's castle in Disneyland, except that it is less accessible. The road outside is deserted: a small camera by the side of the driveway scours the vicinity for cars and scrutinises every caller seeking entry. A high wall conceals everything except for a glimpse of dense greenery. When the gate finally opens it turns out to be a huge sliding wall which draws . slowly back. It is an announcement in itself. There is nothing welcoming to the outsider here. This is a private kingdom. It is sometimes said that Barbra Streisand is America’s biggest star.

It is also said that any film in which she appears automatically makes money. Down the road, in Westwood Village, her new film, Yentl, is playing in the Fox Village Theatre. Outside is the poster of which she had total control — and all the more revealing for that: it is of a face as a work of art, frozen, stylised, quite beautiful and in soft focus. This face of Streisand leaps from the poster; more effigy than photograph, there to be admired. Across the street, Terms of Endearment is playing at another cinema. Shirley MacLaine and Debra Winger, its stars, are shown on that poster gossiping on a bed, hair awry, legs kicking idly. It creates the impression of a snapshot: a moment of life and vitality.

The audience has made its preference known. Yentl, written, produced, directed by and starring Barbra Streisand, who sings all of its songs to boot, was released in the U .S. two months ago. It has taken 30 million dollars at the box ofiice. Terms of Endearment, released at the same time, has taken well over twice as much. This discrepancy gives a clue to why Miss Streisand is available to be seen and interviewed, usually a difficult process.

Her town house is set in the hills above Sunset Drive. It is surrounded by trees, plants and lawns of rich, deep green. Only endless nurturing could create such glades and gardens on this one-time desert. Such peace and isolation is seen as the greatest luxury in Los Angeles. It seems ironic that the ultimate in life should be the quiet of a graveyard: it is not an entirely irrelevant thought, as it turns out.

To one side there is a small cottage. The door stands open. Inside, behind a large desk laden with tapes, film, scripts, notes and notebooks, sits Streisand’s personal secretary, Kim Skalecki, young and pleasantly ordinary-looking. But Miss Skalecki is no ordinary secretary: how could she be when she controls access to a star of such order?

Mail, telephone calls, messages, everything must go through her; everything rests on her slight shoulders. She lives in the cottage, stays at her post as long as she is needed, and talks of what “we are doing”, of “our projects”, and of people “who are involved with us”.

She is also guardian of the filing cabinets lined up next door. Streisand’s filing system has always been talked of with awe in the industry. Even if it does not contain notes and judgement on every film-maker and technician in the land, its reputation for doing so tells much of how her colleagues view Streisand Superstar.

Some actors go out on the set and play their scenes. Streisand has always been notorious for caring about every detail both of her business and everyone else’s. Yentl, her directing debut, is therefore the logical conclusion of this need to know everything and to control. everyone. “Directing”, she says later, “is the perfect job for me. Everything I’ve ever learned my whole life comes into play”.

It is Friday afternoon, a time when Los Angeles is planning its weekend. Miss Skalecki, keeping one eye on the road outside, blurrily captured on the screen beside her and the other on visitors holding a meeting in a corner of her cottage, is also telephoning around to find some of Streisand’s friends who might like to come over and watch movies on Saturday night.

The day is warm, the room stuffy. A move towards the garden door draws Kim’s immediate attention. “What are you doing”? she snaps. “There's a dog out there”. A Doberman stretches out by the white picket fence near the blue pool and orange trees.

At the other end of the room, opposite this door, there is a small photograph of Streisand with John Lennon and Yoko Ono. There is the point: she can no longer feel safe.

“I don’t go to concerts”, she says coyly, “because I don’t want to have to keep singing People”. She gave one charity concert — for Israel — in Los Angeles a while back: the backstage staff had never known such security.

When she was young and unknown in New York, a friend points out, she slept anywhere. She lived alone and was never afraid. How different it is now.

There are photographs all over Kim’s walls. Here is Barbra with lsaac Bashevis Singer, the Nobel prize-winning author of Yentl. Streisand bought the rights to the short story from him 15 years before being able to make the film. It would be a mistake to think that he is grateful for her tenacity.

“I must say”, he wrote of the film in The New York Times, “that Miss Streisand was exceedingly kind to herself. The result is that Miss Streisand is always present, while poor Yentl is absent“. Worse was to come. “The whole splashy production”, he finished, “has nothing but a commercial value”.

It was the most spiteful cut. Who else but Streisand, this strange, driven and powerful star, would have made a film about a rabbi's daughter in I904 Poland; about Yentl, with “the soul of a man and the body of a woman”. The smell of herring and repression are of no commercial value to the film business; Understandably, six studios turned it down.

Yentl is Streisand’s love letter to a religion that she was never allowed to forget, even in the years when she might have been tempted to do so. She settled in Los Angeles, after all, only after being turned down twice as “unsuitable” for smart apartment buildings in New York. "I got very angry at that city”, she has said. “I was turned down because I was an actress, or because I was Jewish, or both. l took it very personally, to tell you the truth”.

The history of her journey to Sunset Drive from that first, small home in Pulaski Street, Brooklyn, is written in the photographs in the elegant mansion she has earned and created. “I lived with my mother, who had newspaper on the floor so it shouldn’t get dirty, and crappy plastic covers on the furniture so it wouldn’t get stained. Where’d I get this appreciation for fine things? I don’t know. I just got it".

Over there is a photograph of Barbra with her mother and half-sister at the opening of Yentl. Her mother, plump, out of her element; the half-sister, who was always thought to be the pretty one as a child. Behind both is the star — faultless, imperial. Those early years in Brooklyn have been avenged: the gawky, ugly, skinny Miss Streisand has proved her point. The mother who discouraged her acting (not attractive enough to look at) and her singing (too weak a voice) must recognise now who is the patron.

The photographs span over 20 years of being successful. In 1961 she stole the show in I Can Get It For You Wholesale, as Miss Yetta Marmelstein; and two years later she married its leading man, Elliott Gould.

In 1968 she was co-winner of the Oscar as Best Actress with no less than Katharine Hepburn (Hepburn for Lion in Winter, Streisand for Funny Girl). There have been Oscars, Emmys, Grammys, 33 albums and 12 films since then. She played opposite Robert Redford, Hollywood's favourite WASP, in The Way We Were. She has had it all.

But years ago, soon after they separated, Elliott Gould said: “If Barbra conquers the world, if every last person in it says ‘Barbra Streisand, you are the most beautiful, intelligent person, the greatest’, it will be the saddest thing for her. Finally she is going to be left with herself”.

It does not escape notice that on these walls are few photographs that are not about Barbra. Most are of her face: one which has undergone such changes over the years that it looks as if it belongs each time to another woman. Other people appear here only in relation to her: a small child, tousle-haired, black-eyed, is held in her arms.

Only very few shots of him, though; it is not his history. He is her only son Jason, 17, now glimpsed flitting through the cottage in his dressing-gown.

In the main house, in an airy room decorated entirely in white, Barbra Streisand, born-again nice person, is trying to be charming under difficult circumstances. It is hot, it is late, she has been on the telephone for hours; she resents having to be on view. She is 41 years old and would like to feel that she has earned the right not to justify herself.

“You see pictures in the paper of Jackie Onassis or Elizabeth Taylor; they're always smiling like ladies. You see pictures of me, it’s like, you know, leave me alone, get outta here, why are you taking my picture? l resent being treated like a thing, a commodity, an image. l don't think l’ll ever get used to it”.

It is, of course, largely of her own doing. She has always controlled everything about herself, as if she were marketing a commodity.

In America everyone gets the press they deserve.

But Streisand says she has grown up; directing Yentl was, “My joumey into adulthood”. As she was her own director there was no one to fight, no one to say “No” to her — but no one to turn to either. “I couldn‘t be the child any more. I had to be my own father and everybody else’s mother”.

Amy Irving, who plays Hadass, the embodiment of passive femininity, talks of Streisand as director: “She’d fix my hair ribbons, brush an eyelash ofl' my cheek, paint my lips to match the colour of the fruit on the table. I was like her little doll that she could dress up”.

This remark comes to mind now as Streisand talks of her early life in Brooklyn: “I didn't have any toys to play with. All I had was a hot water bottle with a little sweater on it. That was my doll”. There was the beloved father who died when she was 15 months, the mother who was left destitute and went to work — and the child’s anger that survived for years at being abandoned by both, as she saw it.

Now she says that Yentl has changed everything. “I was in such pain before, so confused about myself. I had a lot of self-pity, too, but that’s gone now. I’m finally at a point in my life when I feel much more compassion for others, much more forgiveness”.

For financial reasons the film had to be made in London and Czechoslovakia. It meant being away from Los Angeles for over a year. That triggered her separation from Jon Peters— the producer of A Star is Born, Missing and Flashdance — with whom she had lived for eight years. Life in London was different: she was more free and when she went out no one followed her. In fact, seeing her in jeans and frizzy curls, it is unlikely that anyone recognised her.

“Anyone who meets me for 20 minutes”, she says at one point, “knows that I’m just a regular person”. In a way it’s true. It is the mystique which imprisons her, not the presence. She is neither grand, nor formal.

She still has a Brooklyn twang, a streak of quick humour and vulgarity. She is dating, she says, and going to courses on the psychology of the differences between men and women. She goes to both the University of Southern California and the University of California at Los Angeles to study and is trying to decide to which of the two she will give half-a-million dollars for a Chair of Women’s Studies.

She has already given that amount to UCLA to endow the Streisand Chair of Cardiology, dedicated to the memory of her father. Yentl, too, is dedicated to her father.

Jon Peters has said of the film: “Barbra created her own father on film so she could love him and say goodbye to him. She buried her father in the movie”. Certainly when, in 1979, she went to see his grave for the first time, he came alive for her and she grew to love his memory and forgive his death.

Even now, though, the resentment at what life has done to her keeps poking through. “I never learned to manipulate men”, she says. “Because you don’t learn feminine wiles from women. You learn them from men. You learn them from the Daddy that you can run up to at the end of the day and throw your arms around, and the next day he buys you a new dress.

“I went to work at 18”, she says. “I never had the time, or the inclination, for just having fun. I don’t know quite how to have human contact. l know it means meeting with new people and getting interested in other people — I'm ready for that: I'm not enough for me any more”.

As the great moving wall clangs shut at dusk there is a sense of relief. The cage inside that wall may be gilded well, and softly padded, but it is stifling in there.

END.

Related Pages: Yentl movie page