Sunday Times

March 4, 1984

Streisand's New Direction

by Jeannette Kupfermann

At first it seemed like an odd partnership, an uneasy alliance. But Barbra Streisand, after going through a stream of cowriters, decided at last on Jack Rosenthal (Barmitzvah Boy) to work with her on the the script of Yentl. Jack with his beautiful spareness; Barbra with her penchant for the florid and baroque. A surprising collaboration indeed. But a successful one.

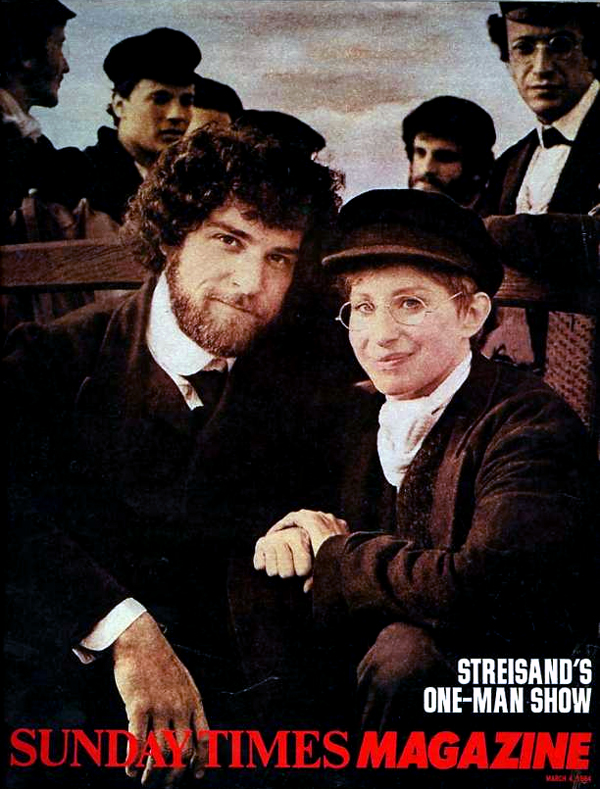

Yentl is the Isaac Bashevis Singer story of an orphaned girl from a traditional Jewish background who rejects her femininity and disguises herself as a boy to enter the exclusive male world of learning, only to fall in love there.

Streisand was first attracted to notion of it in the late Sixties, when she saw it only as the ideal vehicle for her acting talents. But in time the visual aspects caught her imagination. In 1974 she bought the rights to the Yentl story. She would not only star in the film, but she would script and direct it as well. It's easy to see the appeal for her of a story that strikes deep into her Jewish roots. It touches off feminist feelings, too, in that it tells of a woman who, uncertain of her role, eventually finds herself. Then —and perhaps most of all — there was the transvestite element. Barbra can look surprisingly boyish and winsome in male costume.

A 40-year-old actress, she had tried most other things. This offered new depths. Barbra sees herself as having inherited the scholarly interests of her father, a teacher, who died when she was 15 months old. She thinks of herself as continuing his quest for knowledge. The film is dedicated to him and is very much an expression of this.

And it had to be right. Authenticity was paramount. To that end, we went together to a Hassidic wedding in New York to observe the elaborate rituals. It was a wet, chilly evening and she'd had a hard day casting supporting actors. There was scarcely time for her to powder the celebrated Streisand nose.

And it had to be right. Authenticity was paramount. To that end, we went together to a Hassidic wedding in New York to observe the elaborate rituals. It was a wet, chilly evening and she'd had a hard day casting supporting actors. There was scarcely time for her to powder the celebrated Streisand nose.

During the drive through the rain beyond Brooklyn Bridge, a jittery Barbra huddled in the back of the limousine. John Lennon had just been shot. Perhaps she was frightened. “Did you know that nut is still phoning me?” she complained.

But at the wedding she was excited by the colourful ceremony, which included the bride walking round the bridegroom seven times. Intrigued by the faces of the old men and the young children looking on, she would exclaim, “Gee, I'd love him in the film, he's cute.” The bridegroom was also "cute" but when the bride removed her heavy veiling, Barbra made a face and nudged me, whispering loudly, "God, she is ugly!"

After watching the black-hatted men dancing at the reception in their long snake lines, hands on shoulders, she danced herself, with a shy, slow, deliberate grace, with the women in one of their circles. She was wearing black thigh boots and slit skirt. The bride danced, too, but there could be no doubt who was the star.

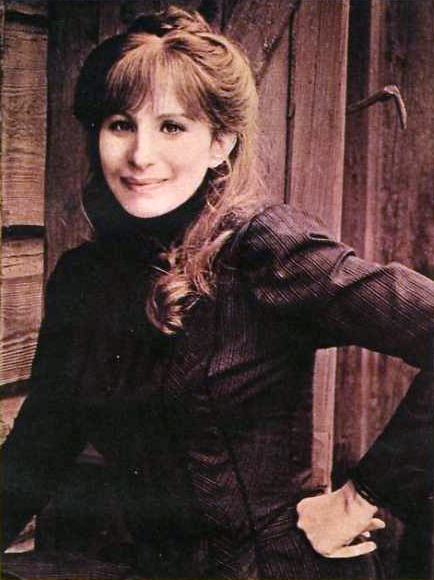

Barbra uses clothes to project her mood: black signals glamour and authority; in white she comes the little girl lost; anything in between (usually maroon and beige) registers a neutral working image very much the detached director.

As an actress performing within her film, her sense of "rightness" was infallible. I remember watching her blocking out one of her songs, dressed in quasi-Yentl costume (expensive suede "peasant" skirt with a silk blouse and waistcoat), and hair up in the Edwardian "onion" which suits her skinny face. She would try all kinds of stances, while she mimed with her graceful hands, instinctively knowing when to shift position by half an inch. "Could we just try it with my hand brushing my face?" she would insist, checking it on the video.

My own involvement with Yentl had started when I asked to do some research on the picture. Since then I had been kept busy ("Barbra would like you to do this, find that . . .") but a meeting with the woman had eluded me for three years, until I called at her hotel room in London's Park Lane.

I was taken aback when Barbra herself answered the door small, pale, frizzy-haired. She looked tired and, without makeup, quite old. But the puckish quality was there in the strange, slightly crossed cat's eyes and the sensitive, curly mouth. The only concession to filmstar "glamour" was the long fingernails of an extraordinary length, curving like talons, and carefully lacquered a natural shade. One or two had broken, and I noticed bottles of Nailfix and other such emergency repair kits scattered around the room. "My mother wanted me to study typing," is how she explains it, "and I let my nails grow long so I couldn't type. I didn't want to end up a secretary."

Barbra was messy. Flung all over the place were scripts, photographs, camera equipment and other paraphernalia.

Other colleagues sat around on velvet couches— the stray producer, agent and assistant art director— staring into space or at a makeshift screen on which flickered 8mm-film of Streisand shot recently in Prague.

A huge round table was wheeled in, piled with hamburgers, sausage and mash, bottles of Coke and coffee. Barbra herself had ordered a steak which looked huge and unappetising. "Here," she said, cutting off half, "you take some." She then proceeded to eat from everyone else's plate greedily and with glee.

Food for her is a way of being intimate. She doesn't only eat substantial amounts herself (in spite of the weight which goes straight to her waist and face, with 5lb. more or less making all the difference to her cheekbones), but insists on sticking food into other people's mouths and on to their plates. Once, in a Chinese restaurant, too, she kept urging me to eat, then said with a mischievous smile, "We cleaned our plates good, huh?"

She will break out of her diet to binge on half a dozen cream cakes. It became hard not to think of food on Yentl, with mountains of it being brought in daily from Bloom's and left decadently lying about on the set.

I had heard about Barbra's Art Deco house in Hollywood where visitors are each given different colour slippers to put on, depending on their personality. There was nothing to equal this in England, where her "home" had to serve as an extension of the studio and office, providing enough telephones, cupboard space for her own film equipment and extensive wardrobe, intercom systems, and a must enough bathrooms. She did, however, find a house in Chelsea which plainly delighted her, though it was only a disappointingly short let as it belonged to Rod Stewart's former manager, Billy Gaff.

I had heard about Barbra's Art Deco house in Hollywood where visitors are each given different colour slippers to put on, depending on their personality. There was nothing to equal this in England, where her "home" had to serve as an extension of the studio and office, providing enough telephones, cupboard space for her own film equipment and extensive wardrobe, intercom systems, and a must enough bathrooms. She did, however, find a house in Chelsea which plainly delighted her, though it was only a disappointingly short let as it belonged to Rod Stewart's former manager, Billy Gaff.

During the working day, the phones rang incessantly. There were about six of them, even one in the bathroom. She rushed from room to room, denied no one, speaking to her mother, the costume, designer, the chauffeur ...

I caught snatches of conversation about getting together her son Jason's ski clothes. Barbra is quick to counter to any suggestion that she may not be the world's most dedicated mother, though she told me that she didn't find it easy to bring up one child, let alone contemplate having any more.

Barbra has produced other films but Yentl is the first she has directed.

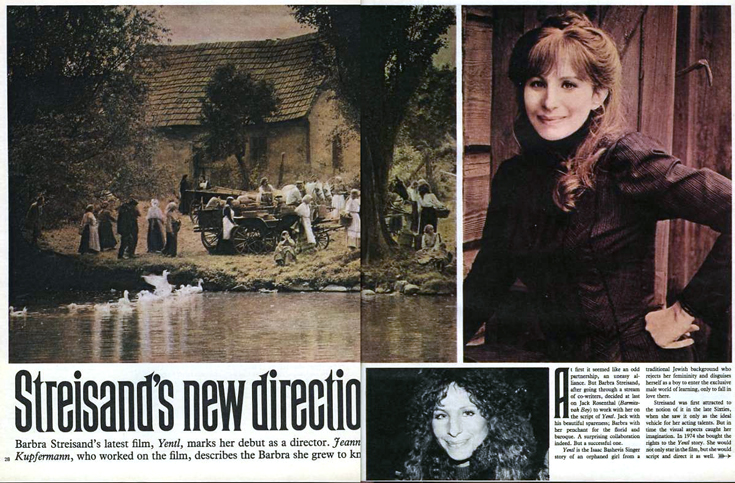

She had a quiet, unostentatious way of working — no megaphones, no flamboyant directions, all very low key. But then, much had been worked out in advance, and she had a brilliant director of photography (David Watkin) and cameraman (Peter MacDonald), as well as Roy Walker's eye for realism. Later there would be those who would say that she didn't so much direct (in the manner of a Fellini or a Bergman) as edit. "She always knew a good idea when she saw one, though she rarely originated one," was the verdict of one colleague. But Barbra insisted, "I had visions in my head, I knew exactly how I wanted it to look."

Her obsession with "the detail of the detail" sometimes led to disagreement. Although she had a firm idea of how it all should look, she was not always articulate enough or, as she said, was "too embarrassed" to confront someone else, particularly if that someone else was a creative artist with a considerable reputation.

Instead, she would let them do it their way, only by her silence expressing a certain doubt, and it would end up on the cutting-room floor. It was thus with Cats choreographer Gillian Lynne. Gillian produced a ballet sequence when Barbra wanted a few simple movements but then, she hadn't made that clear, and as a first-time director, she too was learning as she went along.

And if on set she was humble, quiet, not obviously authoritarian, power was nonetheless being exercised. "I was frightened of so much power," she admitted, "so I tried to appear unpowerful."

One close colleague said of her, "Barbra has the belief that people who have been paid for don't need stroking, which isn't true at all. She will reach out to people when she's desperate, but as soon as that's gone, they don't exist any more. You can measure your usefulness to Barbra by the Christmas presents you receive. Mine have definitely got smaller."

Again, though, there are several people (usually men) on the film who felt they had a "special relationship" with the star only to discover, after the completion of filming, the temporary and functional nature of that relationship. She does have the ability to make one feel "special", reinforced by her air of concentration and her intense questioning. She can focus that attention like a beam then just switch it off.

She was very much an actor's director, according to those who took part. "She would let you try all sorts of things, partly out of nervousness of directing for the first time," said Allan Corduner. "Of course she had her good days and her bad days when she was more distracted. She's a very private person, and perhaps you do have to be a little more outgoing to direct, but I think everyone enjoyed working with her."

She uses a lot of advisers and her main way of educating herself is by asking questions. "Have you found out about plaited candles?" she'd ask and, before you had time to answer she would go onto ask something else.

She uses a lot of advisers and her main way of educating herself is by asking questions. "Have you found out about plaited candles?" she'd ask and, before you had time to answer she would go onto ask something else.

At home she would have long nightly telephone conversations with other directors and advisers —people in command of knowledge she wanted. Hers was not the cautious "scholar at the feet" approach, it was Brooklyn straight-up-front, "I wanna know..."

The final version of Yentl lost Singer's sense of mischief and lurking demons, and became more the story of one woman's quest for knowledge, love, and herself. "It's really a film about a woman's growth," Barbra told me. It became an uncanny translation up there on the screen of a difficult searching, troubled woman— Streisand herself —given a kind of overall unity by the music of Michel Legrand. The final script was approved by United Artists who eventually bought the property, which cost $16-1/2m to make.

A lot of old film-school processes were used— Super 8, video, small tape recorders, informal readings, and colour video tape, with Barbra in costume — until a mini-version of the film was put together, and they could see to all intents and purposes a rough cut of the film. So that Barbra could experiment with the muslin before cutting the silk.

In the beginning, "Barbra was a real amateur," Roy Walker admitted, "but she learned how to do things very quickly."

According to her producer, Rusty Lemorande, Barbra's sound instincts as an actress held her in good stead.

"What I thought was Barbra being a good director was in fact Barbra being a very talented actress. Barbra had the sense to know a good idea when she saw one, and that's what we're talking about the ability to be in touch with one's instincts. Yentl itself is about 'Don't tell me I can't. I'll show you I can.' And that's how it is with Barbra."

Streisand has become a multi-million-dollar industry but she remains a surprisingly lonely and fragile woman. I was to glimpse her vulnerability again and again. Her eggshell thin skin was most apparent in moments of extreme tension or panic, which mounted as the film neared completion.

Her worst tensions were about her role as director and she had been known to be physically sick in the car on the way to work. "I was worried I couldn't do it," she told me. "That's why it took 15 years."

On set her calm was deceptive. In between takes, surveying herself in the full-length costume, the tension would show: dark shadows and swellings would appear under the eyes and makeup man Wally Schneiderman would be summoned to work wonders with brush and white shadow eraser. "Jeez I look awful" could be heard again and again.

I last saw her for lunch in the Chinese restaurant next to the EMI studios where she was putting the finishing touches to the dubbing. Again she wore white— the little girl, mid-summer white of a mini-dress, and matching tights —again, a little bit at odds with her face. But then Barbra, recently on the World's Worst Dressed List, in her own clothes, often manages to look slightly incongruous; the exaggeratedly wide shoulders, the slightly too long or too short skirts; the tottering heels the woman perhaps who, like Yentl, can't quite accept her own womanhood.

My lasting impression of her is from the night of the first preview of the finished film. Inside the Elstree preview theatre, the invited audience rose to their feet and applauded as the long fist of credits appeared on the screen. Some of the women dabbed at their eyes: most were visibly moved. The predominant feeling seemed to be one of relief that a 15-year-old impossible dream had finally made it up there to the screen after many stops and starts, and Barbra had finally done it. But where was she? People looked round to see her, but she was nowhere to be found. I left the theatre and went out on to the dimly-lit backlot, where I saw a light coming from one of the stage doors and, huddled behind it in the shadows, a small figure in black.

Barbra, face drawn and white, hair in a wispy ponytail, saw me and said nothing for a few seconds. Then she reached for my hand and went on holding it, asking tremulously "Is it all right?"

It's a question every woman asks after giving birth.

End.

Thanks: to Allison Waldman for contributing this article.

[ top of page ]