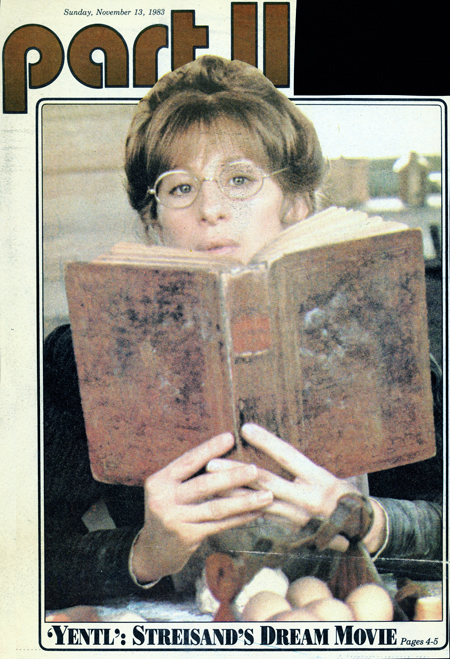

For Streisand A One-Man Show

Part II

November 13, 1983

By Jerry Parker

“Yentl” was a 15-year quest for the actress, who starred, directed, produced, cowrote and sold it to a skeptical Hollywood.

TWENTY YEARS of super-stardom ought to take a toll, but Barbra Streisand is looking slim and girlish and buoyant. At 41, Streisand has smooth skin, soft blue eyes that dance with energy and, at least during her recent Manhattan visit, enviable high spirits.

Though she has been known to greet interviewers with the look of one who has a gun to her head — and has avoided them for years — on this trip the actress seems absolutely enthusiastic about the prospect of meeting the press. The difference is the subject she is most eager to discuss, “Yentl,” her first movie in two years and the film project that has been her consuming passion for 15 years. It will open, finally, Friday: produced by Barbra Streisand, cowritten by Barbra Streisand, directed by Barbra Streisand and starring Barbra Streisand.

She is “the first woman in film history to produce, direct, cowrite and star in a major feature,” according to the film’s distributors, MGM/UA. On this day in her Park Avenue hotel suite, the pioneering woman film maker is wearing a bulky, multicolored sweater over black tights and suede boots. Her golden-brown hair hangs in frizzy ringlets around her face. When the room service cart arrives, Streisand attacks her eggs benedict with hang-the-calories zest and, between bites, speaks excitedly about “Yentl.”

The film is based on "Yentl, the Yeshiva Boy,” a 15-page short story by Isaac Bashevis Singer, the 79-year-old Nobel Prize winner. It has already inspired a play, which came to Broadway in the mid-’70s with Tovah Feldshuh in the title role. It is the story of a Jewish girl in turn-of-the-century Eastern Europe who yearns to study the Talmud, an activity forbidden to members of her sex.

But Yentl’s thirst for knowledge is so great that she disguises herself as a boy, assumes the name of her dead brother — Anshel — and enters the yeshiva of a neighboring city. Yentl/Anshel falls in love with Avigdor, a fellow student played by Mandy Patinkin, and, in a complication that is positively Shakespearean, finds himself/herself married to Avigdor’s intended, Hadass (Amy Irving).

Streisand first read “Yentl, the Yeshiva Boy,” 15 years ago when a friend sent her a collection of Singer’s short stories. It made a deep, and immediate, impression.

“The first four words of the story are ‘After her father died . . .,’ ” the star recalled. “So it grabbed me immediately, because I was always the little girl on the block with no father. I was always different because everybody else had one and I didn’t.”

Emanuel Streisand died of a cerebral hemorrhage at 35, when his only daughter was 15 months old. He was a teacher of juvenile offenders in Elmira and wrote his doctoral dissertation for Columbia Teachers College on the works of Dante and Shakespeare. He is buried in Queens, where his tombstone bears a Phi Beta Kappa key and the words “beloved teacher and scholar.”

Streisand visited her father’s grave for the first time when she was struggling to bring “Yentl” to the screen. “Next to his grave was another tombstone,” the star said with a soft smile, “and on it was the name ‘Anshel.’ It was like he was guiding me, telling me to go forward, have courage.”

Streisand refers to her film as "a poem to my father” and the closing credits of “Yentl” dedicate the film “to my father, and to all our fathers.” While the film was in production in London and Prague and the tiny Czechoslovak village of Roztyly, the director/star occasionally felt her father’s presence.

“I sometimes would quietly ask my father for a sign,” she said. “One gray day, when I was being pressured to film when I didn’t want to — because it wasn’t the right light — I said ‘Poppa, tell me what to do.’ All of a sudden, it started to rain, which forced the decision, which was to work inside and not try to film in the gray light.”

If the star received some encouragement from beyond, she received shockingly little in this world. “No one,” she said with a tone of triumph, “wanted to make this picture. Fifteen years ago, a director told me I was too old for the part. I was 25 years old!”

In Singer’s story, Yentl is 18, but Streisand and her coauthor, Jack Rosenthal, have made her an “old maid” in her late 20s who has the locals clucking about her unmarried state. In her male disguise, the middle-aged actress looks amazingly like a downy-cheeked youth. Streisand thinks her disguise makes her look like her 16-year-old son, Jason, the child of her marriage to actor Elliott Gould.

The star was also told, repeatedly, that “Yentl” was “too ethnic” to be a commercial success. Rejections came from studios for which Streisand films had made hundreds of millions of dollars. Warner Bros., where Streisand made “What’s Up, Doc?,” “A Star Is Born” and “The Main Event,” wasn’t interested; neither was Columbia, for whom she made “Funny Girl,” “Funny Lady” and “The Way We Were.” The most bankable female star of them all had been constantly reassured that she could film “the phone book — as long as I sang a couple of songs.” Since “Yentl” was to have an extensive score by Michel Legrand and Alan and Marilyn Bergman, the rejections were something of a shock.

“It was a wonderful kind of shaker-upper,” said Streisand, “realizing my own lack of power. They were frightened of it because of the background being Jewish, frightened of me as a woman, directing and starring. They probably felt I’d go way, way over budget.”

The star found herself in the humbling position of having to hustle her project to moguls all over town. “It was fun for me,” she declared, “it was like being 18 again, saying, ‘Hey, I’m a good actress, try me out, give me a chance.’ It gave me enormous drive. Every time they’d turn me down, I’d' say, ‘How can they do this? How can they not see the beauty in “Yentl?”’”

At one point it seemed that Jon Peters, Streisand’s longtime companion, would come to her rescue. By then a partner in Polygram, Peters assured her the company would produce “Yentl.” “Then,” said Streisand, “we started arguing and fighting. I said I wanted to talk to Assaf Dayan about playing Avigdor. He said, ‘We won’t make the picture with him.’ I said, ‘I can’t even talk to him?’ So, I decided no way can I be in that position, and I took it away from the one person who would make it.”

Though Streisand says she and Peters are still very close, they no longer live together. In recent months, gossip columns have linked her name with that of both director Steven Spielberg and Canada’s Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, but Streisand describes them both as “good friends.” Other friends say she has been much too absorbed in “Yentl” to embark on a new romantic entanglement.

When United Artists finally agreed to finance “Yentl,” Streisand’s love of the project was well- known and she was not in the most advantageous negotiating position. She took no money for cowriting the screenplay, and only Directors Guild scale (about $80,000) for directing. Her salary as an actress was less than the $4 million she reportedly received for “All Night Long,” the 1981 box-office failure that costarred Gene Hackman. Streisand even promised to forfeit half her salary if “Yentl” went over budget. It did (by 11 per cent, coming in for about $16.5 million), and she did.

Though Streisand will still take home well over a million dollars for her work on “Yentl,” the project was clearly not about money. “Yentl had a dream and pursued it,” said Streisand, “and I had a dream and I pursued it against the odds. Yentl says ‘Nothing is impossible’ and I believe nothings impossible. I believe we can do anything we want if we put our minds to it.”

The determination she brought to “Yentl” recalled for Streisand the dream she had as a father-less child back in Brooklyn. “When I believe in something,” she said firmly, “I believe it to the bottoms of my toes. I’ve lived through this story before. When I first started and I was singing Harold Arlen songs in nightclubs, I didn’t dress in sequined gowns, I wore antique clothes, because I believed in the beauty of those clothes, I believed in the beauty of those songs.

“I believed in my name, you know. They said, 'Don’t you think you should be Barbra Sands or Barbra Strand, and maybe have your nose done?’ I thought, why would I have my nose done, why would I change my name? I can’t change me and make me into something people think they want. I know what they want is that which is truthful and passionate, that is the only thing that transmits itself, that stands the test of time.”

By those standards, “Yentl” is a worthy achievement: The star’s passion for the subject, her love of the character, is stamped on every frame. The critics have still to be heard from, but the self-critical, perfectionist director and star is content.

“Life is a compromise,” she said, “nothing is perfect, and I still potchkeh with the sound, I potchkeh with the color, but this is pretty much the ‘Yentl’ I saw in my head. I am very pleased.”

Beyond “Yentl,” Streisand wants, first of all, “a long vacation.” Further in the future, she wants to write a book, “do the classics I’ve always wanted to do: Shakespeare, Ibsen, and Chekhov” on television, and go to college.

“If my father had lived,” she said, "I would have gone to college, and I am my father’s daughter.”

What we are not likely to see, anytime soon, is Barbra Streisand standing up before a live audience singing Harold Arlen songs. “I have stage fright,” she said with a shrug. “I have a fear of crowds, of forgetting the words.” Oddly, it is a fear that has grown with time.

“Maybe the more success you have the more you have to lose,” Streisand mused. “The more people admire you, the more you’re afraid to disappoint them. For being as famous as I am, I really lack self-confidence in many areas.”

An actress who produces, directs, writes, and stars in a film no one wanted to make ought to be able to muster the self-confidence to sing in public. There is hope. “I want to conquer my fears,” said Streisand, and, as Yentl and she both know, nothing is impossible.

END.