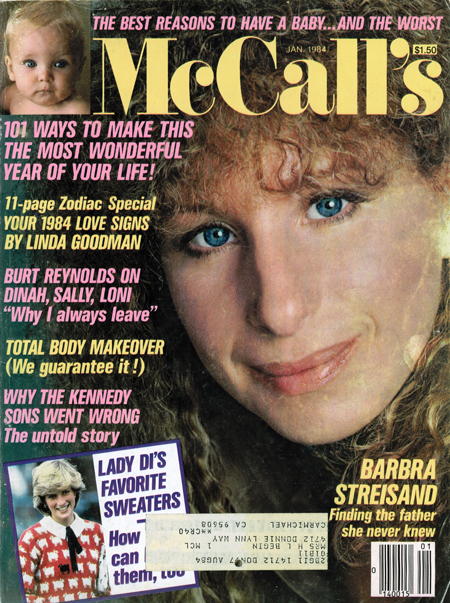

McCall's

January 1984

Barbra Streisand

Finding the father she never knew

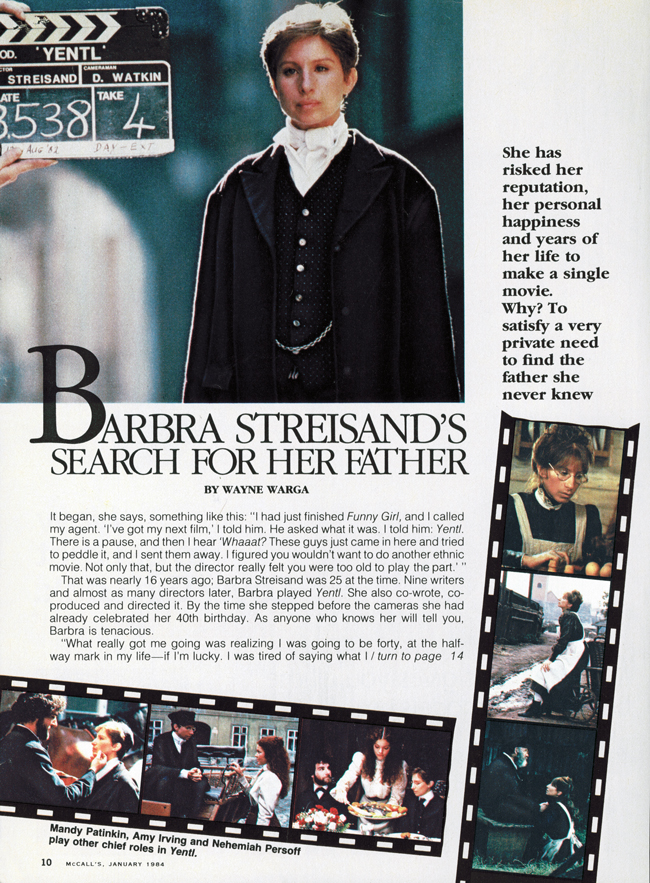

by Wayne Warga

should do, or saying, ‘If I had more courage, I’d do that.’ It was time to put up or shut up. I finally realized that I had to tackle it. I wanted to take the full responsibility for its success or failure. I could no longer blame anyone but myself. There is no cop-out on this one.”

She pauses and takes a sip of tea. “It isn’t an ethnic story. It’s a story about the triumph of the human spirit. It’s about people. It’s a story about love. You don’t think it’s ethnic, do you?”

For just a second, the Streisand insecurity appears. It is a devil with which she wrestles constantly. She is a questioner, a doubter, a woman who is prone to answering questions with questions of her own.

Yentl, based on an Isaac Bashevis Singer short story, tells the tale of a young Jewish girl in Poland during the early part of the century. As a female, Yentl cannot go to a Hebrew school and learn the great lessons of her religion. But her father, who understands her love of learning, teaches her anyway, and when he dies she goes off to school on her own, disguised as a man named Anshel.

“Sometimes when people ask me what the movie is about, I don’t really know quite what to say,” she admits. “It’s about a lot of things. It’s about taking chances. It’s about taking risks. It’s about growing. It’s a love story about learning. It’s a love story between parent and child. It’s a love story between a man and a woman. Ultimately, it’s a story about the love one must have for oneself.”

Not only is it all of that, it is also a period film and, as its star, co-writer, co-producer and director emphatically states, “It is a film with music. It is not a musical.” One wonders if it might not have been easier to pick a somewhat less complicated, more contemporary story:

“Who me? Do something easy?” The crack is vintage Streisand, pointedly rhetorical, Brooklyn-accented and self- deprecating. She is not the quipping fast talker from her movies now but a quiet, committed and—well—worried woman. Yentl is being shown on a limited basis, but it has not yet been released across the country, and she is now wondering if, after 16 years, she can give up her obsession.

“To me, the most creative experience I’ve ever had was being pregnant. This is the second most creative experience: directing a film. It is all a very strange feeling. When my son was inside my belly, he was only mine. As soon as he was born, he belonged to the world, he was his own person. It’s the same thing with this movie. In a way, I wish I never had to show it.”

She is in her house in Holmby Hills, part of a small community near Beverly Hills. The house is—like almost everything in her life—exactly as she wants it. It is a reflection of her love of Art Deco. She is sitting on the sofa in her small study, a room whose dominant color—from the piano to the desk to the sofa and chairs—is white. And she is listening, pondering every question. She rarely gives interviews—preferring, she says, “to let my work express my feelings and my thoughts. I’m not good at this sort of thing. I don’t feel I’m eloquent or articulate. Besides, so much has been written about me that is so wrong that I’ve just sort of given up.”

Yet there is enormous pressure being exerted on her over Yentl, and the irony is that the accomplishment of a dream has put her on the horns of a dilemma. She doesn’t want to be accused of over-promoting the film, of hyping Streisand. Yet she also realizes that a few public pronouncements can help her cause. She has scores of advisers around her, people who say do this and do that, but ultimately the decisions are hers, and she insists on making them herself.

“The theme of this movie is very important to me, the theme that nothing is impossible. I came to Hollywood, and people said I should have my nose done, I should change my name. Even my mother said I’d never be a famous actress because I wasn’t pretty enough. So I just thought to myself: I can do it.”

The smile, a mixture of irony and triumph, is a big one. She pulls down the cuff of her beige silk jacket, and stares into her tea for a minute before continuing.

“There is another reason this film is important to me. It’s very personal, and I don’t want to sound strange talking about it. It was away of resolving certain feelings about my father, a way of getting to know him.”

Her father died when she was an infant, before she could ever know him. He was a scholar and teacher, a man with Yentl’s love of learning.

“I had a lot of anger, and I always felt isolated. All my friends had fathers. Why didn’t I have a father? What did I do wrong? I never knew my father really existed. I never had a picture taken with him until 1979, when I went to visit his grave and someone took a picture of me standing by his tombstone.

“Then one day my brother, who is older and did know our father, talked me into going to a psychic. This sounds so odd, so crazy. I am a skeptic—I look for the wires under the table. I don’t believe easily, and yet I do believe. I guess you might say I believe in the soul transcending matter. The medium sat at the table and spelled out the letters ‘B-A-R-B’ and I said ‘Barbra.’ Then she spelled out my father’s name. I was so scared I got up and went to the bathroom. When I came back, the medium asked if there was any message for me. She then spelled out ‘SORRY’ and ‘SING’ and ‘PROUD.’

“After that I never wanted to go to a psychic again. It was enough for me somehow to believe my father was speaking to me, was telling me to make this movie. Who knows? It might have been my own energy wanting me to make this movie. I think if I’d made it any time before this, I would have been much more judgmental. I would have found a way of putting men down, somehow, or of expressing my anger that I didn’t get to have my own father. I needed to talk to my father and know that he didn’t die because I was a bad girl or anything like that. He died because he was sick, and he loved me and he was proud of me. It took me a long time to realize that. It was as though making this film was a way of working out my relationship to my father. To me he now exists. I always felt during my life that I had taken on his persona, that I was carrying on my father’s life by making something of myself. That’s why I dedicated the film to him and to all fathers.”

Then, to dispel the serious mood, she launches into a story about showing the film to her mother: “She loved it. She cried. Then she called me up and said she thought I should change the ending. I sat there thinking, she doesn’t like it? But that wasn’t it at all. ‘When you dedicate the film to your father, you should also dedicate the film to your mother!’ ” There is a whoop of laughter. “She was in there pitching right to the end. I said, ‘Ma, I’ll do another movie about mothers. I’ll dedicate that to you.’ ”

For years the saying around Hollywood has been “Give me Barbra Streisand and five songs, and I’ll get a movie deal.” Her clout was so great that this was all it took to get backing.

“I’ve heard it, too,” she says. “But everybody turned down Yentl. It’s got a terrific, universal story, and it’s got ten songs. You’d think because I’ve got a pretty successful track record they’d have agreed. I have produced or co- produced other movies that have been on budget. I don’t have a reputation for going over budget. They were afraid of my perfectionism, I know that. And studio executives don’t like the idea that actors also like to direct sometimes.

“I don’t think it had anything to do with my being a woman. But I do think it had to do with being a first-time director and wanting to go off to make a period film in eastern Europe. That would make anybody nervous.

“There’s another thing, . . .” She pauses, choosing her words carefully. “I think there are certain people in this business who get a pleasure out of saying, ‘Guess who I turned down today. I turned down Barbra Streisand.’

“At first I was saddened by it. I felt as if I were eighteen years old again, going out to tell people I could act. They’d say ‘Yeah, well, where can we see your work?’ I’d say, ‘I don’t work anywhere, but I would if anybody would give me the chance.’ The answer was always: ‘In order to consider you for this job we have to see your work.’ I spent several years running around saying, ‘Hey, wait a minute, which came first, the chicken or the egg?’ Which is why I turned to singing. It was a way in. Then when I wanted to do Yentl, it was the same thing all over again. I had to prove that I could do it. With enormous self- doubt, I might add. But I’m one of those people who, if you say no to them, simply don’t take no for an answer. No frightens some people off. It gives me a challenge.”

Now the project that began 16 years ago is finished, and the personal cost to Barbra Streisand has been high. One casualty was her nine-year relationship with her live-in companion, Jon Peters. Peters was one of the great champions of Yentl and was at one time one of the producers, too. His own commitments and her growing independence altered the situation, but even when she was shooting the film in Czechoslovakia, Peters would fly in from time to time to lend his support. He still gives his advice and support, but the rest of it has ended.

“We’re separated,” she says. “But I look at it another way: We lasted nine years. In this town that’s an accomplishment.”

As she recently told Geraldo Rivera for ABC’s “20/20” broadcast: “I had to go away. I had to leave him. . . . I had to go away to Europe and be my own person and help myself, because Jon actually protected me a lot, kept me insulated. . . I needed to protect myself; I needed to see if I was strong enough mentally, physically, emotionally to succeed in this project.”

And will they pick up the pieces again? “I dunno,” she told Rivera. “It’s for the fates—you know?”

Her son, Jason (by ex-husband Elliott Gould), is 17 and involved in filmmaking, sculpting and otherwise being a teenager. “It hasn’t been easy being my son,” Barbra says of him. “We cannot go out and do the things other mothers and children do together. We end up jumping into cars to avoid photographers. My privacy is easily invaded, and his is, too, when he’s with me. I don’t like my picture taken. I feel like the Africans—you know, who believe when somebody takes your picture they take a little bit of your soul. It makes me feel like an object, an image—things I think I am not.”

She is famous—some would say notorious—for having a gut instinct for what is right for her and for following that instinct religiously. On set she is questioning, exacting and sometimes exasperating. One wonders what it must have been like for Streisand the director to direct Streisand the star:

“It’s hard to answer properly. I had no time to cater to Barbra Streisand the actress. I had no time to make sure I was photographed from all the right angles. In fact, when Yentl becomes Anshel, I did something I never do in movies. I photographed only the right side of my face. My face has two distinct halves, and the left looks much better on film. It’s as though l saved the other side of my face all these years for this. I was also very aware of not being self-serving. Barbra-the-actress couldn’t get her close-ups first because Barbra-the-director was otherwise occupied. Also, the director was saving the really beautiful looks for her leading lady, and that was Amy Irving. I spent a lot of time making sure she was lighted right and that she looked absolutely gorgeous.”

Yentl cost $16.5 million to make, and it went only 11 percent over budget—a small overage for such an ambitious and massive undertaking. Streisand’s salary as director was scale—$80,000, half of which she put back into the film in order to rescore some of the music to her exacting standards. Her overage caused the company insuring the budget to step in, resulting in a flurry of stories that the picture had been taken away from her. Not so. The final cut is hers. The outcome is now up to the critics and the audiences. She expects some criticism—particularly about the ending (which she changed from that of the Singer story)—but she is proud of what she has done. And she is loath to let go of it.

“It’s one of those things you don’t ever want to end, yet you also cannot wait for it to end. You know what I mean?”

And now?

“I want to do nothing for a while. Then maybe I‘ll do a television concert, but not one people expect of me. I hate repeating myself, which is one of the reasons I don’t do concerts. The audience always wants me to sing the songs I’m known for. I don’t want to re-create my past. I want to go on to something new. I want to constantly grow, constantly change. That’s what I loved about making this film. The process is alive. Every step of the way it changes, it grows, it modifies, it expands. It’s fascinating.

“I’ve exercised my artistic muscles now, so now relationships are important to me once again. I want to develop my skills as a partner, maybe even as wife. I think partnering is an art. That’s what I’m going after now. That’s my next career.”

While many actresses worry about aging, Streisand, at 41, sails on unperturbed. If she’s worried, she hides it well. “After all,” she says, “I caught this thing called fame when I was eighteen, and so it seems that I have been young almost forever. I don’t mind aging. I sort of look forward to it. Besides, one of the nice things about having oily skin is that you don’t wrinkle much. Look close. Real close. See any wrinkles?”

You look, and you don’t.

End.

Related Page: Yentl

[ top of page ]