Ladies' Home Journal

December 1983

By Cliff Jahr

“I was scared to death making Yentl. I was frightened I wouldn’t survive it because my father died when he was only thirty-five years old, and my mother always told me that hard work kills you. So it’s like . . .”

She breaks off to release that familiar Funny Girl laugh tinged with shyness.

“Well, I realized this experience of producing, directing and starring in a movie could literally kill me. I knew I had to be strong. I couldn’t crumble, or everything else would crumble around me. I couldn’t get sick, couldn’t be too tired, couldn’t be too anything. And it was wonderful to feel myself getting stronger each day, even though fright still made me sick every morning.”

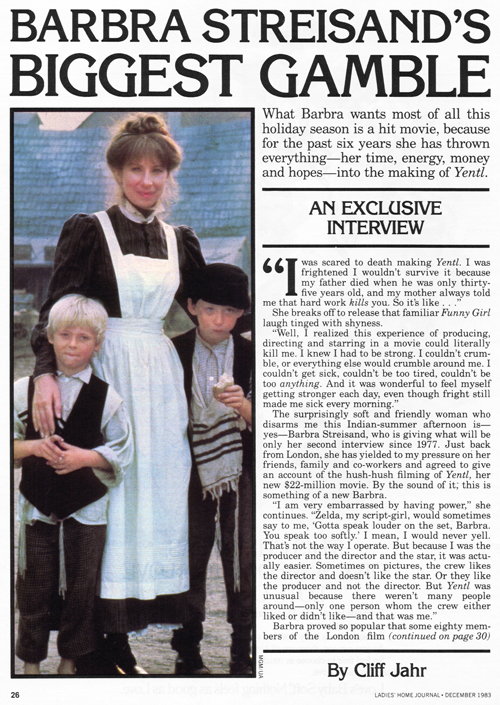

The surprisingly soft and friendly woman who disarms me this Indian-summer afternoon is — yes — Barbra Streisand, who is giving what will be only her second interview since 1977. Just back from London, she has yielded to my pressure on her friends, family and co-workers and agreed to give an account of the hush-hush filming of Yentl, her new $22-million movie. By the sound of it, this is something of a new Barbra.

“I am very embarrassed by having power,” she continues. “Zelda, my script-girl, would sometimes say to me, ‘Gotta speak louder on the set, Barbra. You speak too softly.’ I mean, I would never yell. That’s not the way I operate. But because I was the producer and the director and the star, it was actually easier. Sometimes on pictures, the crew likes the director and doesn’t like the star. Or they like the producer and not the director. But Yentl was unusual because there weren’t many people around—only one person whom the crew either liked or didn’t like—and that was me.”

Barbra proved so popular that some eighty members of the London film crew sent a letter to the editor of an English newspaper expressing their “collective affection” for her. “She has completely captivated all of us. . . .” the letter read, “. . . she appears to have no temperament.”

The letter brought tears to Barbra’s eyes. “I was so touched,” she sighs. “People have this image of me as being difficult, tough ... When I arrived on the set that first day, this man shook my hand with a sweaty palm. I said, ‘Are you nervous?’ and he said, ‘A little,’ and I said, ‘Well no one’s more nervous than me. We’re all in this together, and if you make a mistake, it’s fine, because I’ll be the one making most of the mistakes.”’

Not too many, let’s hope, because for sixteen years the forty-one-year-old star has been breaking down the resistance of Hollywood brass to make this movie. Finally, what used to be called “Barbra’s Folly” will open this month.

Yentl tells the story of a young Jewish woman in a turn-of-the-century Polish ghetto who masquerades as a man in order to become a rabbi. Then, to maintain the disguise, she is obliged to wed—and bed—an ex-fiancée of the man she loves. (Wags have dubbed it Tootsie on the Roof.) In the short story by Nobel Prize- winner Isaac Bashevis Singer, on which Yentl is based, the main character is a fourteen-year-old girl. Streisand, who looks young but not that young, raised the age to twenty-four.

If critics and audiences love the movie, it will surely certify Streisand as number one in the living-legend department. If they don’t, however, she may have to pay a price reminiscent of the bittersweet endings of her biggest films, Funny Girl, The Way We Were and A Star Is Born.

For now, however, Barbra’s life bubbles like a champagne comedy. Despite nearly a three-year absence from the public eye, she still tops the popularity polls, her latest records have sold better than ever, and her real estate, art collection and other holdings are estimated at well over $50 million.

There’s also new zip in her love life. She has dated a succession of handsome men, including actor Richard Gere and director George Lucas (Star Wars). She separated amicably last spring from hairdresser-turned-film- producer Jon Peters (Missing, Flashdance) after almost ten years. “Our relationship is closer than ever,” Peters explained. “We are the best of friends. We are still in business together in some respects. I love her dearly and I think she feels the same about me.”

Lately Barbra has been seeing Steven Spielberg, touching off speculation that the director of E.T. was quietly giving her a hand in the editing room. The very idea makes her bristle. “Do you know how repulsive that is to me?” she snaps. “I hate it. It’s like they’re already taking my film away from me! Steven and I were making separate movies on the same lot in London. I would come to his set every day. We’d see each other every once in a while. We talk about people and life and work. Steven’s a friend of mine . . .” She pauses for emphasis and repeats, “A friend of mine. Do you know that one tabloid had me breaking up his impending marriage. That’s ludicrous!

“George Lucas and Steven Spielberg always show each other their films. I’ve shown both of them Yentl, and I’ve also shown it to lots of other people. Spielberg showed his Raiders of the Lost Ark to [director] Martin Scorsese, so now you’re going to say Scorsese helped edit Raiders?

“They’re my peers, you know. I do or I don’t agree sometimes with what they say, but that’s the process of filmmaking. I hate tooting my own horn, but when Steven saw Yentl he said, ‘I wish I could tell you how to fix your picture, but I can’t. It’s terrific.” Someone also heard him say, “It’s the best first film since Citizen Kane.”

“The way I work,” Barbra continues, “I always want everyone around me to contribute. I’ve gotten in fights with directors before because maybe I’ve asked the sound man for his opinion, and the director will say, ‘What, are you crazy—asking a sound man?’ and I’ll say, ‘But he’s the audience, he’s also a human being, he has a mind.’ I like to use the opinions of everybody, not just the the so-called top people.”

But Barbra can’t altogether ignore the opinions of filmdom’s top people. And the first executive screenings of Yentl brought reactions that ranged from “masterpiece” to “slow.” “Yeah,” she agrees. “I’m sure that’s exactly what audience reactions will run to. It is long—two hours and fourteen minutes. If I could have taken out ten minutes, I would have. I can’t. If you find it slow, don’t recommend it to your friends. I don’t want to cut any more of it, so that’s that.”

Well, not quite. Contractually speaking, United Artists, the studio releasing Yentl, had the last word on its length and casting. Barbra ultimately had to concede this most coveted of powers, the final cut, as the only way to get $14 million of financing. The concession, however, may prove only a small bump in Yentl’s rocky road to the screen.

Barbra first optioned it in 1967 and ten years later planned only to direct. (“I’m too old to play it myself,” she explained.) But Hollywood investors saw the proposal as risky unless Barbra also starred and sang, and she finally agreed. During the last five years, while the script has gone through countless writers and rewrites (Barbra also coauthored), the project has been in and out of several studios, including Polygram Pictures while Jon Peters worked there. However, mixing love and business proved a strain on their relationship. They found themselves “butting heads,” according to Peters, and the film finally wound up at United Artists.

Then, in the summer of 1982, filming in Czechoslovakia took longer than planned, so that later scenes—shot on a boat near Liverpool, England—faced storm- tossed autumn seas. Costs climbed 10 percent over budget, and though Streisand put up $1 million of her own money to help cover it, she had to surrender the film’s checkbook to the bonding company that had insured Yentl’s completion. Her enemies laughed, but it was much ado about nothing: Barbra still retained artistic control up to the final cut.

She has dedicated Yentl to her father—as well as to “fathers every- where”—giving tribute to a man she never knew. In fact, it is widely said that Barbra is obsessed by the memory of her father, Emanuel Streisand, a likable, scholarly high school teacher. In June of 1943, he died of a stroke when Barbra was only fourteen months old. Her mother, left virtually penniless, cried in bed for months before finding work as a bookkeeper. She deposited young Barbra (then spelled Barbara) and son Sheldon, aged eight, into the care of their grandmother until she remarried six years later.

“Barbra is like her father in many ways,” says Barbra’s mother, Diana Kind, seventy-four, now twice-widowed and living quietly in a Hollywood apartment given to her by her daughter. “She, too, is always striving for knowledge.”

How would he have felt about Barbra’s success? “I hate to think,” says Mrs. Kind, breaking into that blushing laugh like her daughter’s in Funny Girl. “Of course he would idolize her, but he would have been as alarmed by her going into show business as I was.

“You know,” she continues, “my daughters singing comes from my side, I think, because I have a nice voice, and my father was a cantor. I had noble intentions of becoming a diva in the Metropolitan Opera, but that was only dreaming.

“Barbra has my blue eyes,” she adds slyly, “but she has her father’s nose. She got that nose—well, that’s what grew on her face, and it’s very pretty sometimes, really adorable.”

“My mother,” sighs Barbra good-naturedly. “I can’t keep her mouth shut. I keep saying, ‘Mom, stop talking about me.’ She doesn’t listen, but that’s okay.”

As Yentl’s opening day nears, tension builds as insiders wonder if the unusual story and ethnic setting will translate to ticket buyers as “arty,” much like Warren Beatty’s Reds, which was distinguished but a box-office flop. There’s also the movie version of Fiddler on the Roof another so-called “Jewish musical,” which barely broke even at the box office.

Despite these concerns, Streisand’s unstoppable drive to make her movie was fueled by a midlife rediscovery of her Jewish roots—or so everyone keeps saying. They point to her recent Jewish philanthropies, her study of Hebrew, and her attendance of a Bible study class.

“I was doing research for my film,” explains Barbra simply. “Studying the Talmud is a fascinating, enriching experience, and, of course, I came out of it being proud I was a Jew, but I don’t go to synagogue regularly. Calling me a born-again Jew is ridiculous.”

Ironically, despite all the religious homework and good intentions, Yentl might still offend some conservative Jews, who will see it as playing fast and loose with their heritage. An Orthodox rabbi, a onetime advisor on the picture, asked to have his credit removed. According to an insider, “He just begged Barbra to take out of the script a lot of things that he felt were unauthentic and obsessed with sex. There was one scene at a mikvah, a Jewish bathing ritual for women, that had rabbinical students peering at them through cracks in the wall.” (Barbra did cut the scene.)

Another scene (which remains) has Streisand, disguised as a man, kissing her naive bride on the honeymoon night, then doing some fast talking to delay consummation. Later on, she reveals to the man she loves her true gender by opening her shirt to expose a woman’s breasts, though only Streisand’s back is shown. Such cruel deception and wildness could never have happened, the rabbi insists.

“I’m sure Yentl won’t have the Jewish community’s complete approval,” Barbra notes matter-of-factly, then shrugs and smiles. “Jews like to complain, you know, like to have opinions. I’m sure they’ll disagree. But when the press says I’m disguising myself as a man in drag, that’s mean of them, because the movie’s not about whether I can look like a boy or how good the makeup is. What I was trying to do is explore the male and female within all of us, the androgeny of the mind and the soul. Calling it drag—that hurts. I’m anticipating press reaction so much that I’d almost like to just lock the film up and show it only to friends.

“I’ve been burned many, many times by the press, and I don’t want the film to be tarnished before it even comes out. I was deeply hurt by an article about A Star Is Born written by Frank Pierson [its director], from a purely subjective point of view. His article came out just before Star opened and a lot of the reviews even quoted it! [Note: Although A Star I s Born was slammed by critics, it made everyone a fortune]

“This American habit of destroying our heroes after we’ve built them up,” she says, beginning to seethe, “it sickens me. I don’t know why it’s done. Oh, I know it’s fascinating to learn what’s behind the personality, but why are we not trying to elevate the consciousness of people and the nature of life? Why is everybody trying to destroy everything, to put everything down?”

Surprisingly, Barbra doesn’t seem to realize she may be America’s biggest star, and that people are eager to cut through the myths that have grown like weeds around her.

“What myths?” she pleads in a reasonable tone. “I have not done a movie—a real movie—in several years. I worked in All Night Long for a few weeks because I was so tired of writing Yentl that I had to get off my rear and get away from the table and act.

“What matters to me is the work, and I don’t know why people have to know all about me personally in order to like my work—work that I care about passionately. I don’t sit home and think, ‘Gee, I’m a big star.’ As a matter of fact, stardom makes me very uncomfortable. For example, I’ve just had a meeting in which I took some mentions of my name off the ads. Why? Because being a woman, I’m going to get flak for doing all those things — producing, directing and so on — whereas when a man does all those things, they just find him ‘accomplished.’ Look at Lucas or Spielberg. They run their names four times; I think it’s embarrassing. What bothers me is that when a woman does something like this she becomes threatening.”

With so much at stake, what would she do if Yentl failed? Would she come back fast with a screwball comedy‘?

“Oh no, I would never do that again. I wasted a lot of time making pictures for the wrong reasons. I could never make The Main Event again. I made Yentl because it has meaning for me and because I wanted to be responsible for myself and my work. And from now on, I want to make films about relationships and personal growth, movies where audiences come out inspired to change. Whether or not people like Yentl, it is a movie to be reckoned with. I didn’t realize that until I saw it in London. It was such a personal vision that I’d begun to lose objectivity, and I started to think, ‘Oh, God, maybe I made this awful thing.’

“Then a few distinguished people started reassuring me and I was dumbfounded. Part of me, in fact, didn’t even like all this good word-of-mouth from them. I thought, ‘Oh, my God, this makes me think of Woody Allen’s Zelig.’ You know how brilliant Zelig is . . . brilliant the first half-hour, then you start looking at your watch . . . it’s a picture you admire from afar and can’t get involved with. Yentl is just the opposite, and may even be criticized for being emotional. George Lucas said it made him cry, and he never cries at films.”

Barbra gazes off reflectively. Maybe one can still see in her face the little girl from Brooklyn. “Oh, sure, I made mistakes,” she sighs, “but after sixteen years I did pull it off, and I did the best I could. This picture has changed my life. It has been my ultimate growing-up test.”

End.

[ top of page ]