Streisand in “Star is Born”: The Way It Is

L.A. Times

May 2, 1976

BY LEE GRANT

PHOENIX—A Star is Reborn.

Here, in a city the locals call “Valley of the Sun,” more than 100 reporters from newspapers, radio and television stations throughout the country were gathered together by Warner Bros. in a massive public relations ploy to push the remake, again, of “A Star is Born.”

The troubled project would seem to need all the help it could get.

The idea for a new film with a new angle and a “love story” script was conceived more than three years ago by writers John Gregory Dunne and Joan Didion. It has since been through a myriad of Hollywood typewriters — how many is unclear.

The Dunne-Didion notion was to take the old Fredric March-Janet Gaynor, and later James Mason-Judy Garland love story of two movie stars—one on the way up, the other on the way down—and update it into a similar story of two rock stars.

Offered to Peter Bogdanovich and Cybill Shepherd as a film called “Rainbow Road,” then, in no particular order, to Liza Minnelli and Elvis Presley, Carly Simon and James Taylor, Diana Ross and Alan Price, it finally filtered over to superstar hairdresser Jon Peters, the self-defined "street-fighter" and Barbra Streisand guru.

What came next is a complex mishmash of personality and title. John Foreman was producer; Mark Rydell had been director, though leaving before Peters entered with Streisand. She had decided to star with country songwriter and Pomona College Rhodes Scholar cum actor Kris Kristofferson.

Warner Bros. wanted Streisand (whose previous film, “For Pete's Sake,” earned $10 million) and Streisand wanted Peters. She wanted him, at various times, to direct, costar, rewrite the screenplay and produce.

Dunne and Didion stepped aside amidst the turmoil, settling for their fee and a percentage of the picture. Jerry Schatzberg (“Scarecrow”) came aboard to rewrite the screenplay and direct.

Peters asserted himself; Foreman left. The script was taken from Schatzberg's hands and moved to a young friend of Peters; Schatzberg left.

“God knows how many writers have been on it since us,” Dunne said, relieved, seemingly to be away from it all. “I hope it makes a bundle of money because we have part of it. I wish everyone well.”

The film began to take shape when Peters scored an unexpected coup, landing Frank Pierson, a gritty Academy Award-winning screenwriter (“Dog Day Afternoon”), to take over the script. His orders from Peters: “Make it tougher.”

Pierson not only made it tougher but stayed on as director. Although accumulating a number of directing credits in television, “The Neon Ceiling” among them, this was Pierson's first motion picture assignment.

He has brought a settling to the affair, a professionalism and tact which offsets Peters, the novice who has assumed the role of producer.

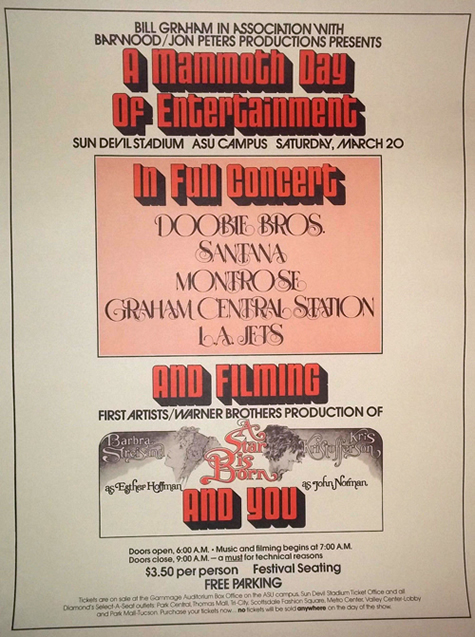

Into the center of this, Warner Bros. shelled out thousands of promotional dollars to bring the press together for three days of pack journalism at a rock concert staged for the film at Arizona State University in suburban Tempe.

They were a peculiar mix, these reporters — hard-nosed gadflies and star-struck youngsters, fan magazine puff writers and intellectual Eastern critics, all drawn together by an actress who said, “I never read newspapers.”

Headquarters was the new posh-plastic Hyatt Regency Hotel in downtown Phoenix. Each reporter's room contained a canvas-type tote bag, “A Star Is Born” logo in black on its front flap. Inside was “A Star Is Born” T-shirt, “A Star Is Born” beer mug, a copy of Streisand's latest album, Kristofferson's latest album and, buried at the bottom, a press kit.

On a table nearby was a printed information packet including a schedule for three days—where to go, at what time; where to eat, at what time; whom to interview, at what time.

The concert was set for Saturday but Friday was when Streisand, Kristofferson and others connected with the film would meet the press. They were to meet them in a unique though not very professional setting—a luncheon catered on the 50-yard line of the football stadium. There would be a few minutes at each table to ask questions, not much chance for anything but the barest trivia. Puff is what they were dispensing but puff is not what some of the reporters were taking. There would be words between them and the press agents, the publicists, the public relations people.

“Sorry,” said one writer. “We will not ask Ms. Streisand her favorite color.”

On a chartered bus to the stadium, the reporters were restless, surly, talkative.

“It's 2 to 1 Streisand doesn't show,” said a writer for a European daily.

The talk was of bylines, famous stars interviewed, name-dropping, a weakness for movie stars.

One reporter asked aloud: “Got any dope?” A dark cigarette changed hands.

The temperature was in the high 80s and a Chicago radio reporter, inexplicably in three-piece dark suit, got sick to his stomach.

At the stadium, the number of professional publicity and public relations persons nearly matched, it seemed, the number of reporters. Warner Bros. had gathered its news-manfuacturing forces from Hollywood, Chicago, Toronto and Atlanta.

Their greetings, at different times from different persons, as if coming from a machine, were identical:

“Hello. Nice to see you. Thanks for coming.”

“Hello. Nice to see you. Thanks for coming.”

“Hello. Nice to see you. Thanks for coming.”

Also along were press agents representing the stars. They regarded their clients, for the most part, as sacred and omnipotent, guiding questions, manipulating where they could, shutting off the source where they couldn't.

Photographers were warned not to take candid pictures of Streisand while she sat at the tables, but to wait for arranged setups. “Don't tell us what to do,” barked a grizzled photographer from a news magazine.

The journalistic line of the day came from Arthur Bell, the chatty Village Voice columnist. “I guess I'll write an ambience piece,” he said, straight-faced.

The reporters were milling furiously, on guard for tidbits, information they could gather that 99 others couldn't. They eavesdropped on conversations, planted rumors, used the weight of their respective newspapers or stations to garner favors.

The prize was a personal interview with Streisand. None would be forthcoming. Her press agent: “No one-on-ones. She's tough. You know how tough she is.”

The reporters were agitated with the public relations types who'd refined their art of feeding news to the press at their own rate, just the right amount at just the right time.

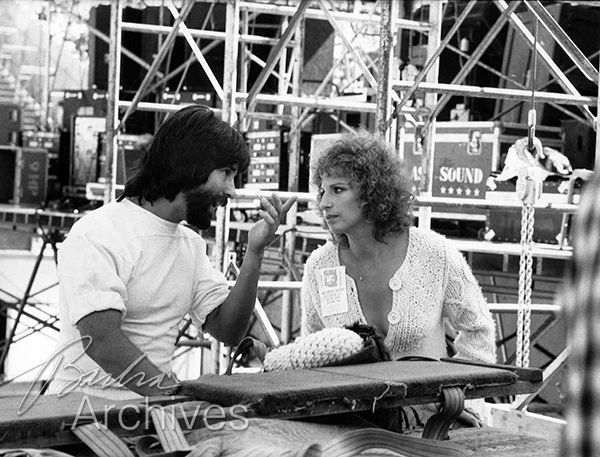

Finally, when tensions peaked, Streisand, Kristofferson and Peters strolled from behind the stage to greet the press. She, naturally, took center stage, wearing, and nearly falling out of, a long white cardigan sweater, open to the navel. A small, gold Star of David clung at her neck.

Streisand agreed to first pose for pictures. The photographers ran up to her, after her, nearly knocking her down, pushing each other out of the way for a better shot, a different angle. A heated exchange occurred, punches thrown.

“It's like a film within a film,” observed a reporter from San Francisco.

It all seemed silly to the laid-back Kristofferson. He looked into the cameras and ordered, “Vote for Jerry Brown.”

Streisand was guided to the tables by an exceptionally attractive Warner Bros. publicity woman with a thick English accent. The star looked at her and then delivered a stinging and pointed lesson in front of the reporters on how to pronounce the word “Streisand.”

Streisand was guided to the tables by an exceptionally attractive Warner Bros. publicity woman with a thick English accent. The star looked at her and then delivered a stinging and pointed lesson in front of the reporters on how to pronounce the word “Streisand.”

The questions, meanwhile, were hurried, routine, often banal—how she likes the film, who cuts her hair, when is she getting married, ad infinitum.

Standing guard behind her, ever-present, protecting the account, was the press agent, screening questions as best he could. “I've got a job to do,” he said.

A handful of reporters, following their news instincts, didn't wait for the planned visitation to their tables, but pursued her, following, slipping in questions when they could.

Sniffed a Warner Bros. publicist: “How rude.”

Streisand said the film was important to her because the role depicted a woman “not afraid to confront the male society. We're taking a lot of chances, dealing with lots of issues about role playing, what is female and what is male.

“Women in films and in general have been treated as objects. I respect the new consciousness. In this film, the woman helps the man all she can but doesn't give up her career doing it.

"In this one, he cries.”

A ga-ga reporter from a large Chicago paper interjected: “Oh, Ms. Streisand, you were so wonderful in 'The Way We Were.'”

Responded Ms. Streisand: “Feh, I was not.”

Others began asking her for autographs, boldly suggesting they were “for my kid.” Streisand pressed on.

She views the new “A Star Is Born” “as a love story, our love story, Jon and mine's love story, a consideration of the kinds of things we're working at in our relationship. It's a combination of the tough attitude of Frank Pierson, the softer one of the Dunnes and my own shmaltz.”

The picture will carry this designation: A First Artists Presentation, a Barwood/Jon Peters Production for Warner Bros. release. That means Streisand's money is involved, one reason she is talking to the press at all. She has also taken the title of executive producer.

“As executive producer,” she said, “I had to become an adult in this film. The choices are mine and Jon's. It all means I'm in control. It's an extraordinary responsibility. I never had power before.”

The importance of power and control emerge in a hypersensitive reaction to her treatment in “The Way We Were.”

“I came off simple,” she said. “lt hurts to have key scenes of my films cut out. In this one, there will be no scenes I don't want; all the scenes I do want.”

The film will include music by a number of rock 'n' roll heavyweights including Leon Russell, an ingredient which has become a challenge to her.

Sliding from a pop-Broadway orientation, Streisand has written two of the songs herself with the help of Russell and the influence of Bruce Springsteen.

“I love rock music,” she said.

There is a bristle at the criticism the movie has already received. “There are lots of projects where the script is rewritten seven times,” Streisand said, “or the star's husband hits the director. You don't hear about those but I'm more controversial.

“People think of me in narrow terms. They said I couldn't act because I was a singer. Because my boyfriend's a hairdresser, why can't he be a producer?”

She pooh-poohed the stories in national news magazines suggesting a strain between her and Kristofferson.

“He's very honest,” she said. “You can't fake it with him. He's frightened a lot of the time but it works for the role. There is a gentle craziness to him.”

All the while, Kristofferson sat almost alone at another table. Streisand moved over to join him for a last round of questions. She placed her arms around his chest, grabbed his face and told the gathered, “I'm learning from him and he from me.”

Said she: “He's great.”

Said he: “She's great.”

Said she: “I told you he was beautiful and honest.”

And then this press conference was over, Peters taking Streisand by the hand and walking with her back to their dressing room.

The horde of photographers scurried after them, cocking their cameras, knocking over a table of food, clicking incessantly. Streisand and Peters shook their heads at the tumult. It was a scene from a bad movie.

“Gruesome,” said a bystander.

____________

“Why are you so rude?” a fan magazine reporter bluntly asked Jon Peters.

“That's the way I am,” he bluntly answered.

Peters concedes he is rude, short, surly to the people who need things from him; charming and pleasant, when he needs things from them.

He's a chunky man, half-Italian, half-Cherokee Indian who grew to manhood in Los Angeles hovering on the precipice of juvenile delinquency.

At 15, he married and ducked to Europe. A short while later came back, unmarried, and enrolled in beauty school. Soon he took over the reins of his family's beauty shop business, expanding it to Beverly Hills and Encino where he catered to the follicles and follies of frustrated matrons.

Three years ago, he was called to Streisand's home to prepare the wig she wore in “For Pete's Sake.” He was kept waiting hours and when finally she showed, Peters snapped, “Don't ever do that to me again.”

Something snapped in Streisand. She liked that, a change from the usual ego-pacifiers surrounding her.

“There have been lots of lies written about us,” said Peters, relaxing in brown suede pants and vest on the manicured grass of the football stadium. “It's all part of the game. We've gotten attacked on this film because we have guts enough to do something we wanted to do.

“Because we're taking chances, others get uptight.”

At 31, his personality may have turned people off along the way but there are standards from which he won't budge: “I am treated as I demand to be treated.”

Peters explained the early problems on the film, the heavy turnover, as “just the way it is. Lots of movies get rewritten. Some people just didn't work out. They were all very talented but didn't contribute at the places our minds were in.

“It was our film and we wanted it our way.”

The movie will reflect “me and Barbra and how we feel about things, our relationship, the issues important in our lives. It deals with loving and will have language of a contemporary nature.

“A lot of it is about how audiences chew you up and spit you out again. The film will say love is not enough, you have to work and deal with your own life. We're working and dealing with our lives.”

The Kristofferson character, Peters said, “is a man I identify with greatly. It touches on the facts of my life — the street fighter and overachiever. The macho thing is very much me. I fought for what I believe in and was not above using violence.

“Now, though, I have found different ways to communicate emotionally. Since being with Barbra, I have gotten it together and feel right about myself as a human being. She has shown me that things can be different. I've evolved as a person. My desires and passions are the same but I don't feel as threatened.”

“You know, James Dean lived my kind of frantic life.”

Peters has assumed the role of producer with a certain savvy and style. He's in charge and likes it.

Remarkably, he will also bring the film in well under its $6 million budget. Having sold off his beauty business, Jon Peters is “out of hair and into films.

“It's my life.”

______

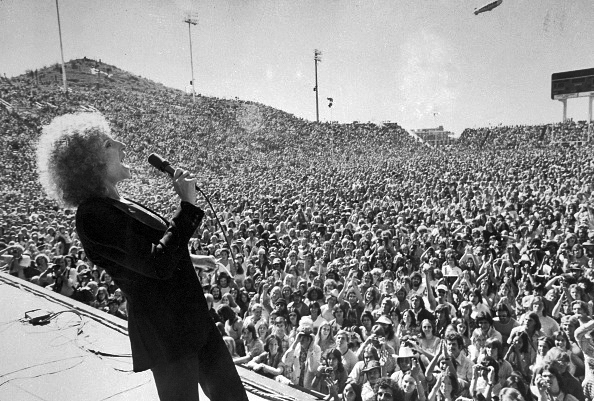

At 5 a.m. the stadium gates opened. It was important to have a large crowd early so filming could get underway at sunrise. The idea was to lure, with lowered admission prices and top-name rock bands, a stadium full of young people. The scheduled music would be interspersed with scenes being filmed of Kristofferson singing. A regiment of cameramen were in the stands taking documentarylike footage of fresh faces responding to the music.

Reporters were to be shuttled from the sky-high press box to backstage. They were allowed 45 minutes by the public relations people. Most, however, sloughed that off and remained backstage the full day near the action.

Bill Graham, the San Francisco rock impresario, as famous as the bands he presents, was brought in to arrange the concert. He corralled such name attractions as Peter Frampton and Santana and the result was a full-house crowd of nearly 50,000.

It was an important assignment for Graham who yearns to become further involved with films. He can be a kind and gentle man, according to those who know him, or brutal and crushing. This day he was curt and grumpy, impolite and profane.

At one point, the canned music between acts didn’t come on at just the right time. The succeeding tongue-lashing to an assistant carried throughout the area, rattling the yellow daisy Graham wore in his hat.

Amidst all this, director Frank Pierson, 49, worked steadily assisted by the venerable cinematographer Robert Surtees. Pierson, with stringy white hair and matching beard, seemed relaxed in blue jeans, cowboy hat and tennis shoes. His importance to this film has been underplayed. A recent national magazine cover story on the film neglected even to mention his name.

Author of screenplays for “Cool Hand Luke” and “Cat Ballou,” he is a listener and approachable. Sensitive with the young actors in the film's minor roles, Pierson takes time with them, encourages their moments, instills pride in their work.

Now he rests in an leather directors chair with his name on it.

“Streisand,” he said, “she's an incredible talent, affecting and seductive. Her tempo is fast, Kristofferson's slow. Together they're just right.”

On Peters: “He's inexperienced but learning fast. He has an enormous amount of energy. He's leaving the film-making to me.”

The crowd had become irritable, impatient, wanting more music, more concert; less filming, less take after take of Kristofferson's song.

Finally, Streisand ventured out to quiet them, tossing a few profane words out tastelessly in an attempt at identification, at “getting down.” One way to quiet them, she decided, was to sing. It worked, miraculously.

The songs were recognizable—“The Way We Were” and “People.” The throng settled, action on stage halted, the crew, Pierson, Peters, Graham listened. The voice took over. That voice, that Streisand voice, sailed over the stadium, igniting shivers. It caressed this boogie-oriented, raucous, rock 'n' roll audience. At the end, they delivered her a standing ovation.

Cradling it, smiling, at home here on stage, she told them, “Thank you. You're my first live audience in a long time.” It was Central Park come to Arizona.

_________

“Busted flat in Baton Rouge/ Waitin' for a train/ Feelin' about as faded as my jeans.”

— a song by Kris Kristofferson

Someone once observed of Kristofferson that “he's a fast-livin', hard-lovin’ dude who has just enough time between ballin' and brawlin' to jot down a tune or two.”

The tunes Kristofferson jotted down are some of the most respected, most recorded in pop music — “Help Me Make It Through the Night,” “Sunday Mornin' Comin’ Down,”“Me and Bobby McGee.”

At 38, he has the demeanor of one who has been around. A brilliant scholar who chucked it all, Kristofferson spent years as a janitor,working the odd jobs circuit around Nashville before his songs were noticed.

Of his songwriting, he said: “I see stories all over the place.”

Of his voice: “I sing like as goddamn frog.”

He is courteous and quotable, humorous and unpredictable, an intellectual, road-weary troubadour.

He has sprung forth in seven motion pictures (including “Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore” and “Blume in Love”) as a star with a cozy, vulnerable appeal.

Earlier, there had been a tense confrontation with a reporter from Rolling Stone magazine covering the concert. The magazine said this about his latest album:

“His decline as a songwriter is shocking ... he's just falling flat on his face ... the debacle of this album ... crap on vinyl.”

Kristofferson found the reporter and—although he wasn't the one who wrote the review—grabbed him by the shirt, screaming: “Next time listen to the whole album, not just one song.”

Working with Streisand, said Kristofferson, has not been easy. “I get really disappointed in myself,” he said, “not being able to adjust to the pressure, falling apart.”

There have, however, been consolations.

“I look around here,” he said, “and find I know more about music than anyone.”

Kristofferson said changes in the script have brought elements into the film which differ from his approach. “lt'll make you cry at the end,” he said. “It ain't the way I'd a done it.”

Kristofferson finds the project “scary, a tremendous responsibility. In this film, you see, I'm standing up for Janis (Joplin), Jimi (Hendrix), for every self-destructive artist. If I blow it, I have to answer to that.”

Kristofferson had achieved substantial success in literature, sports and the military before taking to the road.

“I don't regret doing what I had to do,” he said. “If I hadn’t, I'd been a dead man.”

Married now to the fine rock singer Rita Coolidge, Kristofferson said he works with an attitude of “just trying to get through to tomorrow, hoping for now that I don't wipe out two careers at once. Sometimes I feel guilty about being here. I need to use 99% of my talent all the time just to make it. Streisand can get by on 50%.”

For the moment, Kris Kristofferson is content “simply not working for a living.”

End.

Related: