West Magazine

September 1, 1968

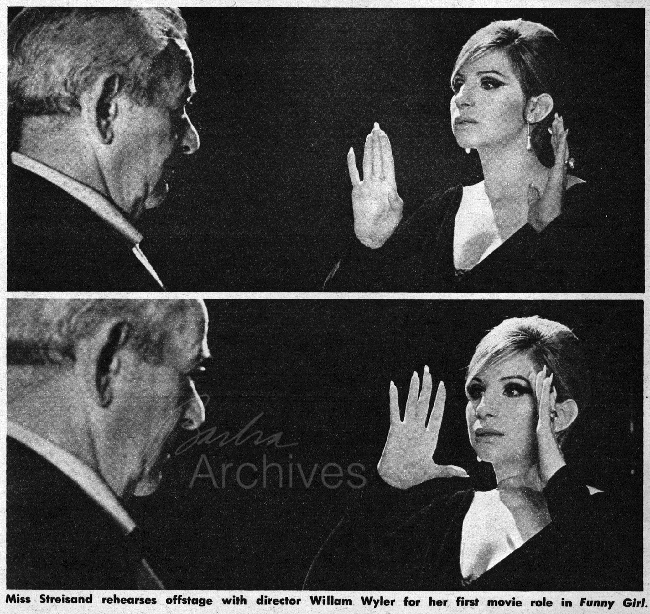

For her first three pictures Funny Girl, Hello, Dolly! and On a Clear Day You Can See Forever Barbra Streisand is making a million dollars each. Not a single foot of film has been released. No one in the history of the movies has ever done that before.

By John Hallowell

[NOTE: The same interview appeared in the Sept. 9, 1968 issue of New York Magazine. Hallowell has written a different introduction for West Magazine, and there are a handful of different questions/answers here, too.]

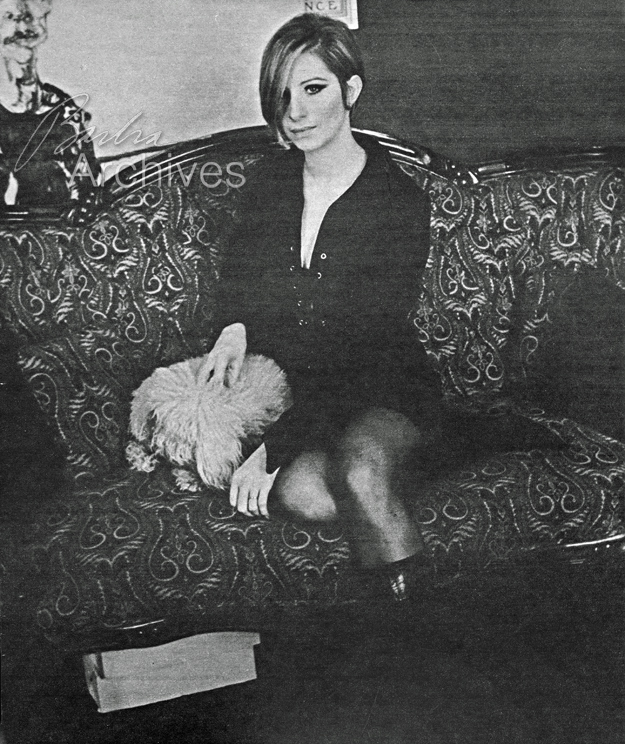

I have known Barbra Streisand for more than a year, and I've written about her three times. That was selfish on my part: except for Melina Mercouri, she is the greatest quote I've ever heard, a writer's dream. you can't make up lines that good—or true. As real as the concrete on Flatbush Avenue; as real as the way she sings.

Barbra is unto herself. When you are with her if you ever slightly tend to run on or try in a false way as we all do at parties to become instant soul mates, she crinkles her forehead like a little girl and goes back inside. She will never make easy relationships, any more than she will make easy songs.

That is why this story is so short. We worked very hard—now I know how the recording boys must feel at her fabled all-night recording sessions—through midnight calls and gutsy conferences, back and forth, paring, paring down to Barbra as she is. It would have been easy, and phony in her eyes, to do it otherwise. Every single word had to be true.

Streisand is the most honest person I've ever interviewed. In a world too often fake and glib, she is the Hemingway of subjects.

Hallowell: Let's start with something different. There's this game called "The Truth Game" and I'd like to play it.

Streisand: Okay.

Hallowell: If you were a car, what car would you be?

Streisand: Well, at times I'm an Excalibur. At times a 1925 Rolls ... and at times I'm a broken down Ford.

Hallowell: What about — what animal?

Streisand: My husband says I'm a hamster.

Hallowell: If you were a color, what color would you be?

Streisand: I think ... wine.

Hallowell: What bird?

Streisand: (laughs) Tweety bird. No, I'm some exotic jungle bird. And maybe an ordinary — not a pigeon — a little sparrow.

Hallowell: What century?

Streisand: I think the 19th, and the 15th, or is it the 14th? — Oh yeah! B.C.

Hallowell: What composer?

Streisand: Bartok ... a little strange and dissonant.

Hallowell: What article of clothing?

Streisand: A crepe black satin slip.

Hallowell: What painting by a famous painter?

Streisand: This is a good game. I like it. It's great for an interview, because it's sensuous and the only things that are important are the five senses. What painting by a famous painter? A Woman Bathing by Rembrandt.

Hallowell: What city in the world?

Streisand: Well, I've hardly been anywhere, so it's hard for me to say.

Hallowell: What famous historical character?

Streisand: Hmmm. I don't really identify with anybody.

Hallowell: What drink?

Streisand: Tab.

Hallowell: What period furniture?

Streisand: Louis XV, XVI, Victorian, and at the moment, especially Art Nouveau.

Hallowell: What flower?

Streisand: Gardenia.

Hallowell: What fish?

Streisand: A smoked one.

Hallowell: What astrological sign?

Streisand: A Taurean, who likes Virgos, Pisces and Aries ... Actually, I'm a mixture of heliotrope, burnt orange, fuchsia and gray — with a little dab of taupe on the side.

Hallowell: What other singers?

Streisand: Ray Charles and Florence Foster Jenkins.

Hallowell: What thing that can be bought at a soda fountain?

Streisand: Seltzer.

Hallowell: Now, let's talk about the press.

Streisand: Gee, from seltzer to the press.

Hallowell: How do you feel about some of the terrible press?

Streisand: Terrible!

Hallowell: Do you think your personality has been captured by the press?

Streisand: Captured ??? (She laughs) Slaughtered, barbecued, pickled!

Hallowell: How do you think the public interprets what has been written about you?

Streisand: Well, I think most people believe what they read, because of the power of the printed word. I only wish they would stop and think — hey, what about the personality of the person doing the interview? Maybe he didn't have enough sleep last night — maybe he has indigestion— maybe the laundry put too much starch in his collar. You know, we subjects have a lot to put up with! I wonder if the readers realize that each personality is being seen through the writer's eyes, neuroses, sensitivities, intelligence and perception — or lack of each one of these things.

Hallowell: Your critics say —

Streisand: What critics?

Hallowell: Some of the gossip columnists —

Streisand: Oh, the yentas.

Hallowell: (laughs) Forget that question. Compared to you now at 26, what were you like when you were eight?

Streisand: Smaller.

Hallowell: No, I mean what kind of kid were you in school?

Streisand: I got A's in all my subjects and D in conduct. See, I haven't changed at all! (She laughs) I remember at Yeshiva, they used to tell us that we couldn't say the word 'Christmas.' So as soon as the teacher went out of the room I'd say 'Christmas, Christmas, Christmas,' and be frightened to death that something would happen to me.

Hallowell: When you were a little girl, did you play with dolls?

Streisand: Didn't I ever tell you about my doll? God, I never had a doll, so I used a hot water bottle. I had this hot water bottle ... filled with water ... and I swear it felt real ... you know it was like a rubber tummy. And I had this pink sweater on it, 'cause the lady that took care of me was a knitting lady ... so I had this sweater on it ... and I had a hat covering the screw part of the top. That was my doll.

Hallowell: Were there any special movies that you liked as a kid?

Streisand: It didn't matter what the movie was — as long as it was in Technicolor.

Hallowell: Now that you're in your second "Technicolor" film — and a movie star — has your dream come true?

Streisand: Well, you see, I never really wanted to be a movie star in terms of signing autographs and being recognized and all that. I really wanted to be the character in the movie. I wanted to be ... not myself. I wanted to be Scarlett O'Hara ... not Vivien Leigh.

Hallowell: If you were a reporter, what question would you most want to ask Barbra Streisand?

Streisand: By the way, you say my name wrong. It's Strei-sand. Sand. Like sand on the beach.

Hallowell: How is it ... Streisen?

Streisand: Streisand.

Hallowell: Oh, Streisand.

Streisand: Yeah, but it's Strei-sand. On the first syllable. Barbra Streisand. How can I be famous — nobody pronounces my name right ... you never heard anybody say Bette DaVis.

Hallowell: Okay, another one. Do you ever worry about losing your voice?

Streisand: Of course not ... I think worry makes you lose your voice! No kidding, I don't believe in indulging my vocal chords. Mostly what makes me sing is my inner self and my acting. And if I want to hold a note because I think it's right at the moment, I hold the note, and if I don't want to, I really can't. I never sing in the shower ... I never sing by myself ... my voice comes out awful. When I had a sore throat as a kid, my mother used to put a woolen sock around my neck (preferably used!). I still do that ... with a safety pin. One day the safety pin is gonna open in bed ... Ahhhhgh! Puncture my vocal chords! That I worry about!

Hallowell: You love to eat, yet you have to discipline yourself as an artist. How do you handle the struggle between the two?

Streisand: How do I handle it? I'm eight pounds overweight, that's how I handle it! I keep on justifying it by saying I want Dolly to be a little Victorian. You know, a plump, Victorian figure? Sort of adds to my character. I'm a complete hypocrite about food. What I do is have chocolate souffle for dessert, and put Sucaryl in my tea!

Hallowell: Have you ever encountered prejudice?

Streisand: I don't know. I never applied to a country club.

Hallowell: Do you always love to laugh?

Streisand: Well, I think a lot of things are funny.

Hallowell: What would you do if the bottom dropped out of the Barbra Streisand market tomorrow?

Streisand: Look. Everything is momentary. You do a good picture, great; you do a lousy one, nobody wants you. That's why you have to have a husband, children, and antique furniture.

Hallowell: What is it like way down there, inside Barbra, where the singing comes from?

Streisand: Well, as somebody once said to me — 'There's a whole area inside you that has never been touched.' I guess it keeps people interested because I have secrets ... and I won't tell.

Hallowell: Finally, Barbra, are you happy?

Streisand: Are you kidding? I'd be miserable if I was happy!

End.

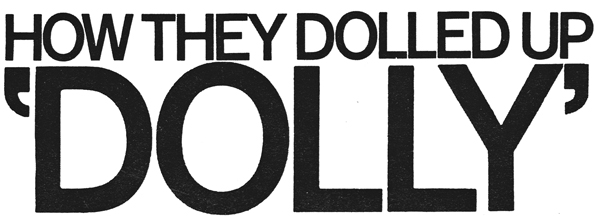

Sketching an idea is one thing; getting it onto film is quite another. Hello, Dolly! will go down in the books of this era of runaway productions as one very escpensive picture that put more people to work than any other in Hollywood’s improbable history. One of the first to get on the payroll was production designer John DeCuir, into whose epic-oriented imagination (Cleopatra, The King and I, The Agony and the Ecstasy among others) fell the task of recreating 1890 New York. His two biggest challenges: Harmonia Gardens, a fin de siècle saloon gorped up to the hilt for the film’s title song, and a nearby half-mile chunk of Fifth Avenue for a gigantic parade. After months of research, DeCuir presented his rendering (below). The outdoor parade set had a built-in problem: DeCuir had to wrap his $1.7 million fantasy around Fox’s sprawling stages and offices. The Century Plaza Hotel stuck up smack in the middle of Manhattan on the finished set (center, above), but well out of camera range. It took six months to build, three days to film, and the parade lasts just seven minutes.

Dolly Gallagher Levi, the irrepressible matchmaker played by Barbra Streisand, whirls like a dervish into one of Hello, Dolly! ’s biggest songs, Before the Parade Passes By. The parade she is worried might pass her by is a little $300,000-for-three-days concoction by Dolly's producer, Ernest Lehman: 675 people and 106 animals marching through a hired crowd of 3,108 extras on a set that cost $1.7 million.

“It’s all rather staggering when you think about it,” says Lehman, “so I just don't think about it.”

Never one to leave things to chance, Lehman even hired a meteorologist to tell him which three summer days would be best for filming. For once a meteorologist predicted well: the weather was neither too hot nor too cool. The light was perfect for the largest logistical undertaking in the history of Hollywood.

Before the shooting began, there was a day-long rehearsal with marchers only. Fifteen high-wheeler bicycle riders did their stuff while seven behorned women wrestled with their Tannhäuser costumes. Five midgets worked a maypole, while 40 Prohibitionists fought it out for equal time with 12 Suffragettes. Forty bagpipers somehow managed to squeal louder than pigs. All were drowned out by the 160-piece UCLA marching band in period costumes. Into this incredible array thundered 40 mounted Negroes pretending to be the 10th Cavalry Troop and 75 female gymnasts in bloomers stumbling over their wooden dumbbells.

The next day the marchers were joined by the 3,108 extras who were divided into nine big groups and told where they would be standing for the next three days. Then they trooped off for makeup and costumes. Two sound stages and three large tents, staffed with 122 specialists, got the job done half-an-hour before their 10 a.m. deadline.

Fifteen special assistant directors, most of them costumed and equipped with radios, joined 35 uniformed policemen and five costumed detectives in the crowd and everyone was shouted into place. Seven Todd-AO 70 mm. cameras began rolling 20 minutes ahead of schedule. Director Gene Kelly, operating with one the cameras on a boom reaching 80 feet into the air, masterminded the whole melee. He patiently reminded everyone to take off watches and sunglasses, and the parade took off and the crowd started waving their flags—most of them showing 50 stars instead of the more appropriate number of 44. And after all, it was supposed to be 1890.

But somehow it all worked and on the last day Kelly, slightly hoarse but indefatigably cheerful, wrapped it all up one hour ahead of schedule.

The last time anyone could remember seeing so many people at work on one picture was in 1938, when 3,000 extras turned out for Cavalcade. They came to film a funeral sequence. Thirty-five years later, some of the same extras turned out for a parade and another bit of Hollywood history in the making.

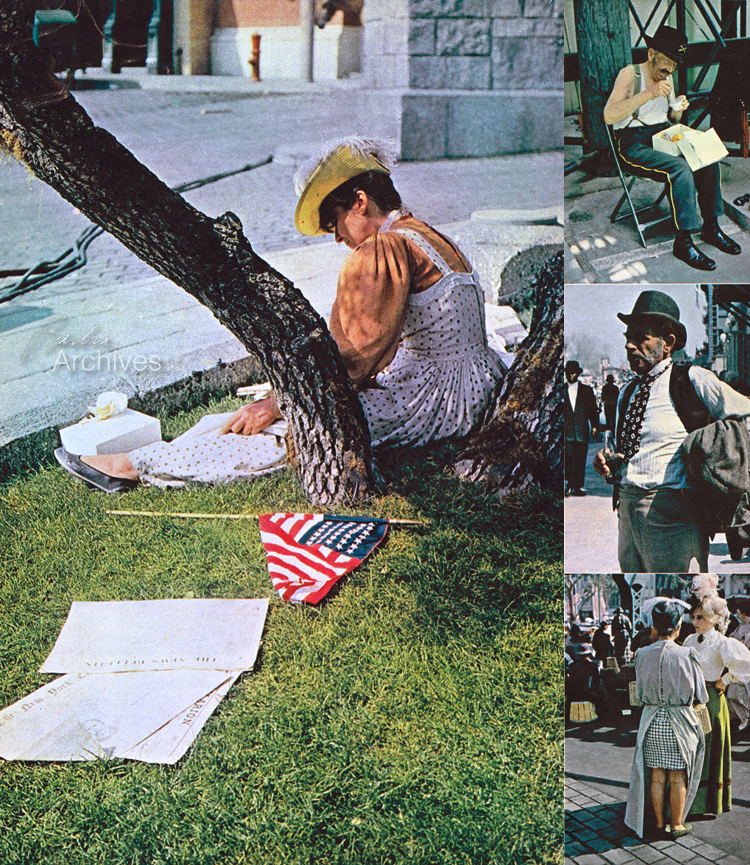

In military parlance, lunch is a support operation. But for film producers, lunch is one of those union-required interruptions which, if missed, can cost as much as a small war in a film the size of Dolly.

For three days, caterers brought in 4,200 box lunches per day and five catering trucks stood by with snacks. The army of extras, meanwhile (above and top right), ate heartily. There is plenty of time to kill between shots, either alone (right center) or gabbing with a friend (right) while revealing that under every 1890 woman's long, prim dress is a miniskirt just waiting.

End.

[ top of page ]