Life Magazine

February 14, 1969

by John Gregory Dunne

* Note: The late John Gregory Dunne was the screenwriter of Streisand's 1976 version of A Star is Born!)

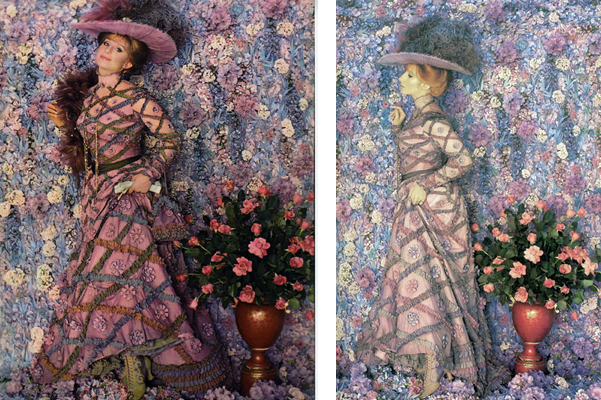

Cover photo by: Gordon Parks

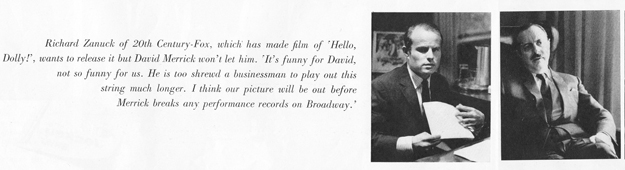

Richard Zanuck of 20th Century-Fox, which as made film of 'Hello, Dolly!', wants to release it but David Merrick won't let him. 'It's funny for David, not so funny for us. He is too shrewd a businessman to play out this string much longer. I think our picture will be out before Merrick breaks any performance records on Broadway.

David Merrick is holding 20th Century-Fox to their original contract preventing release until Broadway run ends. 'They offer money, they threatened to release the picture anyway. They wouldn't dare – there would be a big injunction. Money isn't the issue – we want to break the record for number of performances of a musical on the Broadway stage.'

Even before the feud over the release of "Dolly," the film's course from stage to screen was far from smooth. The author of this account, which is excerpted from his forthcoming book "The Studio," to be published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux, spent a year at 20th and was on the set when the shooting—and troubles—began.

Hello, Dolly!, a musical version of The Matchmaker, which was an updated treatment of The Merchant of Yonkers, which was based on a Viennese trifle called Einen Jux Will Es Machen, which came from an 1835 English comedy called A Day Well Spent, opened on Broadway on Jan. 16, 1964. In March of 1965, Richard D. Zanuck, executive vice president for production at 20th Century-Fox, announced that his studio had bought the film rights to Hello, Dolly! from Producer David Merrick for $2 million plus a sizable percentage of the gross. Written into the contract was a seemingly insignificant clause which stipulated that 20th could not release the film until the play closed on Broadway or until June 20, 1971 —whichever came first. Everybody chuckled as they signed the contract; Dolly! was a hit, to be sure, but 1971—not even My Fair Lady had that kind of run.

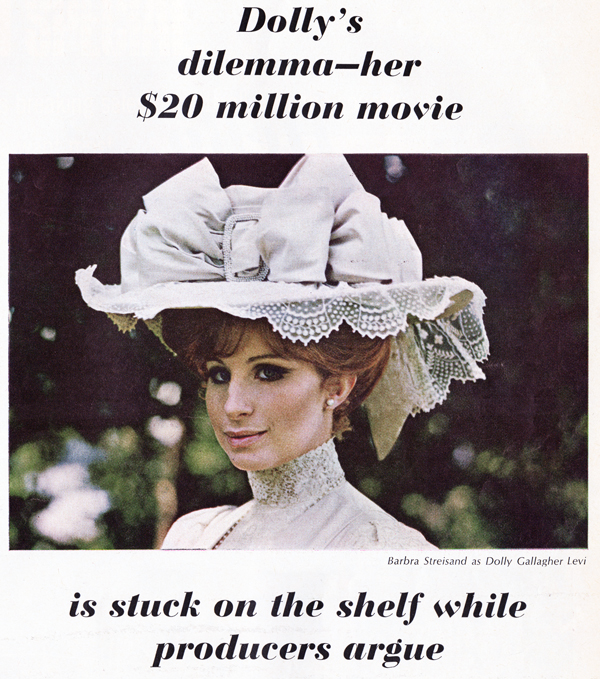

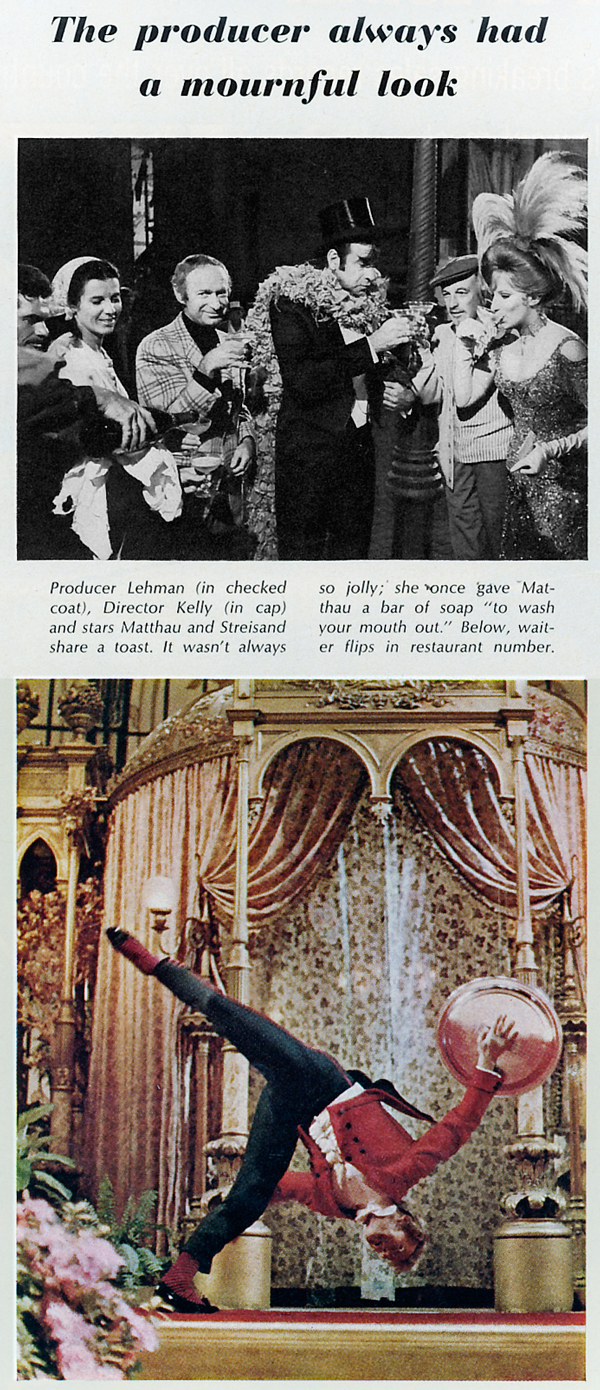

Zanuck allocated a budget of $20 million, making Hello, Dolly! the most expensive musical ever filmed. Barbra Streisand and Walter Matthau agreed to star; Gene Kelly was signed to direct. Shooting began on April 15, 1968 and ended 90 days later—but not before a series of problems (p. 62) that bespoke bigger trouble ahead. The film is virtually finished now. Director Kelly has only a few weeks of polishing left, and Producer Ernest Lehman is already busy on his next film. Zanuck wants to release it as soon as possible.

The catch is that the Broadway Dolly!—revitalized by Pearl Bailey and an all-Negro company—is still going strong, and Merrick has no intention of closing it. He wants to break the My Fair Lady record (2,717 performances) and sees his chance in 15 months. "I'm very fond of 20th," he says, "I sell them all my plays. What's so frustrating to them is that something other than money is holding them up. I don't know what it is — you might as well call it pride."

There was an 89-day shooting schedule on Hello, Dolly!, and at the end of the first week's shooting Ernest Lehman still did not have a completed budget. In his five-room suite of offices Lehman fretted. Worry seems almost endemic to him. He is a slender man in his early 50s with long, graying sideburns and thinning hair arranged artfully across the top of his head. He had been a top screen- writer for over 15 years, several times a nominee for the Academy Award and the recipient of a number of best screenplay awards from the Writers Guild. Hello, Dolly! was only the second picture that Lehman had produced. The first was Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and the disparity between the two projects seemed at times to overwhelm him. "I've got some goddam nerve," he said. "From a four-character picture to this." A pained look crossed his harried face. "You know, there's one sequence where we're going to put out a call for 2,500 extras." He was wearing a checked jacket and a soft white Zhivago shirt and on his wrist he wore a thin gold watch on which the letters of his name replaced the numbers, like this:

"You've got to have 12 letters in your name," Lehman said. "Otherwise it won't work."

He buzzed his secretary and asked her to ring Chico Day, the production manager on Hello, Dolly! "Chico," Lehman said, when Day came to the phone, "how are we doing on the rain insurance?" Hello, Dolly! was supposed to go on location for a month in Garrison, N.Y., and the weather in the east was always a problem. A prolonged rain spell could be prohibitively costly, forcing a company to shut down and adding as much as several million dollars to the budget of a major picture.

"Chico, I need the figures on what it's going to cost," Lehman said. He listened for a moment, his face growing even more mournful. "You can only get it by the hour? Jesus, if it rains, it gets muddy, you can't shoot all day. An hour's rain is going to cost us a day anyway, so let's try and get this insurance by the day and forget this hour stuff."

He hung up the phone and picked up a stack of publicity photographs of himself, examining each one through a pair of glasses without temples that resembled a lorgnette. "Gee, is my double chin as bad as in these pictures?" Lehman said, "patting himself under the chin. "I don't think so." He handed the photographs back to Patricia Newcomb, the public relations woman assigned to Hello, Dolly! "See if they can do something with my chin."

Late that afternoon, Lehman drove his Cadillac over to Stage 14 where Michael Kidd, who was choreographing Hello, Dolly!, was rehearsing the title number with Barbra Streisand. The set was the most complicated interior for Hello, Dolly!, and at $375,000, the most costly of all the inside sets. It was called Harmonia Gardens and was suggested by the more lavish restaurants of New York's gaslight era. Lehman's production designer, John DeCuir, had built the set on four levels: foyer, bar, dining room and dance floor. Fittings and furnishings were burnished gold and ivory, and curtains, upholstery and carpeting were crimson, pink and salmon. There were two large 28- foot fountains, 20 columns, each ringed with a fountain of its own, four domed private dining alcoves and, dominating the set, a huge staircase. It was at the top of this staircase that Barbra Streisand was now standing, chewing placidly on a hangnail.

She was wearing a lightweight muslin version of the beaded topaz dress designed by Irene Sharaff for the Hello, Dolly! number. The purpose of the rehearsal was to see if the dress was functional. Both Lehman and Kidd suspected that the original, still unfinished, was too heavy for Barbra Streisand to execute the high kicks choreographed by Kidd. Standing in the sunken dance floor on the lowest level of the set, Kidd clapped his hands. The male dancers lounging in rehearsal clothes at the foot of the staircase took their positions. Lehman pulled up a stool and perched on it beside Kidd. The music for the number had already been prerecorded and Kidd motioned for it to begin. Beating rhythm with his hands, he said, "Okay, let's take it from the top."

Barbra Streisand began moving slowly down the red-carpeted staircase, mouthing the words of Hello, Dolly!, "Hello, Rudy. Well, hello, Harry." When she reached the bottom of the stairs, the tempo picked up. The dancers swirled around her, circling the ramp above the sunken dance floor. Twice Barbra Streisand tripped over the train of her dress and twice more the dancers stepped on it. The number concluded, after a complete circuit of the set had been made, with Barbra Streisand, all alone, ascending the staircase. Kidd whistled through his teeth for the music to stop.

"The train's got to go, Ern," Kidd said to Lehman. "Maybe we'd better get Irene over here," Lehman said hesitantly. "Sure, Ern, get Irene over here, but the train's still got to go," Kidd said amiably.

A call was put in to Irene Sharaff to come immediately to Stage 14. Lehman fingered the neck of his Zhivago shirt. "Michael, I don't think the number ends right," he said. "I think Barbra should be coming down toward the camera, not going away from it." "No question, Ern, it stinks," Kidd said pleasantly. "What I mean, Mike . . ." Lehman began. "No problem, Ern," Michael Kidd said. "The number's not finished. We're just here to see how the dress works and how the set works." "It doesn't stink, Mike, that's not what I meant." "Ern, the number's not finished," Kidd said firmly.

The stage door opened and Irene Sharaff walked onto the set. Winner of five Academy Awards and a number of Broadway awards for costume design, she was an intense, formidable, chain- smoking woman in late middle age. She was wearing a suede mini- skirt, a foulard blouse and ranch hat, and as Kidd explained the problem with the dress, she sat noncommittally on a stool, puffing on a cigarette.

"Perhaps I'd better see what you're talking about, Michael," she said when Kidd finished. Her tone was deliberate and slightly patronizing. Kidd motioned for the number to be done again. The music began, and as Barbra Streisand and the dancers circled the set, Irene Sharaff twisted slowly on her stool, following their movements. Again both Barbra Streisand and the dancers tripped on the train of the dress. "See what I mean?" Kidd said when the music stopped. Irene Sharaff ground out her cigarette with the toe of her shoe. "No, Michael, I don't see what the problem is."

"Barbra trips on it, the dancers step on it."

"Perhaps if you changed the movements, Michael, the dancers wouldn't step on it," Irene Sharaff said.

Lehman wiped his brow nervously. Kidd seemed unperturbed. "We've still got Barbra tripping on it." "I don't think in the finished dress she will," Irene Sharaff said. "The material is so heavy, it flows much better than the muslin."

"There's another problem," Kidd said patiently. "The dress is so heavy Barbra won't be able to kick at the end of the number."

"But, Michael," Irene Sharaff said as if to a child, "is the kick necessary?"

"I think it is, yeah," Kidd said. He seemed unfazed by Irene Sharaff's recalcitrance.

"The dress will be finished next week, Michael," Irene Sharaff said. "Why don't we wait until we see it on Barbra before we talk about changes?"

"Sure, Irene," Kidd said cheerfully. "And if the dress doesn't work, there'll be some changes made." ' Michael Kidd was also unhappy about the set. The dance floor, the lowest of the set's four levels, was in a sunken well bordered with booths and banquettes that were topped with gaslights and curlicue grillwork. The circuit made by the dancers in the Hello, Dolly! number was to be on the next higher level, around the rim of the well. But much of the number was going to be shot from the floor of the well and Kidd wanted the booths lining the sunken dance floor ripped out. His reasons were that the diners in the booths and the gaslights and the grillwork would all be in the foreground on the shot, detracting from Barbra Streisand and the dancers doing the number immediately above and behind.

With the booths out, the cameras could concentrate on the main action.

"But, Michael, the set is supposed to be a restaurant," said John DeCuir, the production designer on Hello, Dolly! and a winner of Academy Awards for both The King and I and Cleopatra.

"I'm just saying, Michael, that if we take out the booths, then there was no reason making the set a restaurant," DeCuir said.

"And I'm saying, John, that people aren't going to pay $3.50 a ticket to see someone gumming down a lamb chop," Kidd said. He dispatched his assistant, Sheila Hackett, to one of the booths, and then he crouched and squinted in the middle of the well, using his hands as a camera to frame a shot. "See, we've got Sheila right there in the foreground, right? She's a nice kid, but the people aren't paying to see her, they're paying to see Barbra. And Barbra's going to be behind her."

Lehman shook his head in annoyance. "For Christ's sake, why does this have to come up now?" he said angrily. "We had sketches of this set, we had a model of this set, so why didn't you two get together before this? You know what this set cost, you know Stan Hough's on my ass about it, you know we can't spend another goddam nickel on it, and now you're telling me we've got to rip out some booths."

"I didn't say that Ernie," DeCuir said.

"Yeah, well, Ern, John likes to look at people eating," Kidd said.

"Oh, for Christ's sake," Lehman said. He walked off by himself for a moment and then came back and asked DeCuir if it were possible to pull out just a few of the booths and not all. DeCuir shook his head. "I'd have to pull them all out, Ernie, and then put in an apron that comes out about six inches from the present facing," DeCuir said.

"Why that too, for Christ's sake?" Lehman said.

"We need the apron, Ernie," DeCuir said. "No camera operator is perfect. If his camera jiggles, you're going to pick up the facing, and without the booths, what is there? Nothing. The apron gives us something in front of the dancers' feet, so if the camera does jiggle, we've got some floor space to show."

Lehman slapped his palm on a stool. "Well, can't we have some shots of people in the booths?" he said.

"Sure, Ern, no objection," Kidd said. "We can establish it, we can have a couple of angles shooting up through the booths. Then we take out the booths and shoot the rest of the number."

Lehman looked unhappy. "Find out how much it's going to cost," he said to DeCuir. "And then I'll call Stan Hough. I don't want him on my ass Monday. Let's get him on my ass now and get it over with."

END.

Related: Hello, Dolly! Film Page

Gordon Parks Photo Outtakes

Below are alternate shots by Gordon Parks, the photographer who captured the cover image of Streisand.