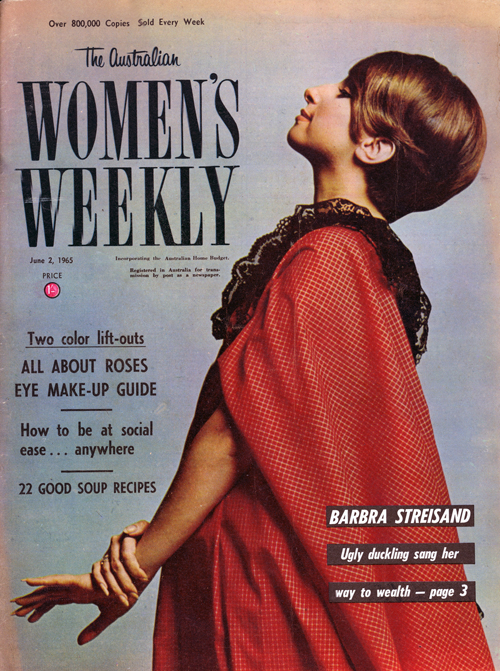

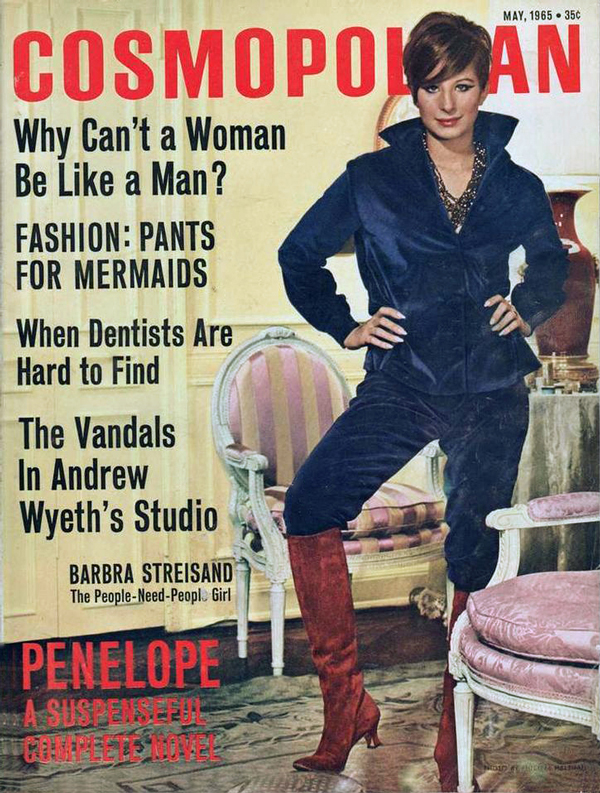

Cosmopolitan Magazine / Australian Women's Weekly

May 1965 / June 2, 1965

* both magazines contain the same text; photos on this page are from the Australian magazine.

Barbra Streisand: The People-Need-People Girl

by Liz Smith

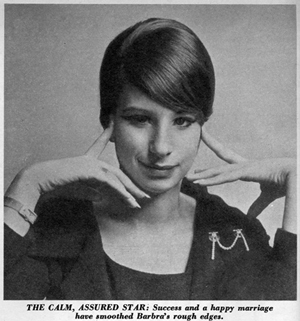

Riding the crest of one of the biggest popularity waves in theater history, the twenty-two-year-old kid from Brooklyn—now more calm than kooky—revels in the joy of Funny Girl stardom, but holds to marriage as her greatest success.

The worst, absolutely lowest, most impossible thing about success to Barbra Streisand, the unprecedented star of 1964-5—and for all we know, future generations—is to be interrupted when eating. The twenty-two-year-old Brooklyn-born and Broadway reborn skyrocket sat quietly in her newly decorated living room which is filled with f. F. f. (fine French furniture) and extolled the sacred rite of eating in peace and quiet.

"The other night I was dying to go to Leone's—you know, they sit you down at a table with a big hunk of cheese and fruit and raw vegetables and breadsticks. But I hadda go there on the night of a festival. The place was jammed and even though the food was great—listen, they brought us hot chestnuts after, which flipped me—people kept coming up in a stream all through dinner and saying that same thing over and over: 'Listen, I hate to bother you, but will you sign this?' I wanted to say to them, 'If you hate to bother me, why do you? Why don't you just admit that you know you're bothering me and don't care?'

"To be disturbed when you're tryin to eat—that's awful," said the owner of a ten-year, multimillion-dollar contract with CBS, the girl who has won unparalleled concessions from a major network. She just refused forty-five thousand dollars for a one-night stand (highest fee offered anybody for a single envening's work). She stars in Funny Girl, Broadway hit amalgamated almost entirely of her unique personality and mystical talent in reviving the legend she so resembles—that of Fanny Brice.

Barbra and her young husband, Elliott Gould, have tried to get organized since she shot to fame last May. They find it easier to stay home than cope with Barbra's teeming fans, or to go someplace like "21" where they know they will be protected. "I do dig the steak Diana and chocolate soufflé at "21," said Barbra, "and who would bother you there? In that place everybody is somebody. If I'm not careful, I might go up to a table there and bother somebody myself."

I asked her if eating at places like "21" had reversed her verdict that the best hamburgers are only available in luncheonettes. "Oh no, the meat is too good at places like "21" and the hamburger patty is too thick. White Tower is still the best, or Chock full o' Nuts. There's a new White Tower open all night on Forty-sixth Street and we go there; also a Snacktime on Thirty-fourth Street near Eighth Avenue. I sit in the car and Elliott brings me hot buttered corn on the cob."

Just in case, the refrigerator in the modern kitchen of their dream duplex way up on Central Park West is kept stocked with TV dinners, coffee ice cream and the other exotica of prepackaged dining. But the Goulds have come quite a long way from the chaotic life they were reported leading at the moment of Barbra's initial big impact when both Life and Time had her on their covers and everybody in the world was rushing to analyze her, describe her and predict that her Hansel-and-Gretel marriage couldn't last. Nowadays, Barbra and Elliott are better organized and life is nicer. The apartment is "getting done"— its pale mauve flocked entrance hall a triumph—its formal and sterile living room and dining room finished though looking unlived in—its celebrated bedroom upstairs now completed with a chartreuse carpet covering the mounted approach to the canopied bed, the profusion of attractive pillows and the stunning fur coverlet. Only the terrace, looking out over Central Park and around at the Hudson River, needs sprucing up, and the soft burgundy-colored den with its grand piano is unfinished. These days, a housekeeper, Mary, takes special care of the Goulds and even cooks for them— leaving after-theater treats such as fillet of sole stuffed with salmon, baked in sour cream and topped with almonds.

There are plenty of other changes around Barbra these days. Stardom achieved and savored for several months has smoothed off her own rough edges, calmed her down, given her a chance to accept herself. Now she is quiet and warm. "One changes normally all the time, of course," she said, "but now I am more relaxed, less quick to judge, much less defensive. I hope I've lost that grasping quality, the overemotionalism."

It was a sunny crisp day when I taxied up Central Park West to see Barbra. She was in the beginning of plans for the first of her television specials, My Name Is Barbra, to be seen April 28th. On a Victorian sofa in the entrance hall lay a black mink cape, lined in the same maroon print fabric as the upholstery of the sofa. Barbra had just come in from seeing the doctor. She was wearing a bulky V-neck maroon sweater (shades of maroon, mauve, burgundy, pink, dusty rose and red seem to be her favorites), gray jersey stretch pants tucked into short black boots and no jewelry except a platinum wedding ring.

Coiffures by Barbra

I was surprised to find she had cut her hair off—it was sliced across her head in a kind of reddish-brown cap which revealed elfinlike ears. She pooh-poohed reports that she is the customer of a New York name salon. Her hairdresser is that little old beauty operator Barbra. "You know I had my hair cut sometime ago in an ordinary beauty shop in London, shorter in back than on the sides and when I came back here the whole Vidal Sassoon fad was just beginning. Then I found a wonderful guy in Chicago named Fredrick Glaser—he was so neat, such a perfectionist—so now whenever there is some big deal, I have him fly in. But otherwise, I tend to it myself."

She was carefully undermade-up except for the eyes which were generously outlined and about the bluest I've ever seen. Her generous mouth glistened with a natural lip pomade and her nails were glinting and silvery. I have never seen anybody look quite so spotlessly clean, young and disarming. This is a girl some of the world's best reporters have come to see—writing down her offbeat remarks, falling under her spell, telling her after a few hours or days' observation how beautiful she really is and how everyone else has missed her essence. "Then," she laughed, "they go away and describe me as an anteater—all the same old things about the nose, the ugly duckling, the Cinderella bit, etc. My mother, who still doesn't quite believe what has happened to me gets furious and I think ... I'm afraid, she tells them off. Somebody wrote I had Fu-Manchu nails and she dashed off a letter signed 'Barbra's mother.' Imagine what they thought when they got that!"

Her contract for Funny Girl runs through December. After that, what? "I'd like to have a baby, or take a vacation in Europe." She said she would probably eventually make a film of Funny Girl, and then there are the television spectaculars. "In My Name Is Barbra," she said, "there was debate whether I should do it by myself. Some people run scared, you know what I mean? They thought I needed help. But I'm doing it alone. There's a section where I'll do children's songs, a dream bit in a department store, a kind of regular concert part— Oh yeah, I'm going to sing 'My Man.' Everyone expected me to sing it in the show and I couldn't, so I'll do it on TV." The spectacular is being managed out of the Goulds' East Side Ellbar Productions office (an amalgam of her name and Elliott's) which is hooked up to the duplex by a special phone that occasionally squawked during our visit. I asked how she felt at wresting such publicized concessions from CBS.

"I didn't think of it that way," she said simply. "I was concerned with artistic control only. I wanted to produce my own shows and now I can and nobody— not sponsors or advertisers or anyone— can interfere. The people like Dick Lewine, Joe Layton, Dwight Hemion and Marty Erlichman—they are on my team. They're for me and what I want to do."

We talked awhile about what she might tackle later in the theater. "Have you a secret desire for Hamlet or something like that?" I asked. She brightened. "I'd love to play Hamlet. I'd also like to play Juliet. What was she really like? You could bring so many facets to it— the fact that she was an only child, a spoiled brat. . . . It's good that Romeo and Juliet died —otherwise nothing."

The Peripatetic Reader

A new copy of Gray's Anatomy of the Human Body and How to Be a Jewish Mother were huddled together in the bookshelves being built in the den. Did she read a lot? "I go through different periods and then I get fed up." She shrugged. "I'm reading about ten books at once now." Barbra gives the impression that her tastes are energizingly eclectic and changing at the speed of light. Famed as a fur-coat collector, she couldn't think offhand how many she had, but said, "I don't like total fur anymore. I'm sick of fur coats now. A cloth coat with sable cuffs would be delicious. But I'm tired of mine. I'm going to cut them all up into cuffs. A few weeks ago I liked fur on fur, but now . . . Hey, that sounds terrible. What would the Russians say about that—decadent?"

I told her I thought extravagance was justified by the vicarious experience it gave to others. She liked that and she began to discuss money. "Well, once I got fifty dollars a week allowance but that was too much for me. Now I get twenty-five dollars. I use it for cabs and tips and it's great not to have to think about the important things I buy— charge it, send it, send the bill to my business manager—you know. As for the bill money coming in, every once in a while I decide I want to know everything about it. So there is a meeting and people come in and show me the figures. It's fun, but then I go through phases when I don't want to know anything about it.

"My real interests now are studying Italian and learning to play the piano. I called Lenny Bernstein up and he recommended this teacher for me. She gives me very hard stuff to do, but it appealed to me because I love math and music is like a mathematical problem. My teacher, Shirley Rhoads thinks I'm a genius.

A Den of Antiquity

It wasn't hard to believe that Barbra was good on the grand piano in the den. The room more nearly expresses her past personality with its cluttered boxes, and brass hat tree covered with plastic-covered hats, a cabinet full of satin and gold shoe buckles, an old stand-up telephone. A depression-era purple Spanish shawl with black fringe covers the piano and on top of that stands a sepia-toned picture of a younger Barbra, age seven or eight. There is the beginning of the famous Streisand nose, a faintly smiling mouth, sad little girl eyes. A few years later at twelve, she gave her first and only amateur performance prior to discovery in 1961—a recording her mother had Barbra make of "You'll Never Know." "I still have the record," said Barbra. "I even improvised on the end."

I thought of the photograph on the piano. From that Brooklyn sapling had sprung the mightiest new oak in show business. Why did she happen when and as she did—what did she feel it told of society that her success was so sudden, so all-embracing?

Barbra thought. . . . "People were just ready for me. Music was predominantly rock 'n' roll and there was no other major new artist around so when I came along and did my esoteric, ethereal songs, I think people were struck by my audacity. The songs were pretty, too, and they had to like those for themselves. I mean they had quality—like Rembrandt. How could anyone not like them? And then I think maybe they asked, 'Who is that girl?' You know ..."

Streisand in performance has been overdescribed, compared ad nauseam, and made to bear incredible examples. She is simply one in a million who comes on stage with such riveting conviction and dynamism that there is no escape from her compelling attraction. I asked, does she control her audiences or do they control her? "We work together. But on my good nights, I do control them, and on my bad nights, they control me. I think an audience has to be led and I can make them laugh or not. I test it all the time. I know my talent is not a gimmick, but I have to be good now all the time, because once you are established then comes the hard part. You are always on trial and being judged.

"It's funny because you can't relax. I'm kept away from a lot of what goes on in connection with my so-called success. I just can't stand sometimes to even know what my obligations are— they seem so formidable. In a way I have more now, the movie, television, concert offers, the records. When the new wears off, you have to really be there."

We talked of the talent contest Barbra won only short years ago at a place called The Lion in Greenwich Village. "A friend, Barry Dennen, told me about it. My unemployment insurance was up and though I'd never sung anyplace or done anything, I decided to try. From there the owner Burke McHugh took me to the Bon Soir, then I went up to the Blue Angel and Merrick put me into I Can Get It for You Wholesale—well, you know the rest." I reminded her of a dress she wore in the Bon Soir—a long red jersey tube. "Oh yeah, someone gave me that so I guess I thought I had to use it."

Barbra and Elliott don't go out much or socialize though naturally they could be as lionized as they like. (Their best friends are not in the arts—Dr. and Mrs. Harvey Corman.) They can take their acting contemporaries or leave them. "It's very difficult to be around actors— that concentration of ego. They're not interested in too many things. The theater is only one small part of life," said Barbra. She and Elliott are so close, I asked if his Brooklyn background had anything to do with that. She was emphatic. "No." What did they do for amusement? "We eat and watch television. We have this new color television and are always watching old movies."

I asked Barbra how motion pictures had influenced her. "I don't know. I like pretty women and handsome men, so for the movies I was a real believer. I could be depressed for days after seeing something." We spoke briefly of the Burtons because when Barbra and Richard were both up for the Tony award and failed to win, he had called her up after to say "What a shame luv, you deserved it." I told her I wanted to ask her the same question I had once put to him—what is she afraid of?

Bugaboos in the Closet

She cast about. "What did he say? Oh, death—well, that's obvious. I don't know, I'm afraid of everything—closets, wire coat hangers, the dark, the unknown.

"Religion? People have a need to believe in something in this kind of world where a bomb can fall and end it. You have to either kill yourself or try to accept life and live civilly. You know, realize that terrors exist, but not let them stop you from trying to make the best of your own life. I like the Eastern religions because they accept death as part of life—there is something I like about that. So when I have a need for religion I use it; I don't go to church or synagogue. It's just a personal thing with me.''

She launched into something about Indian women having babies and bearing pain without making a fuss and ending up part of the earth. I didn't quite get it all down because she fascinated me so as she talked, ranging between youthfulness and a kind of Oriental wisdom. I found I had to agree with fashion writer Eugenia Sheppard who was the first to put the kibosh on the overrepeated, kooky-cult analysis of Barbra. Miss Sheppard had said in the Herald Tribune: "Barbra is anything but kooky. She's only about as kooky as Gloria Guinness, C-Z Guest, the Duchess of Windsor or any of the all-time fashion greats were when they had just turned twenty-two."

Barbra was delighted. She said this was one of her favorites of all the things ever written about her. "I took it as a big compliment and I thank her so much for it. That kooky thing is so tiresome. Nothing that is kooky can really mean anything or stand up."

I read about some of the delightful things her handsome actor-husband has said about her. "I often think of Barbra as forty-six, going on eight. . . . She reminds me of a combination of my two favorite people: Sophia Loren and Y.A. Tittle ... a beautiful flower ... She is my woman but everyone wants her ... I found her absolutely exquisite. I had this desire to make her feel secure." Could Barbra possibly describe him as well as he has described her. "No," she said, but then indicating that she would try she turned almost shy. Obviously we were on dangerously tender ground. I felt she almost might cry if I pressed, so I was silent. Finally she said, "Elliott —I have to put an underline under it and then go [marking the air with her fingers], Elliott, with two l's and two t's. He does it so great with me but I can't begin to do it for him. To me he is a mixture of Bogart, the Michelangelo statue of David and Jean-Paul Belmondo."

A Taste of Security

"Does he take good care of you?" I asked, caught up in the spell—realizing that after all this was a young twenty-two-year-old wife, very much in love with a tall good-looking husband, living in her first taste of real security both professionally and privately, the first home of her own, the first emotional life of her own. It was beside the point that for the past ten minutes the den had been filling up with the brusque sounds of businessmen. I saw producer Dick Lewine shuck his coat in the hall and go inside. Someone ticked off a sound on the piano. Thousands of dollars worth of show business brains were waiting for Barbra to finish her talk with me and come switch them all on.

"Does he take care of you?" I asked again. "Yeah," she said softly. "Yeah, he sure does."

END.

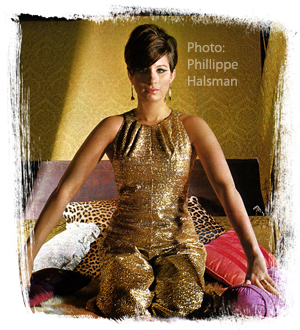

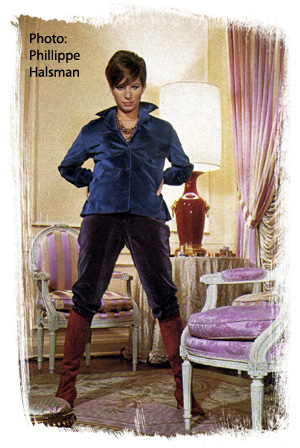

Photo Session Outtakes

Phillippe Halsman photographed Streisand in her Manhattan residence for Cosmopolitan Magazine. Here are a couple of outtakes from the session: