Barbra Streisand Sets the Record Straight

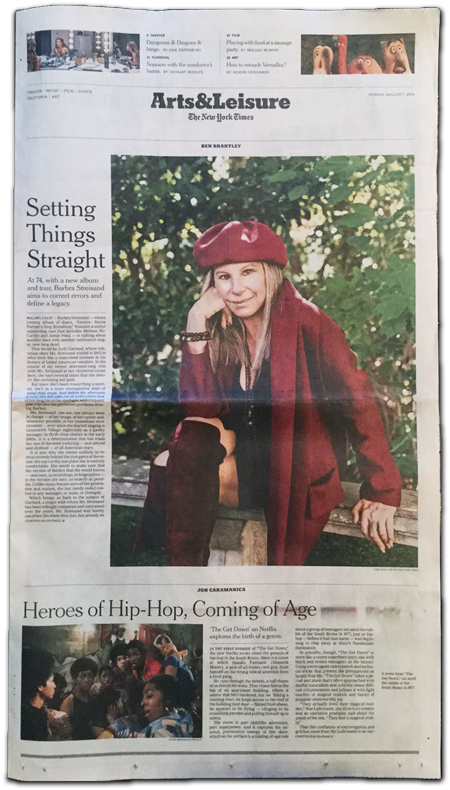

At 74, as she embarks on a memoir, an album and a rare tour, the megastar is intent on correcting the tiniest) errors and on defining her own legacy.

By BEN BRANTLEY

AUG. 3, 2016

Photos by Emily Berl

Barbra Streisand — whose coming album of duets, “Encore: Movie Partners Sing Broadway,” features a stellar supporting cast that includes Melissa McCarthy and Jamie Foxx — is talking about another duet with another celebrated singer, now long dead.

That would be Judy Garland, whose television show Ms. Streisand visited in 1963 in what feels like a watershed moment in the history of fabled American vocalists. In the course of my recent afternoon-long visit with Ms. Streisand at her cloistered estate here, she says several times that she doesn’t like revisiting her past.

But since she’s been researching a memoir, she’s in a more retrospective state of mind than usual. And before the afternoon is over, she will take me on a circuitous tour of her long life in the spotlight, with frequent side trips into the persistent problems of being Barbra.

Ms. Streisand, you see, has always been in charge — of her image, of her career and, whenever possible, of her immediate environment — ever since she started singing in Greenwich Village nightclubs as a gawky teenager in thrift-shop clothes in the early 1960s. It is a determination that has made her one of the most enduring — and adored and disliked — of all American stars.

It is also why she seems unlikely to retreat entirely behind the iron gates of the estate she says is the one place she is entirely comfortable. She needs to make sure that the version of Barbra that the world knows — onscreen, in recordings, in biographies — is the version she sees, as exactly as possible. Unlike many female stars of her generation and stature, she has rarely ceded control to any manager, or mate, or Svengali.

Which brings us back to the subject of Garland, a singer with whom Ms. Streisand has been tellingly compared and contrasted over the years. Ms. Streisand was barely into her 20s when they met, but already on the cusp of astronomical stardom; Garland, 41, would be dead six years later, one of Hollywood’s most notorious casualties of devouring fame. Yet when they sang two American standards in counterpoint — “Happy Days Are Here Again” (Ms. Streisand) and “Get Happy” (Garland) — they seemed like a matched set.

Each interpreted an upbeat song with a big, trumpeting voice that nonetheless hinted at a small, solitary figure within. Happiness, as hymned in these renditions, would never be won easily. You can find that video on YouTube, and it is impossible to watch it without shivering.

“Afterward, she used to visit me and give me advice,” Ms. Streisand says. “She came to my apartment in New York, and she said to me, ‘Don’t let them do to you what they did to me.’ I didn’t know what she meant then. I was just getting started.”

Whoever “they” were — studio moguls, a voyeuristic press, parasitic hangers-on, cannibalistic fans — it was never likely that they could do to Ms. Streisand what they did to Garland. From the earliest days of her career, Ms. Streisand exuded a Garlandesque fragility and emotional openness. But her long nails and close-set eyes, both quizzical and confrontational, spoke of the toughness of someone singularly capable of protecting herself.

Both sides of that dichotomy are still very much in evidence when I visit Ms. Streisand at her estate here, a compound of three main buildings that evoke a fantasy New England, incongruously situated above the glittering expanse of the Pacific Ocean. To step behind its gates after experiencing the brown and smoke shades of the adjoining highway on a hazy summer’s day is to feel like Garland’s Dorothy stepping from sepia-toned Kansas into the Technicolor of Oz.

Ms. Streisand — who is promoting both her album, due Aug. 26, and her nine-city concert tour this month (called “The Music … the Mem’ries … the Magic!”) — is waiting at the open door of the house she lives in. That’s as opposed to the one she works in — called “Grandma’s House” — or “the Barn,” which she describes as “an art project.” That’s the one with a subterranean mall of old-time shops, a jaw-dropping marvel of themed décor and room after room of impeccably arranged artifacts.

Below: Barbra Streisand in her dressing room at the Winter Garden in 1964, during her Broadway run in “Funny Girl.” Credit John Orris/The New York Times.

At 74, she looks like, well, Barbra Streisand, albeit a softer, more subdued version than the one you know from six decades of movies, from her Oscar winning-debut in the musical “Funny Girl” (1968), in which she recreated her Broadway performance as the Ziegfeld entertainer Fanny Brice, to the comedy “The Guilt Trip” (2012), with Seth Rogen. Though the rooms behind her beckon in carefully coordinated shades of pale, Ms. Streisand is wearing the uniform black of an East Coast urban dweller.

“I am a New Yorker!” she exclaims, when I point out the discrepancy. “A Brooklynite. That means it’s an earthy place to come from. It’s reality, as compared to reality TV.”

In conversation, she is a paradoxical mix of wide-open spontaneity and preoccupied vigilance. She may shoot from the hip when she talks about herself, but she also backtracks a lot, as if to retrace the bullet’s trajectory and make sure it hit its target. It’s when she’s guiding me through her homes — gleefully annotating their contents (while noshing from the plates of garden-fresh snacks that keep materializing, courtesy of her longtime housekeeper) — that she seems most at ease.

Ms. Streisand has created her own sui generis alternative reality here, one she shares with her husband, the actor James Brolin. (On this afternoon, the day before their 18th wedding anniversary, he is filming a movie in Canada, but he has sent her “four beautiful arrangements of flowers.”)

Below: Barbra Streisand at her Malibu, Calif., home.

This world is arranged and maintained according to her highly exacting standards, though even here there are annoying signs of imperfection. “Vicky, whose truck is that?” she calls out to an assistant, as she’s showing me her rose-thick gardens. “It’s in the shot. Whenever I show my house, I never want a car in it. Also, tell somebody there’s a mop in the lavender room in Grandma’s House.”

Ms. Streisand has written a book about the creation of this private Xanadu, “My Passion for Design,” which became the unlikely basis for a play about her, Jonathan Tolins’s “Buyer & Cellar.” No, she hasn’t seen it. One of the first things she says to me, chummily, is “I understand you’ve seen ‘Buyer & Cellar’; well, now you can see the real thing.”

Ms. Streisand says she hates to leave her Malibu property, the place where she can be in control. Almost as soon as she set foot onstage, during rehearsals for her first Broadway show, “I Can Get It for You Wholesale,” she has known, she says, that she was born to be a director, in all senses of that word.

She has become one behind the camera, as the pioneering female director, star and producer of “Yentl,” “The Prince of Tides” and “The Mirror Has Two Faces.” Being that kind of director, though, means waiting — and waiting — for green-lights and money and rights to material. Though it had been announced a few weeks earlier that she would be making her long-anticipated version of the musical “Gypsy” — in which she would portray the ultimate stage mother, Mama Rose — that project is again in limbo.

“I’m at their mercy,” she says. “One day you’re going to do ‘Gypsy,’ the next day it’s off. And then this is the only place — writing a book, making a record or doing a tour — where I can do what I have to do, my work.”

The record is “Encore,” the 35th of Ms. Streisand’s studio albums. (To date, her records have sold about 245 million copies worldwide; and with “Partners,” her 2014 compilation of duets, she became the only singer to land a No. 1 album in six successive decades.)

She says that working on the numbers with the other singers — performers known principally for film work, and including Antonio Banderas, Alec Baldwin, Anne Hathaway and Seth MacFarlane — was rather like producing a series of mini-movies. She added dialogue and, in some cases, altered lyrics from Broadway classics.

For her interpretation of Irving Berlin’s “Anything You Can Do,” from “Annie Get Your Gun,” she devised a prologue in which she and Ms. McCarthy sparred after learning they were up for the same film role. This allowed Ms. Streisand to interject a joke about how to say her name: It’s Streisand, as in “sand on the beach,” not “Strize-and,” a mispronunciation that has plagued her at least since she first appeared on “The Ed Sullivan Show” in the early 1960s.

Recently, she heard John Mayer (with whom she sang on “Partners”) being interviewed by the producer and TV host Andy Cohen, and to her dismay, “they both called me Barbra Strize-and.” She says she can’t wait for them to hear the duet with Ms. McCarthy. “Maybe they’ll get it now,” she says, managing to sound both amused and annoyed.

The world is riddled with such exasperating errors, and Ms. Streisand sees herself as burdened with the Sisyphean task of uprooting them. Working on her memoir — scheduled for publication in 2017 (although she says, “Don’t hold your breath”) — she has become more agonizingly aware than ever of misrepresentations in the many, many accounts of her life that already exist.

Writing about herself is not a process she enjoys. She says if she can speak fluently these days about long-past events, it is “only because I’ve had to look it up.” She is grateful to have discovered the existence of the superfan Matt Howe’s online archive of all things Streisand.

Not that she looks at it herself. “Because, again, it’s like the play [“Buyer & Cellar”],” she says. “How do I look at myself? I can’t do it. But my researcher tells me what’s on that thing, like Marvin Hamlisch singing ‘The Way We Were’ [the theme song of her 1973 hit movie with Robert Redford] before I changed the melody and some of the lyrics.”

For someone like me, who came of age watching and listening to Ms. Streisand in the early years of her career, her forced focus on the way she was is a godsend. It means that I get to see, in the screening room in the Barn, Ms. Streisand’s uncut sequence of herself as Fanny Brice performing “Swan Lake” in “Funny Girl.” (She supplies a running annotation as we watch, which includes speaking, in character, the unrecorded dialogue that Fanny was saying onscreen.)

I also get to hear about the Rialto of yore, where, as a young woman just a few years out of Erasmus Hall High School in Brooklyn, Ms. Streisand became a star in two musicals, “I Can Get It for You Wholesale” (1962) and “Funny Girl” (1964), the first and last Broadway shows in which she has appeared.

When Ms. Streisand showed up at the Tony Awards in June (to present the award for best musical to “Hamilton”), it was her first appearance at the ceremony in 46 years. She never intended to make her career in live theater, she says. For one thing, she hated making the rounds of casting offices (“I’ve never wanted the humiliation of having to ask people for jobs”).

There’s something, she says, about being judged — live and on the spot — that unnerves her, especially since her appearance in Central Park in 1967, when 150,000 people showed up and she forgot lyrics onstage. Since then, “I always got frightened when I had to perform live.” She was absent from commercial concert stages for the following 27 years.

“I’m killing myself for this tour, because there’s a painting I want,” she says. She is a self-described “auction freak,” and the covetable paintings in her house include works by Munch and Modigliani, as well as a portrait of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart. (She performs at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn on Aug. 11 and 13.)

She says she never sings a song the same way twice, which presented problems when she worked on Broadway. Her habit of continually tweaking her role as Miss Marmelstein, the overworked secretary in “Wholesale,” provoked its director, Arthur Laurents, into criticism that stings her to this day. “He said: ‘You’re never gonna make it in showbiz. You’re too undisciplined. You never do it exactly the same way.’”

Ms. Streisand says she visited Laurents — who also wrote the screenplay for “The Way We Were” — not long before he died in 2011. “And I said: ‘Arthur, what do you feel now about the way I work? Do you understand why I change things, or had a hard time freezing the same thing?’ He said, ‘I absolutely do understand.’ That was very rewarding for me.”

Though she had no previous Broadway experience at the time of “Wholesale,” Ms. Streisand had her own specific notions about the staging of it. And for the record, she says, the idea of performing her character’s big solo in an office chair on wheels was hers, not the choreographer Herbert Ross’s.

She seems to look back on her younger self with a certain wonder. “I don’t know that I would have the chutzpah now,” she says.

But where did that original immense confidence — and hunger — come from? Much has been written about Ms. Streisand’s Brooklyn childhood: the gap left by the death of her father, a scholar and schoolteacher, when she was a toddler; the mother who never complimented her and thought she should become a secretary. (For the record, that’s how the signature nails came about, since they kept Ms. Streisand from being able to type.)

“She had talent,” she says of her mother, who worked as a secretary but who Ms. Streisand describes as also having had “a beautiful voice.” “She didn’t have the drive. I said, “Why didn’t you do this, why didn’t you go after your dream?’ You know what I’m saying? You can have a dream, but how do you manifest it, how do you make it happen? Hard work, heart, taking chances — that was always my philosophy.”

It’s all the more surprising, then, when Ms. Streisand says: “The thing is, I was always kind of lazy. On the one hand, I am — or I was — ambitious. On the other hand, if I was having a great love affair or something, I’d say, I don’t want to do anything else. I mean, searching for personal happiness was more important.”

That is why, she says, she turned down a number of plum roles in her first decade in Hollywood, including the starring roles in “They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?,” “Klute” and “Julia.” Those all went, memorably, to another actress. As Ms. Streisand says, in a deadpan aside, “I made Jane Fonda’s career.”

So will we ever get to see her as Mama Rose in “Gypsy”? Ms. Streisand is now several decades older than that character, modeled after the mother of the celebrated stripper Gypsy Rose Lee. But when you hear her talk about “Gypsy” — and to see the project-pitching “sizzle tape” she made, which ends with a concert performance of her defiantly singing the climactic number “Rose’s Turn” — the mouth still waters.

Ms. Streisand has given much thought to Rose. She has talked to her friend Stephen Sondheim, the show’s lyricist, about potential revisions to the songs. She has an ace idea for the delivery of the broken words “mama, mama” in “Rose’s Turn,” based on her belief that the key to Rose’s blind ambition to make a star of her daughter can be found in the mother who walked out on her.

Another description Ms. Streisand offers of Rose seems closer to self-portraiture: “I think she’s tough as nails, but a tough person who’s vulnerable inside, you know? It’s like a crab, something that’s jelly inside. What makes for anger is also hurt, and that gives you the depth of playing somebody like that.”

The Malibu residence, as tailored to her tastes and needs as a couture dress might be, would seem to offer a place where a person might shed her shell. I ask her if she feels serene here. She doesn’t answer immediately. So I ask: “Do you ever feel serene?” “That’s a good question,” she says.

So I ask it again. Her muttered response: “No, not really, sad to say.”

Correction: August 7, 2016

A cover article this weekend about Barbra Streisand’s efforts to define her legacy — including her determination to correct even the tiniest errors about her life — contains several errors. The article misstates the point in her career at which Ms. Streisand met Judy Garland, whose television show she visited in 1963. As the article correctly notes, Ms. Streisand is 74, so she was barely into her 20s at the time, not barely out of her 20s. The article also misstates the surname of the playwright of “Buyer & Cellar,” a comedy about Ms. Streisand. He is Jonathan Tolins, not Tolin. In addition, the article refers incorrectly to Ms. Streisand’s personal collection of artwork. She does not in fact own a painting by James McNeill Whistler. And an accompanying picture caption misstates the year Ms. Streisand is shown directing the film “Prince of Tides,” in which she also starred. The film was released in 1991; the image is not from 1994.

Photo Outtakes by Emily Berl

End.