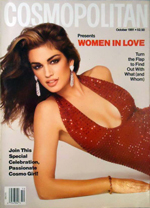

The Triumph of Barbra Streisand

Cosmopolitan

October 1991

As the long summer afternoon winds down, Barbra Streisand ratchets up her psychic mainspring. Several details, domestic and otherwise, have to be dealt with before she can leave her house—a big Spanish-style affair on a hill several blocks above Sunset Boulevard—and drive across town to a test screening of her new movie.

Not that the producer, director, and costar of The Prince of Tides seems tense. Intense, yes; details are her daily bread, at least when she's working. But the diet becomes her. As she hurries from room to room (rooms change suddenly in this house; the decorating virus that afflicts Streisand seems to return, like malaria, without warning), she looks a decade younger than her forty-nine years. Her luxuriant light- brown hair frames a face that bears no signs of retouching; and in leggings and a blue-green silk blouse, her body is slim, lithe.

From a combination sitting room-office done entirely in white, she puts in a call about the retrospective of her thirty-year recording career that Sony/Columbia plans to release this Christmas as an elaborate boxed set. The issue to be settled is at what precise point, on the last of more than fifty cuts in the compilation, will Barbra Streisand begin singing a dual-track duet with Barbara Joan Streisand, an ardent thirteen-year-old songbird on a scratchy home recording made in 1955? Measure for measure on the phone, Streisand discusses the song, “You’ll Never Know,” and makes her final — or at least semifinal — decision.

Next, she goes down to her basement art-deco projection room to check out a new sofa that arrived half an hour before. The sofa is fine, a comfortable replacement for a venerable backbreaker, but new pillows of different lengths will have to be made for the arms—one fourteen inches wide, the other sixteen or eighteen inches—before Streisand can decide whether the arms themselves should be extended three inches. Tapping a tabletop lightly with her long nails, she contemplates a stunning silver-framed nude from the 1920s that stands in a corner, and wonders if it shouldn’t go up there, in the middle of the left-hand wall. Then she rearranges a crystal ashtray and several other bibelots, as if there were only one consecrated way for the objects to be displayed. When I tease her about her obsession with such details by suggesting she shoot a Polaroid of her little chotchke composition, the way they do on movie sets for scene-matching purposes, she says ruefully, “Don’t laugh. I’ve already done that in the living room.”

En route to Columbia Pictures, on the old MGM lot in Culver City, Streisand sits in the back of a Mercedes sedan driven by the husband of her old friend Cis Corman. She talks with Cis, who runs her production company, Barwood Films, about freezing a specific frame—from a love scene between Barbra and costar Nick Nolte— for a print ad. The two women also discuss release dates for the movie; Columbia, starting to smell a hit, is thinking about holding it for Christmas, while Streisand wants to get it out sooner and end the suspense. (The final decision is for a Christmas release.) At the studio, she climbs an exterior stairway alongside the Cary Grant Theater to her second-story editing room, where she works for a few minutes with her editor, Don Zimmerman, on a suspenseful scene, involving Nolte and a Stradivarius, that she feels could use a little fiddling with to make it play faster. As temporary splices on the work print crackle through the editing machine, the director finds herself confronted with tough choices. Through no fault of the actor's or her own, the focus is soft on several takes; in this highly technical medium, the highest law is always Murphy's. “Some of Nick’s best line readings are out of focus,” Barbra says, shaking her head slowly. “It’s all a compromise.”

An assistant says the screening is ready to start, so we go downstairs again. Among the audience of three hundred are a few friends and some Columbia marketing executives, but most are regular people off the street. Streisand tiptoes into the back of the darkened auditorium, feels her way up four steps to a mixing console, and as the screening begins, rides gain on the audio levels; at a screening the night before, she’d kept the volume on Nolte’s voice-overs too high, and she doesn’t want to make the same mistake again. When this screening ends, the audience cheers, but Streisand doesn’t know it, because by then, she’s back upstairs, waiting to host a small reception in her editing room. Soon, friends begin filing in, among them Shirley MacLaine and lyricists Alan and Marilyn Bergman. The expression on the hostess’s face is one of unabashed expectation: Was it wonderful? Did you love it? Yet the first words out of her mouth are “Tell, what didn’t you like?”

Her friends tell her—as friends will — what she wants to hear: The movie is wonderful; she’s lovely in it. (Shirley MacLaine also congratulates her for having cut the right things out: “That’s your brilliance. At least half of it.”) But all of their praise happens to be merited, and then some. Having demonstrated her command of the medium in the radiant, deeply felt Yentl, which she directed eight years ago, Streisand has surpassed herself with a film of greater sweep and even deeper feeling. And although she is lovely indeed in the part of psychiatrist Susan Lowenstein, her finest achievement is her direction of Nick Nolte in the central role of the tortured Southerner Tom Wingo. lt’s a breakthrough performance if ever there was one — a classic of American movie acting.

Eight years is a long time for a director to go between gigs, even if Streisand does have other work to fall back on. It could be argued that she’s always directing something, whether it’s movies, sofa pillows, ashtrays, concert stagings (though she has never liked singing in public and may not ever do it again), or displays of her collection of art-nouveau antiques — which she’s planning to sell at auction as part of a new push to simplify her life. “Being a director is probably the best job for me,” she says, “because I was a kid who always told her mother what to do. lt‘s the way I was brought up; my mother gave me so much power.” That's true enough—her mother was into role reversal before Barbra was into her teens—but it barely hints at the complex story of how she’s using that power now, how she has used it in the past, and how directing movies has become the governing passion of her life.

“I think I’m in a good place now,” she tells me, with only a tinge of tentativeness. “I think l’m putting things into proper perspective.” She talks of directing as liberation—a way to attain some of the personal freedom that has eluded her as a perfectionistic, sometimes reclusive, performer.

“One day, on The Prince of Tides, for instance, we’re shooting this chaotic traffic scene on Sullivan Street in Greenwich Village, except it isn’t chaotic enough ‘cause we haven't hired enough cars. So I walk down the street — which is great, because as Barbra Streisand the actress I would've been so shy, but now as Barbra Streisand the director I can use being known as an actress—so I walk over to some guy's car and go, ‘Hi, I’m Barbra Streisand; I’m directing a movie here. Would you mind being in the shot?’ And I go to one of the cops, ‘Hey, officer, would you do me a favor? I don’t have enough cars, and I’d love for them to back up. Would you mind?’ Or shooting in Grand Central Station and knowing I only had five hours a day for two days to shoot what people thought would take twenty hours or more. . . . Those were the hottest days, the most spontaneous. It was so much fun. It was so alive.”

She speaks of herself as a woman who wants other women to understand that they don’t have to act like men to be powerful. “Some magazine writer called Cis Corman to find out what kind of director I am and said, ‘Is she controlling or demanding?’ Well, what about nurturing and supportive? Why not try that? Because I am controlling and demanding. I think all good directors are and must be. I have an instinct, a vision, a truth barometer. I like the truth. I like small moments. I like real feelings, and I can hear the difference. But you don’t get good performances just by being controlling and demanding. I’m a woman. I’m a mother. I know that to get the best out of people, you have to be kind and gentle and nurturing and caring.”

Beneath the calm self-security, though, is a subtext of abiding hurt. For all her acclaim as a singer and actress, for all her wealth and power, Barbra Streisand still wants to be taken more seriously as a director than Hollywood has thus far been willing to take her.

Never mind that her work in Yentl made her a role model for young women in the movie industry. (“You can have all sorts of people tell you anything is possible,” says Jody Podolsky, a twenty-one-year-old film-school student at the University of Southern California. “You can even go to a Bible school and hear it from a rabbi. But it took Barbra Streisand’s impassioned delivery in Yentl to make me believe it.") Never mind that many directors considered Yentl a brilliantly crafted motion picture.

What infuriates Streisand are the stories, and there have been many, that dismiss her directorial work as that of a willful dabbler, and those portraying her as an obsessive control freak and nothing more. (When similar stories of control are told about male directors—Stanley Kubrick, for example—their obsessiveness is held up as a virtue.) What wounds her, to this day, is the snub she received when the Motion Picture Academy didn't deem her direction of Yentl worthy of an Oscar nomination. “I know, I know,” she tells me, “I shouldn’t keep harping on old hurts, but what can I tell you? The Prince of Tides is about being flawed, and I'm flawed too. I'm still on my journey, like everyone e se.”

I should disclose a special interest in Yentl, and a friendship with Streisand that goes almost thirty years, when she and her husband, Elliott Gould, moved into the twenty-first-floor penthouse of an apartment building in Manhattan where I was living—on the tenth floor—with my wife, Piper Laurie. One night, my extremely upstairs neighbor called to ask a favor. A man named Valentine Sherry had just brought her a short story that he thought would make a good movie. She wondered if I would read it and tell her what I thought.

The story was Isaac Bashevis Singer’s Yentl, the Yeshiva Boy. I read it immediately, was enchanted by it, and told her to grab it and make it her next movie. I’d like to be able to report that my neighbor, acting solely on the basis of my ineffable wisdom, did make Yentl her next movie. But that’s not quite how it worked, of course. The night she called me was over twenty-two years ago, and I was only the first of countless people whose advice and support she solicited on Yentl’s long, notoriously difficult journey to the screen.

I should also say that I've seen Streisand’s strangle-hold on details up close, and it can be eerie, to say the least. When she was putting the finishing touches on the sound track for Yentl, she came into a recording studio in West Los Angeles one night to rerecord a single phrase on one cut. Everyone was ready to go: her topflight producer, Phil Ramone, plus a couple of equally impressive engineers. When they played the offending phrase in Streisand’s headphones, she said no, that was the wrong take. When they assured her it was the right one, she assured them it wasn’t. When they said the computerized system didn't lie and the only remote possibility of error was a computer glitch, she asked them to summon the computer maven posthaste. This conversation couldn’t have been friendlier or more respectful on either side; top people love the challenge of working with her—although it can be exhausting—and she loves working with them. Still, everyone in the booth assumed Streisand was wrong. Then, the computer maven arrived on his motorcycle, typed a brisk query to his trusty microchips, and discovered she was dead right.

Everyone who has ever crossed Barbra Streisand’s path has similar stories to tell, but the stories themselves are only microchips in the mosaic of her work, which shines with big, bold motifs as well as tiny details. If her camera in Yentl studied crystal and china and storks on chimneys, it also dramatized vivid issues of femininity, feminism, sexual identity. “I talk best through my work,” she tells me now, after a whole afternoon of earnest talk, “through the songs I sing and the pictures I decide to make.” When she found her Isaac Singer short story, I realized much later, she found a perfect container for her ambitions. Her decision to make Yentl connected deeply with the woman she was and wanted to be. Yentl was a Jew who wanted to break out of the shtetl, as Streisand had done, in her fashion, when she left Brooklyn. Yentl was a female who rejected the dim-witted dominance of males. Above all, Yentl was a self-taught scholar with a stubborn streak and a restless mind—voracious, devouring. That’s Barbra Streisand all the way.

In her new book, Movie Love, Pauline Kael notes that “there is so much to love in movies besides great moviemaking,” and quotes the young writer Chuck Wilson, whose earliest movie memory is of being taken by his mother and his aunt to see Funny Girl when he was six: “In the final scene, when Barbra Streisand, as Fanny Brice, sings ‘My Man,’ it seems to me that I grew taller, yes, I leaned forward, some part of me rose up to meet the force coming from the screen. . . I was rising to get close to the woman I saw there. But I also rose to get closer to my self.”

In a sense, Streisand was doing the same thing: trying to express a self that hadn’t come out yet, except in her interpretations of other people’s words and music. She was a force to be reckoned with, heaven knows, but the prodigious performer kept viewing the world around her through a director’s eye. “For so many years,” she recalls, “I’d sit there watching certain directors and wonder: ‘Why are they doing that? Why did they put the camera there instead of there? Why are they letting that actor get away with that performance when it could be so much better? Why are they just settling for less? And for so many years, if I expressed an opinion, I’d be out of line.”

She expressed endless opinions, to be sure—often to her directors’ dismay but sometimes to their delight. William Wyler, the distinguished director of Funny Girl, had one deaf ear, but he never turned it to her. On the last day of production, he presented her with an engraved megaphone, because he thought she should be a director too.

After the frustration that replaced the elation of directing Yentl, Streisand lacked another project for several years. Then, while she was making Nuts, the music editor mentioned The Prince of Tides as a story she ought to direct. Although she wasn’t familiar with the novel, Don Johnson, whom she was seeing at the time, was engrossed in The Prince of Tides too, and he read passages to her aloud. Slowly, like so many things in her life, her commitment to Pat Conroy‘s book took root. This time, the story was contemporary and more accessible than Yentl to mass audiences. Just like Yentl, though, The Prince of Tides had deep connections to Streisand’s life. It spoke of parents’ demons and children’s pain, of growth accelerated by psychotherapy into dramatic change, and all of this at a time when she was using therapies, both formal and informal, to make sense of her own losses and distress.

“The movie is not just about being flawed but about forgiving the flaws in yourself,” she says. “Because, when you can do that, you can forgive others. How many people love themselves? It has such a negative connotation.” Then, for a moment, the movie is forgotten. “My mother always used to say .. I’d say, ‘Ma, why didn’t you ever give me compliments?’ and she’d say, ‘I didn’t want you to have a swelled head.’ So a child grows up feeling very insecure . . . if they don’t have parents who gaze at them, just gaze. . . . When you’re a baby with parents who lovingly gaze at you, then you figure you’re worth being gazed at.”

So much goes unspoken here. How would Streisand’s life have turned out if loving gazes had greeted her every morning of her young life? Maybe marvelously well, maybe not fulfillingly at all. What she does say is that, three weeks into production of The Prince of Tides, her mother underwent coronary- bypass surgery, and suddenly, her perspective changed. “I remember feeling, once my mother survived her operation, that this was all such a gift. I mean, the movie was only a movie, but how lucky I was to have this opportunity to have my mother still alive, that that was the important thing—life.”

As a mother herself, Streisand took a big chance in casting her son, Jason, to play her character’s son, Bernard. She now goes to touching lengths to explain it wasn’t her idea—Pat Conroy put her up to it when he saw a picture of Jason on the piano in her New York City apartment—and that Jason himself wanted to play the part. “Jason has never asked me for anything. Jason is not ambitious. He doesn't have a big desire to be famous or anything like that, because, you know, it’s complicated being my son and Elliott’s son, problems of competition and all that. But here my kid calls me up one day and says, ‘Mom, about that role, I hear you’re getting ready to cast someone else, but what happened? I thought you thought I’d be good for it.’ ”

There was one problem—a pretty funny one, in retrospect—during a scene shot in Central Park. Objecting to one of Jason’s line readings, Streisand asked him to do it several times again. “Jason got mad,” his director recalls. “He said, ‘What’s wrong, you don't like it?’ I said, ‘Jason, you have to separate here. I’m saying everything you’re doing is wonderful, but I don’t believe this particular line reading, and I can’t lie to you, so let’s work on it, and don’t be mad at me as your goddamned mother.’ So he walks over to Cis Corman, and he goes, ‘My mother doesn't like my line reading,’ and his Auntie Cis goes, ‘Well, I like your reading,’ and he comes to me and goes, ‘Well, Cis likes my reading,’ and I go, ‘Yes, but Cis is not the director.’ ”

Aside from that Oedipal counterpart of a computer glitch, the professional relationship was untroubled and productive in the bargain; Jason Gould gives a skillful, winning performance. So do many others in the film — Blythe Danner, Kate Nelligan, George Carlin — for Streisand’s touch as a director is uniformly sure. Now the trick, in upcoming segments of her life, is for her to be as sure about herself. She wants that recognition as a fine director, but will she give proper credit to herself, whether or not she gets it from others?

“I don’t know,” she says slowly. “I have moments. I have moments when I look at things and go, ‘My God, I remember how tough it was to get that shot, but I got it.’ ” Then she ventures a cautious smile and picks up the pace again: “What I do know is that I’m tired of apologizing for who I am. I’m tired of defending my being difficult or whatever, because it's such nonsense. I am a person who’s in pursuit of excellence. I think I’m a good person and a kind person and a compassionate person, though I’m also impatient, because I do have a singleness of purpose, and anyone who doesn’t like it can lump it.”

END.