Kennedy Center Honors: Barbra Streisand

By Peter Marks

December 7, 2008

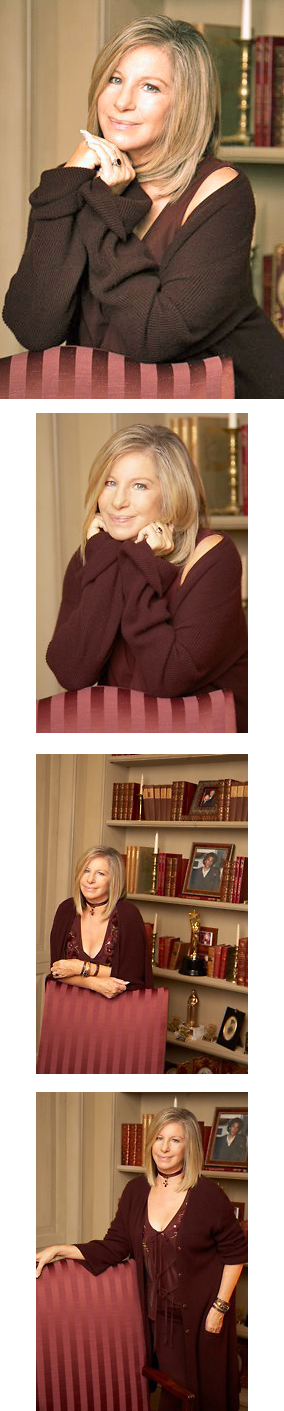

(Photos: Top photo originally ran with this story; all photos by Deborah Wald)

MALIBU, Calif. — The first building you encounter, driving into Barbra Streisand's oceanfront compound, is a henhouse. So who knew: chickens? They're penned in a prominent spot on her exquisite grounds, amid the drop-dead Pacific views and a collection of houses decorated so meticulously by the superstar that a visitor could hyperventilate from sheer overstimulation.

The landscape's mesmerizing impact even makes poultry look radiant. As you pass the rustically immaculate chicken enclosure, you're tempted to catch the eye of one of the birds and whisper: "Hello, gorgeous."

"Barbra gives some of the eggs to her neighbors," says her assistant Sara Recer as she conducts a tour of the gently sloping property, on which a chlorinated stream leading to a lap pool meanders past grassy embankments and manicured rose gardens.

Our destination is the newest addition to the compound, an amazing house overlooking the water that has been Streisand's consuming project for five years. She freely admits that it's a structure, a shrine of sorts, to her passion for early American design, to which she's devoted as much thought and time and energy as any work that brought her an Oscar or an Emmy or a Grammy. She says she's even written a script for the house that explains why she had "1790" carved into its stone silo, and why on another side of the house she has inscribed "1904." The year contains her lucky number, 4. It also happens to be the year in which her directorial debut film, "Yentl," was set.

"Oh, honey," Streisand says, when asked later whether the house had kept her up nights. "I used to have like a hundred notes every weekend, walking through. Then it came down to 75. A few years later, it was about 50, 35. But it's my work. Instead of directing a film, I directed the building of a house."

Atop this breathtaking promontory, where every vista looks as if it belongs in a movie, the 66-year-old Streisand wants you to understand what she has been up to the past few years, between occasional recording sessions and the rare big-screen appearance (in "Meet the Fockers"). She is sitting in a formal living room of her main house, a few steps from the recently finished showplace, which, with its handsome, automated screening room, she mainly uses for entertaining. She eagerly launches into a discussion of the new house's origins, how during summer driving trips up the East Coast, she stopped with a tape measure to record the dimensions of clapboard siding; how every interior reflects an influential architect at work in 1904, from Charles Rennie Mackintosh to Hector Guimard to the firm of Greene and Greene.

She catalogues other details, the sort you'd take in only if her homes formed the basis of your doctoral dissertation: "I don't know if you noticed, but outside of every house the flowers are only the colors of the rooms . . ."

The stories of Streisand's perfectionism — spun in the press at various times in her career as evidence of integrity, or insufferability — find traction in the intensity of her talk of brass and Stickley and moldings and black-to-gray and burgundy-to-rose.

"You see," she says, "it's an obsession. You know, a movie is an obsession when I'm doing it; the house became an obsession. I just didn't think it would take five years."

Whatever drives her obsessiveness, the fruits of Streisand's labors are undeniable, whether directed toward brick and mortar or vinyl and celluloid. She is, without a doubt, one of the greatest singers in history, a recording artist who has amassed 50 gold, 30 platinum and 18 multi-platinum albums, a magnitude of success second only to Elvis's. She's won Oscars in two categories: acting (for the 1968 "Funny Girl," in a famous tie with Katharine Hepburn) and songwriting (for "Evergreen," from the 1976 remake of "A Star Is Born"). She's directed movies of deeply personal significance (from the underrated "Yentl" to the underbaked "The Mirror Has Two Faces") — and, if you will, recast the idea of Hollywood beauty in her own image.

"People always talk about her as a perfectionist, but what does that mean?" asks her friend and longtime collaborator Marvin Hamlisch, who met her as a rehearsal pianist on "Funny Girl," the 1964 Broadway musical that launched her as a phenomenon.

When Hamlisch assembles the musicians for a Streisand tour, for example, he tells them that if they're not willing to bend the rules and work serious overtime, forget it: "If we're going to do this by the letter of the law, then don't do this," he instructs them. "I'm not going to stop if she is on a creative roll."

"Her talent is her voice and her unbelievable taste level," he adds. "Let's assume you were working for NASA and they're going to be putting a man on the moon. Everyone has to do a perfect job. What she is, is the vessel that can get you to the moon."

Tom Santopietro, whose 2006 book, "The Importance of Being Barbra," assesses Streisand's career highs (e.g., "The Broadway Album," 1985) as well as lows (the movie "For Pete's Sake," 1974), says our fascination with her has to do with that rapidly churning metabolism, that aspect of her drive that believes "the public deserved her best."

"The Barbra Streisand engine is: What's next?" says Santopietro, a longtime Broadway theater manager. "This incessant 'what's next,' it's always what's just over the horizon. That fuels the artistry."

A lack of belief in herself has never been an obstacle.

"Actor-singer-director-composer-producer-designer-activist" is how she is somewhat grandly introduced in her own handout biography. And now, all these hyphens are to be linked and acknowledged in a single evening, as she adds to her trophy shelves her Kennedy Center Honors medal.

"People say: 'You're getting the Kennedy honor? I thought you got this like 10 years ago,' " she says. It's true: The award is overdue. Politically, though, the timing is odd. When it's pointed out that she's accepting the award in the presence of President Bush, Streisand -- a liberal Democrat so high-octane that she asserts on her Web site that the past two presidential elections were "stolen" by the Republicans -- shifts a bit uncomfortably on her sofa.

"I would have loved to be there during Bill Clinton, of course," she says of the president she was closest to; she endorsed Hillary Clinton this year, before shifting to Barack Obama, after he became a numerical certainty for the nomination. Given the results of Nov. 4, Washington no longer has to feel like hostile territory. During a concert before a recent election — she's a reliable singer for Democrats' suppers — she tried to conjure a Democratic victory with a rendition of "Happy Days Are Here Again."

Now, for her, they finally are. "Such an incredible step forward for our country, against racism -- the good guy won," she says. So she'll willingly shake hands this weekend with Bush, be feted at the traditional State Department dinner by Condoleezza Rice -- the whole GOP-heavy shmear?

She grins. "Barack took the high road in this election," she says, "and I'm going to have to take it, too."

Streisand is a sharp-witted if less exuberant version of the passionate, iron-willed characters she created in her two most memorable movies, "Funny Girl" and "The Way We Were." (They aren't her only strong films: "Nuts," the play-based movie in which she's an angry prostitute accused of murder, and "What's Up, Doc?," in which she portrays a nutty perpetual student, show off her range, for drama as well as screwball comedy.) Wearing her hair in a sleek variation of that classic Streisand bob, she's a youthful 66. Svelter, too, than she looked in her turn as Ben Stiller's earthy Jewish mom in the 2004 "Fockers," the only movie she's been in since 1996's "The Mirror Has Two Faces."

Although she's allergic to celebrity duties, such as sitting for interviews -- "I never liked anything for publicity" -- she's forthcoming and down-to-earth. Despite a legendary reputation for wanting to dictate terms, especially on movie sets, she seems on this autumn late afternoon a model of compliance; after her assistants order her back into a chair for more photographs, she groans but obediently returns to the seat.

The only time she chafes is when a visitor mispronounces her name, making the common mistake of articulating the middle "s" in Streisand as a "z."

"Strei-sssssand! Soft 's'!" she admonishes, interrupting a question. "Like sand on a beach. Why do people call me 'Strei-zand'? How can I be famous? They don't say 'Judy Gar-LAND'! "

The trials of renown! For a woman who still inspires a frenetic variety of fan worship, particularly among older women and gay men, Streisand has a queasy relationship with wealth and fame. About the kinds of public triumphs others happily relive, she draws blanks. "Quincy Jones, my dear friend, said, 'Don't you remember . . . our first [Grammys] together in [1964]?' I said, 'Nope.' He sent me a picture."

Did that jog her memory? "Not really," she says. "I remember the dress, but I wore that dress a lot for singing -- a plain black dress from the thrift shop."

Streisand was 19 when she opened in her first Broadway show, "I Can Get It for You Wholesale," for which she earned a Tony nomination. Maybe when you are both famous and put up for prizes your entire adult life, image maintenance becomes a bore. Asked whether her outspoken politics might have touched any raw public nerves over the years, she replies: "I don't think about that stuff. Did people stop buying my records? Maybe. But that doesn't matter to me. I don't care."

She turns down a lot of awards, especially when they require her to speak. A 1995 address at Harvard, where she was invited to talk about the artist as citizen, made her a complete wreck: "I was rewriting as I was walking up to the podium." Years ago, she declined an offer for that flashbulbpopping emblem of Tinseltown, a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

"I refused it because I thought it was so hokey. . . . It's like to me, always the work should speak for itself. And nobody agrees, they have to force me. And guess what? You know when I got the star? When my husband got it!"

Her husband is actor James Brolin, whom she married a decade ago, and who at this moment is sprawled on a couch in a family room down the hall, watching a video. A picture of her son, Jason Gould, who acted with her in "The Prince of Tides," sits on a living room table. And somewhere else in the house, Streisand's little white dog, Sammie, a 5-year-old coton de Tulear, a breed from Madagascar, can be heard padding about.

Brolin figures, to some degree, in the issue of why her movie career has all but ceased. She says she does want to direct another film, citing "The Normal Heart," the prescient AIDS play by Larry Kramer that has been on and off her To Do list for something like 15 years. But she wonders how the all-consuming task of making a movie would affect her relationship with Brolin.

"I've never really been, you know, married during a directorial time in my life," she observes. "How do you, you know, balance the personal?"

Of all those aforementioned career hyphens it is directing that she loves best, though some of her fans might want her to say it's the voice that matters to her most. In 40-plus years of recordings, she has sold 71 million albums; she has just started work on a new one, with the singer Diana Krall. No theme, she avers, "just songs that I like." (A DVD of the 1983 "Yentl" is also due for release early next year, she says.)

"The voice is the best present God gave her and the world," says Hamlisch, who wrote the music for one of her greatest hits, "The Way We Were."

"I heard her the first time on TV, on a talk show. She would come on the show because the host had seen her at the Bon Soir," a New York nightclub. "She sang 'A Sleepin' Bee' with a piano player, and you just went nuts. You went, 'Oh, my God.' "

Alan and Marilyn Bergman, who among their many other pop hits wrote the lyrics for "The Way We Were," recall hearing Streisand try out the song, alone in a room, and making some suggestions about the lyrics and music. "Which we took, because they were correct," Marilyn Bergman says.

"Always substance is ahead of style," Alan Bergman remarks. Marilyn adds: "She has to understand and identify with what she's singing. She had to get it at one level or another. If not, she would question it."

Still, no process engages Streisand quite like what happens when she's in the director's chair: "It just encompasses everything you are, everything you know, everything you've learned, all your instincts, feelings, psychoanalysis, dealing with actors, getting the best out of them." It's inspiring; you're filming something, then all of a sudden you see something, you can say, 'Turn the camera and get that, pick it up.' "

What she describes surely is an extension of what she's been doing on sets ever since she got out here, and in those early years she paid a price for daring to open her mouth: "When I first came to Hollywood, the fact that I had opinions?" she says, rolling her eyes. On "Funny Girl," she, director William Wyler and cinematographer Harry Stradling all "adored each other, but all of a sudden, you'd read about: She's telling the cinematographer what to do!"

"It's just that I had an opinion! 'What do you think if, you know, we did a shot from there, or we put this in the script?' . . . But I guess I was coming from an era when women didn't do that."

To those who've studied her work, the fact that directing would come to be the primary passion makes eminent sense. "Of course!" Santopietro says. "She's creating her own universe."

Which, in a way, is also what's occurring in her Malibu idyll. "I love Eastern architecture, Federal and Colonial architecture," Streisand says. "But I don't want to live in the East, so I brought the East to the West."

Strolling from room to room her assistant in the new house, you're on overload by the time you descend the circular staircase to the basement, which Streisand has turned into a period village streetscape, with little antiques and sweet shops. One "shop" is filled with female mannequins behind glasswearing Streisand's costumes from various movies. In the closets are more costumes, arranged by color.

To record it all, you'd need a full afternoon. "I don't know if she pointed these things out to you," Streisand says later, "but most of the doors are different on two sides. So when you're in a pine room, you're coming from pine wood, old pine floors, you know, doors and it's a honey color. You go into Mackintosh, the other side, the wood changes to oak from pine, the color of the stain gets darker, the hardware gets simpler and darker, not brass like on the pine -- see what I mean?"

Asked whether she'd like to design something like this for someone else, Streisand looks stricken.

"God, no," she says.

The Kennedy Center Honors should be a pleasant distraction. "It's nice, I like it, because I love America," she says of the recognition. "It's an American tradition. I loved President Kennedy. I sang for him." A photo on a desk in her study depicts the young Streisand gazing at JFK as he signs an autograph.

"And the White House is architecturally so amazing. I actually, in my New York apartment, copied the second-floor draperies. But I had a better color yellow on the walls."

End.

[ top of page ]